In the early 19th century, every house of consequence had a shrubbery. Sometimes it was a simple grassy area with shrubs and a few trees; sometimes there was an attractive bench beside a winding gravel path where a young lady could sit and enjoy nature; and it could be as large or small as the owner wanted. In essence, it was the antithesis of the more formal parterres, geometrical shapes and clipped box hedges at the front of the house which proclaimed the owner’s status and control over Nature.

Formal gardens proclaimed the owner’s status

Behind the house and beyond the ordered flower garden and the walled kitchen garden, the owner often had a carefully controlled wildness. This, after all, was the Age of Sensibility, the Romantic Age, you needed a space where you could, metaphorically speaking, loosen your corsets.

Cupid in the pond; Love in the shrubbery?

In Jane Austen’s novels this wild space is usually called a shrubbery or a wilderness. In Mansfield Park, the wild space at Sotherton Court – the home of Maria Bertram’s fiancé – is called the wilderness – a name which is psychologically accurate, as we can see during Fanny and the Bertrams’ visit there. A lot of ‘wild’, primitive emotions, including resentment, lust, greed and jealousy, are unleashed here.

‘A nice little wood.’

Mary Crawford, Edmund Bertram and Fanny, the book’s heroine, peel off from the others and set out to explore. ‘Here is a nice little wood, if one can but get into it!’ Mary cries.… The door, however, proved not to be locked, and they were all agreed in turning joyfully through it, and leaving the unmitigated glare of day behind. A considerable flight of steps landed them in the wilderness, which was a planted wood of about two acres, and though chiefly of larch and laurel, and beech cut down … was darkness and shade, and natural beauty…’

There is a touch of the biblical Garden of Eden in Jane Austen’s description of the Southerton Court wilderness – complete with serpent. Here the attractive but self-centred Mary Crawford tries to persuade Edmund Bertram into giving up the idea of taking Holy Orders. Fanny, who is not strong, says, ‘I wonder that I should be tired with only walking in this sweet wood; but the next time we come to a seat, if it is not disagreeable to you, I should be glad to sit down for a little while.’

‘My dear Fanny, cried Edmund, immediately drawing her arm within his, ‘how thoughtless I have been. I hope you are not very tired. Perhaps, turning to Miss Crawford, my other companion may do me the honour of taking an arm.’ The serpent raises its head.

‘Thank you, but I am not at all tired.’ She took it, however, as she spoke, and the gratification of having her do so, of feeling such a connection for the first time, made him a little forgetful of Fanny.

Ah, that first magic touch! Who says that Jane Austen doesn’t do sex?

They soon find a bench. Well sheltered and shaded, and looking over a ha-ha into the park, was a comfortable-sized bench on which they all sat down. Eventually, Mary urges Edmund to move on. Fanny said she was rested, and would have moved on too, but this was not suffered. Edmund urged her remaining where she was with an earnestness which she could not resist, and she was left on the bench to think with pleasure of her cousin’s care. Edmund and Mary leave and are soon out of sight and hearing.

The serpent has successfully tempted Edmund into a prolonged tête-à-tête with Mary, and poor Fanny is been left alone. The wilderness can also be described as a place where people’s true natures are shown up, and we note that Edmund comes across as pretty inexperienced with regard to women. Yes, he’s concerned about Fanny but, underneath, he wants to be alone with Mary – which is something he is not allowing himself to see – and it is Fanny who pays the price.

About half an hour later, Mr Rushworth, Maria Bertram and Henry Crawford appear at the bench and they commiserate with Fanny. Maria is desperate to off-load her cloddish fiancé, Mr Rushworth. She’d much rather spend the afternoon in the wilderness with the much more attractive Henry Crawford. Eventually she manages to persuade Mr Rushworth to fetch the iron gate key into the park. Once he’s gone, she grabs the opportunity of having a tête-à-tête with Henry, and soon they, too, abandon Fanny. Once more, she’s alone.

Then Julia, Maria’s sister, appears, hot and cross. She is also in love with Henry and furious that Maria – who, after all, is engaged to Mr Rushworth – has disappeared with Henry. Fanny urges her to wait for Mr Rushworth, who will soon be returning with the key.

Julia refuses. ‘I have had enough of the family for one morning. I have but this moment escaped from his horrible mother. Such a penance as I have been enduring, while you were sitting here so composed and so happy … but you always contrive to keep out of these scrapes.’ And she too goes.

When Mary and Edmund eventually return, it’s obvious that ‘they were not aware of the length of their absence.’ And they had actually been to ‘that portion of the park into the very avenue which Fanny had been hoping the whole morning to reach at last.’ Fanny is left feeling disappointed and depressed.

Meanwhile, Mrs Norris is scrounging pheasant’s eggs, a cream cheese and a ‘beautiful little heath’ (heather).

Nobody, apart from Fanny, behaves well.

The whole scene is perceptively and subtly written and, once you’ve attuned your ears to Jane Austen’s frequency, it’s not difficult to pick up the sexual undertones.

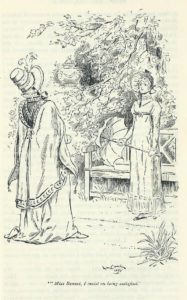

The shrubbery has another role to play; it is also a place where one can be alone, or, if with someone, not be overheard. Take Pride and Prejudice: even a modest country house like Longbourn had a fair number of servants. During the planning of the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, research revealed that a house like Longbourn would have had eleven servants. With that number, it must have been well-nigh impossible to be alone indoors. Lady Catherine de Bourgh knows this, and when she visits Longbourn to forbid Elizabeth’s possible marriage with Darcy, she insists on talking to her in the ‘prettyish kind of a little wilderness’ she spots rather than indoors where what she has to say may be overheard.

