Illuminating the Dark Ages is no easy task, as I discovered when I went to the British Library’s new Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War exhibition. There are a lot of illuminated manuscripts, most of them beautiful, but what, exactly can they tells us about that troubled period? A surprising amount, as it happens.

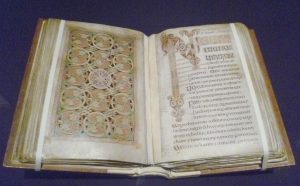

The Lindisfarne Gospels, one of the glories of Anglo-Saxon craftsmenship. This illuminated manuscript was produced in the monastery on Lindisfarne in 715-720 AD. Its sophisticated designs owe much to Celtic art.

When the Roman legions left England in 410 A.D., they left the field open for the arrival of Angles, Saxons and Jutes in the south-east, and Picts from north of Hadrian’s wall. These newcomers were, at least initially, raiding war-bands, relying on a strong leader; they arrived, pillaged and left with their booty. Later, they returned to settle. The Romans had left an excellent road network which was, doubtless, welcomed by the invaders, but also many splendid public buildings, which, almost overnight, became redundant. The newcomers didn’t do cities; they didn’t know about sanitation and drains; and nor did they do bureaucracy, and they were largely illiterate – though they did have runes, of which more in a moment.

Whalebone writing tablet and stylus, late 8th century. Parchment was very expensive, so scribes would have learnt to write using a writing tablet covered in wax

Under the Romans, ordinary Britons had not been part of the ruling, administrative class. Rome ruled from the top; it was the Roman governor who ordered a legion to go wherever it was needed, and sent letters efficiently from Londinium to those in command in Eboracum (York), Deva (Chester), Lindum (Lincoln), Portus Dubris (Dover) and elsewhere. The ordinary Britons who remained once the legions had left had no organizational skills to enable them to defend Britannia. They were left vulnerable to foreign attack – which came swiftly.

Late 8th century runic charm? The silver-gilt creature, probably from Mercia, has blue glass eyes, scrolled ears, fangs and a hooped tongue. The runes engraved on it are unclear.

The Scandinavian and Germanic invaders, as I said, had runes, a script of twenty-four angular letters, usually carved on wood or cut in stone. Runes were seen as having magical properties and were used mainly on monuments or to record charms or curses. Interestingly, for several hundred years they were used alongside the Roman alphabet as we can see from the object above.

By the end of the 5th century, the Jutish king, Hengist, had settled in Kent, with other Germanic war-lords settling in Sussex and Wessex, where they eventually integrated with the indigenous British. Britannia, no longer a Roman province, had fragmented along old tribal lines or into small Anglo-Saxon ‘kingdoms’.

However, though the Danish immigrants may have been largely illiterate, they had top quality metalwork skills and a strong oral literary tradition, as in Beowulf, the Old English tale of the Beowulf, the Geatish hero’s slaying of the monster Grendel, and Grendel’s even more ferocious mother.

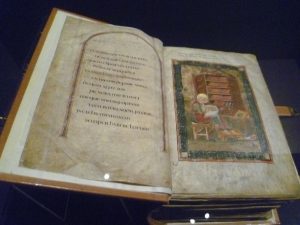

The Book of Durrow, mid-8th century, Ireland

However, there was one group of people in Britannia who did have organizational skills and who were literate, and that was the Church. Christian monks from Ireland had arrived in Iona on the west coast of Scotland in the 5th and 6th centuries AD and, eventually, reached Northumbria. The Celtic church had close ties with Rome, and the mid-8th century Book of Durrow was the earliest fully-decorated gospel book to arrive in England from Ireland. The monasteries set up by the Northumbrian monks became famous for their learning and they, too, corresponded with the wider church in Europe and Rome.

However, Christianity also arrived in Britain quite separately, via Kent. The story goes that Pope Gregory saw some fair-haired children in the slave market in Rome and asked where they came from. When told that they were Angles, he famously remarked, ‘Non Angli, sed angeli’ (Not Angles but angels.) ‘It is well, for they have the faces of angels, and such should be the co-heirs of the angels of heaven.’ He ordered Augustine, one of his monks, to go to England and convert them. Augustine landed in Kent in 597 and was cautiously received by King Ethelbert of Kent. Fortunately, Ethelbert’s wife, Bertha, was already a Christian and the English were gradually converted – forging their own strong links with Rome and Europe.

Sutton Hoo gold belt buckle, early 7th century

The decoration of the Sutton Hoo (c. 627 AD) ship burial gold belt buckle has much in common with the decoration on the Irish Book of Durrow. The buckle is, actually, a hinged box with a triple-lock mechanism, designed to be worn centrally on the wearer’s body. The intricate workmanship depicts seventeen snakes, predatory birds, and various long-limbed beasts. I once went to a lecture where a slide of a similar intricate Celtic design was lit in various colours which showed how they all intertwined – so I know it’s true.

A page from the massive Codex Amiatinus. (It takes two people to carry it.) It has not been seen in England for 1300 years.

The art of writing with the sophisticated Roman alphabet was confined mainly to the church, and gifts of beautifully illustrated and decorated books were sent across Europe as valuable gifts. One of these was the weighty Codex Amiatinus, the earliest complete Bible in Latin made at the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow and taken to Italy in 716 AD by Abbot Ceolfrith, who had commissioned it as a gift to the Pope. The decoration above shows strong Mediterranean influence. Its English origins were only re-discovered in the late 19th century; before that, it was thought to have been Italian.

The ‘Don’t steal me’ brooch.

