Rochester is a great place for a day out. It has everything; easy access (40 minutes from London by train), plenty to see and do, and good places to eat. And, as you can see, it’s certainly picturesque.

Tudor Timber-framed Houses in the High Street

Rochester has always been a place of strategic significance, being linked to the Thames estuary by the River Medway, and, since Tudor times it’s been important for the navy. The 17th century diarist, Samuel Pepys, whose career started as a ‘clerk of the King’s ships’, constantly visited Rochester and the other Medway towns. Later, he rose to become Surveyor of the Victualling Office, where he battled against entrenched abuses of the system, eventually creating a modern navy, equipped to deal with the formidable Dutch navy.

The 1856 bridge over the Medway. Note the lions guarding it on either side, not to mention the Roman pedimented portals. The Victorians loved making statements about their importance.

In pre-Roman times, there was a ford here. The Romans built the first bridge across the Medway and a small settlement called Durobrivae grew up as a staging post on Watling Street, the Roman road which went from London to Dover.

Remains of Rochester Town Walls

Rochester still has some of its old town walls. The photo above shows the neat, square Roman stones (Reticulatum) in the bulge to the right, the more bumpy Medieval stone wall is on the left and an 18th century red brick garden wall runs along the top. It’s an amazing survival.

Rochester’s history springs from its location. It was almost always the first port of call for invaders from the continent. As we have seen, the Romans landed nearby; in the 5th century, the Jutes, Hengist and Horsa, invaded England via the Thames and founded the Kingdom of Kent; St Augustine arrived in 604 AD and made Rochester into a bishopric. The town gradually rooted itself and prospered.

Rochester Castle

Rochester Castle, which towers over the town, was mentioned in Domesday Book (1084), though, at that date, it was only a timber and earthwork structure. Later, in the 12th century, a stone castle was built by Gandulf, Bishop of Rochester, and held for the king. In 1215, King John laid siege to the Castle – it was being held by disaffected rebels – and, succeeded in destroying the north-east corner of the keep. Starvation forced the rebels’ surrender. Later in the 13th century, Simon de Montfort tried – and failed – to take it.

Rochester Castle plus cannon

Perhaps Rochester was just too close to London to have had a quiet history. In the 12th-15th centuries, England laid claim to large chunks of France, and Rochester was en route for English armies either going to France or returning. But history moves on, and by 1610, the castle had become surplus to requirements. It was gutted and large portions of it were dismantled but the square 120 ft keep still stands and is the highest in England – the views from the top are spectacular.

Rochester Cathedral (Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia)

The cathedral is basically Norman but has been much rebuilt over the centuries, ending in Sir George Gilbert Scott’s major restoration of 1871-77. Rochester is very proud of its cathedral. Charles Dickens, who grew up in nearby Chatham, and died at his Gad’s Hill Place home a few miles outside the town, wanted to be buried there but the powers that be decided otherwise, and he now lies in Westminster Abbey.

Leaning house in High Street

However, Rochester has many other interesting buildings. I particularly like the leaning house above. It may look as though it’s my photography which is at fault but I assure you that it’s not so. The house really is at that angle. I can’t help wondering what the floors are like inside; I hope they are horizontal, otherwise it must be like being on board ship before stabilizers were invented.

The Corn Exchange

This impressive building was built in 1706 by Sir Cloudsley Shovel (1650-1707) and donated to the town of Rochester. It is also known at the Clock House, for obvious reasons. Sir Cloudsley was a renowned 17th century naval hero who fought Barbary pirates, engaged in numerous sea-battles with the French, helped to capture Gibraltar, became Admiral and Commander of the Fleet and died tragically when his ships were wrecked on Bishop and Clerk rocks off the Scilly Isles. It was this loss which spurred the Navy into offering a large monetary prize to anyone who could find a reliable way to measure longitude on board ship.

Charles Dickens’ Swiss Chalet

This is the Swiss Chalet given to the author Charles Dickens as a writing retreat. It was originally in the garden at Gads Hill Place, just outside Rochester. Nowadays, it has a home in the garden of Eastgate House, a place Dickens rightly called ‘a venerable brick edifice’, and the 17th century town house of Sir Peter Buck, a senior officer at the Royal Tudor Dockyard. It is a grade I listed building and open to the public.

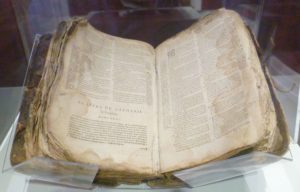

Huguenot Museum: The Fasquet family Bible (1588-90), smuggled out of France by being baked inside a loaf of bread. The title page was torn out to protect the family’s anonymity. Once safely in England, the Fasquets recorded family births, marriages and deaths until 1625.

I hadn’t realized how strong the Huguenot presence was historically in Rochester until I visited the Huguenot Museum. In the mid-16th century in France, there was constant war between the French Protestants, known as Huguenots, and the Roman Catholic Church. Things came to a head with the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre on 24th August, 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed. Many Huguenot families fled to the nearby Protestant Germanic states, Switzerland and Britain. And, just as earlier invaders had done, they, too, came up the Thames estuary and landed in Rochester. They were known for their skilled craftsmen, particularly in the silk-weaving business, and this, unexpectedly, impacted on the French economy.

An example of Huguenot silk-weaving; many silk weavers settled in Spitalfields in London

Fashion was, naturellement, of supreme importance to the French and something had to be done. In 1578, the Edict of Nantes allowed Protestants freedom of worship, which stemmed the flow of emigrants for about a hundred years. But in 1685, the Edict of Nantes was revoked and, once more, Huguenots fled, this time in larger numbers.

Examples of the silversmiths’ art

Paul de Lamerie is probably England’s best known silversmith of Huguenot descent. His parents fled France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes and came to England in 1691. He, and thousands like him, brought their skills in finance, industry, silk-weaving, gold and silver-smithery, and skilled cabinet making, all of which gave a huge boost to their new country’s economy.

Sidney Lewis’s family cabinet-making tools. They were used after World War II to carve woodwork in the House of Commons after the Blitz had damaged the building. Sidney was the sixth-generation of cabinet-makers, descendants of a Huguenot emigrant family.

With the influx of Huguenot furniture-makers, the style of furniture changed. Square Tudor oak furniture fell out of fashion, and in came the carved shapes and rich veneers the French favoured.

The Huguenot Museum is on the upper floor of the Tourist Office and is a fascinating look at this largely unknown history. I particularly enjoyed the film clips of various descendants of Huguenot immigrants telling their family stories. One in six people in Britain may be descended from Huguenots. My family comes for the North-East, so I doubt if I’m one of them; on the other hand, I know several people who are. (Jane Austen fans might like to know that Tom Lefroy, with whom Jane enjoyed an all too brief affaire du coeur, was of Huguenot descent.)

The French Hospital Almshouses were founded in 1717 to support Huguenots in need

The French Hospital is not usually open to the public, though there are a few guided tours during the summer months.

The Esplanade Gardens

I’m ending with the Esplanade Gardens, viewed from the entrance to the castle grounds. The Medway was once full of ship-building, with warehouses for various items which victualled the ships but, nowadays, it is a public park with bright summer bedding and pleasure boats moored along the river. You can take a boat trip or simply enjoy the view. There are plenty of things to choose from in this lively town.

All photographs by Elizabeth Hawksley unless otherwise stated.

www.huguenotmuseum.org www.visitmedway.org

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

What an amazing place! I love that castle. And the Huguenot Museum sounds amazing. A horrible day for them St Bartholomew’s. Fascinated by the Spitalfields silk connection. Had no idea about that. Lovely post.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. What I particularly like abut Rochester is the sheer variety of what there is to see. And I scarcely mentioned the pubs and eateries, or the shopping, not to mention Baggins Book Shop, the biggest second hand bookshop in England!

I meant to say we have a whole high street of Tudor buildings in my town East Grinstead. They are very like this one but not as grand.