By the early 11th century, writing in the vernacular was being used outside the church. The example above is a silver-gilt brooch belonging to a woman with a verse inscription on the back in Old English. It says, ‘Ǽdwen owns me, may the Lord own her. May the Lord curse him who takes me from her, unless she gives it to me of her own free will.’ Curses were often used in wills and charters as a way of protecting property. a couple of hundred years earlier, it would probably have been written in the runic alphabet.

St Cuthbert’s Gospel, early 8th century, part of Northumbria’s ‘Golden Age’.

Gradually, the warring tribes and small kingdoms coalesced into three larger kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex. By 660 AD, Northumbria was the most powerful and, after Christianity arrived from Ireland, the quality of their illuminated manuscripts became famous throughout Europe; Northumbrian kings had strong links with Ireland, Northern Europe and Rome.

The Lichfield Angel, representing the archangel Gabriel, was discovered under the nave of Lichfield Cathedral and was possibly part of the coffin-shrine of Chad, 5th bishop of Mercia who died in 672 AD

Mercia eventually displaced Northumbria and, by the mid-8th century, King Offa of Mercia ruled Kent, East Anglia, Essex and Sussex – and controlled London. He created an important archdiocese in Lichfield, at the heart of his kingdom which is where the Lichfield angel, dated to about 800 AD, was found. But, by the end of the 8th century, England had once again become a desirable target for Danish Vikings and their raids increased in scale and ferocity; they smashed into Northumbria and then Mercia.

But it was the rise of the West Saxons under King Alfred and his heirs which eventually led to the dominance of the Kingdom of Wessex and justified Alfred calling himself King of England. The peace treaty between Guthrum, the Danish leader in East Anglia, and King Alfred of the Anglo-Saxons in Wessex in c. 880 AD, established the legitimacy of the Danelaw, the Danish kingdom which included Northumbria and Mercia.

The Alfred jewel, found a few miles from his fortress at Athelney in Somerset. It is an aestrel, a book pointer. It is inscribed ‘+ ǼLFRED MEC HAHT GEWYRCAN’. That is, ‘Alfred caused me to be made’.

Alfred (840-901 AD), significantly the only English king to have been called ‘the Great’, was more than just an effective war-leader, he created a new sort of kingdom, one which promoted culture as part of the proper observance of Christianity which he saw as vital, if he were to get God on his side. He patronized the arts, invited the best scholars to Wessex; and promoted the English language as fully worthy of being considered equal to Latin, the language of the church. He had various books, including Boethius’s Consolations of Philosophy, translated into Old English, so that all might read it, and he established schools.

He is also credited with organizing England into hundreds and shires so that they might be more efficiently governed; in other words, he established a workable political infrastructure for the first time since the Romans left over four hundred years before.

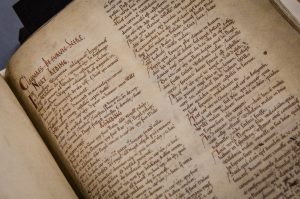

Domesday book, William the Conqueror’s detailed 1085-6 survey of his new country, a record of who owned what (land, mills, animals, and serfs) and how much they were worth, gives us a snapshot of England immediately before and twenty years after the Norman conquest.

Alfred and his heirs had created exactly the sort of country an ambitious man with an eye to the future might think worth invading. And it found one in William the Conqueror, a man with Viking ancestry himself, who invaded England, successfully, in 1066.

If you want to sum up what the Dark Ages did for us, Dr Claire Breay, the lead curator of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War exhibition put it very neatly: the Anglo-Saxons gave us the English Language. Its collision with Norman-French resulted in it losing its genders and inflected endings and what emerged was something infinitely more adaptable and with a much larger vocabulary which could express new linguistic nuances, and, eventually, become a world language.

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is on at the British Library until 19th February, 2019.

Photos: St Cuthbert’s Gospel, the Lichfield Angel, the Alfred jewel, and Domesday Book, courtesy of the British Library. All other photos by Elizabeth Hawksley.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Wow. This is a whole history lesson. I only learned a smattering of this stuff and most of it bit by bit. Fascinating that we got English from this period. All I knew of Alfred, to be honest, is that he burnt the cakes – and I got that from 1066 and All That! Incidentally, a book I loved.

I agree about ‘1066 and All That’ – I thought seriously about quoting the bit about the Danish invader ‘Hengist and his wife (or horse) Horsa’ but decided that the history was quite complicated enough without my adding to it!

This post took me hours – I only hope I’ve got it right. I shall email the British Library press office with the link tomorrow in some trepidation.

This is a period of history I don’t know how about, but I think its metalwork is beautiful I remember that Michael Wood series too …. and his tight jeans! Actually, I became a fan and loved his series on the Trojan War. It was a real thrill to meet him a few years ago. He gave a talk about the campaigns of Alexander the Great that I was fortunate enough to be invited to attend and he was a really good speaker. Very nice chap and easy to talk to as well.

How nice to hear from another Michael Wood fan. If you heard the talk about Alexander the Great at the British Museum, I was there, too. I also spoke to him afterwards – he has a voice like warm honey, and he signed my copy of ‘In Search of the Trojan War’.

Actually, it was at a talk he gave to the Macedonian Society at their headquarters in London. Quite a small group and then he stayed on for wine and canapes so there was quite a bit of time for chatting. The content of his talk might have been similar though, it was about the campaigns in Persia presented it with a very good slideshow….. oh yes, and I agree about his voice!

Lucky you, Gail!

I did Anglo-Saxon at uni, and love the period, but didn’t know that people cursed things specifically against theft, exactly as the Romans did. My mum had a thesaurus in her writing study, which had a curse in it on ‘whoever steals this book’ – obviously she believed in the power of such curses! Jane x

Thank you for your comment, Jane. I came across a bookshop which had a curse against theft notice on the wall- it was a shop which sold religious books, too! Apparently, the curse worked, because several stolen books reappeared!