‘Miss Bennet, I insist on being satisfied.’ Charles E. Brock’s illustration for Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s visit to Longbourn. Note the bench, and the Classical urn in the background.

Elizabeth leads Lady Catherine along ‘the gravel walk that led to the copse’. Lady Catherine informs Elizabeth that her ‘character has ever been celebrated for its sincerity and frankness’, and lets rip her outrage and resentment at the very idea of Elizabeth ever being engaged to Mr Darcy – something she is determined to thwart. Again, the wilderness allows the expression of unrestrained emotion which Lady Catherine could not express indoors.

The Longbourn ‘wilderness’ is the only place where Lady Catherine can give full rein to her disdain of Elizabeth’s inferior class. She has no compunction in telling her that she will be censured, slighted and despised by everyone if she marries Darcy. Elizabeth, too, takes advantage of the wilderness to express her own feelings: ‘’You can now have nothing further to say,’ she resentfully answered. ‘You have insulted me in every possible method.’

The shrubbery at Hartfield in Emma fulfil a slightly different function – but it is still a repository for emotion. Here, the shrubbery is a safe haven, as we see when, after the episode where the gypsies harass Harriet, Mr Woodhouse makes Emma promise ‘never to go beyond the shrubbery again.’ And after the conversation where Harriet reveals her hopes that Mr Knightley might be in love with her and want to marry her, Emma simply doesn’t know what to do. ‘She sat still, she walked about, she tried her own room, she tried the shrubbery…’ But, this time, even the shrubbery fails to contain her tumultuous feelings.

‘He stopped to look the question.’ Hugh Thomson.

But the shrubbery can also be a place where harmony is restored and where love is offered, expressed and returned. After a stormy night, both real and psychological, it was summer again, and Emma loses no time in ‘hurrying to the shrubbery’. Here Mr Knightly finds her. Their emotions go from agitation, doubt, jealousy and discouragement to ‘the same precious certainty of being beloved.’ And who, on this earth, can ask for more?

All photos by Elizabeth Hawksley

An earlier version of this post was first shown in Libertà: https://libertabooks.com. My thanks to Sophie Weston and Joanna Maitland for inviting me.

Twitter: @Hawksley_E

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Thoroughly satisfying – what a good read. It’s a pity that most of us lack a shrubbery for when our emotions threaten to overcome us – we could all probably do with one!

Reading the passage about Edmund naively and happily abandoning Fanny, I found myself thinking, “Honestly – MEN!!!”

I loved your comment, Prem, it made me laugh – and I so agree with your sentiments. I’m sure other readers will enjoy it, too.

Part of the reason I chose to write a Jane Austen post this week, was to cheer people up. We’re going through a tough time and anything which makes people smile is, surely, a Good Thing!

What a fabulous book detective you are, Elizabeth! You would be a fantastic English Literature teacher. Your ability to note these things is amazing to me. And then I realise how right you are. I took them in on a subliminal level so that when you point them out, they become obvious. Thank you for this, and for your other detecting posts – both books and pictures, not to mention museum pieces. I think that’s why I love coming back for more. I always learn something new from you.

Thank you, Elizabeth, how kind of you. A couple of weeks ago, the stats on my post ‘In the Footsteps of St Patrick’ slumped. I thought, what’s happening? OK, most people may not be very interested in St Patrick but there are Holy Wells, Holy Springs, riotous Midsummer festivals which had to be suppressed, and some good photos – what’s not to like?

My first thought was to stop doing blogs – at least for the moment during the present crisis. However, later, I had second thoughts. What people want just now, I decided, was something cheering – and I suspected that Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen posts would fit the bill. And so it proved – my stats recovered. I’ve always enjoyed analysing books. I used to teach English Language and Literature to adults in a one year crash A level course evening class at a College of Further Education. I’m happy to report that they usually did very well.

However, I shall continue to vary the subject matter of my posts. I love both GH and JA but I am well aware that not all my readers share my tastes!

What a great read; so many good points. Finding the right setting is so important for writing emotional scenes and developing characters…

Thank you, Samantha, for joining the conversation and welcome to my blog. I agree with you about the importance of finding the right setting to convey characters’ emotions and to show your characters’ development. I think the ‘wilderness’ scenes in ‘Mansfield Park’ do this excellently – particularly with regard to Edmund. He’s like am innocent fly trapped by a particularly clever spider.

And the scene with Henry Crawford and Maria Bertram shows both Maria trying to find a way to reel Henry in, and his adroit evasions whilst simultaneously encouraging her. It makes for a gripping but uncomfortable read.

I am not very familiar with the works of Jane Austen, though I was forced to read Pride and Prejudice in high school.

On reflection, it seems obvious that a Shrubbery or Wilderness would be a good place for people to behave a little more wildy. As you rightfully point out, you can hide from prying eyes and escape from curious ears.

I wonder if people behave differently in a planned garden as opposed to a shrubbery? Perhaps some clever sociologist could be some research.

Thank you for your thought provoking writing.

Thank you for you comment, Huon. I’m really sorry that you were forced to read ‘Pride and Prejudice’ at school. A great mistake, in my opinion, especially for boys. Teenage boys cannot be expected to understand irony; why should they? They don’t yet have the experience of life to understand how irony can neatly turn any statement upside down to mean something quite different from what it says on the surface.

The famous opening of ‘Pride and Prejudice’, ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man, in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife’, means, of course, exactly the opposite. Most rich young men, being tied down with a wife is the very last thing they want! So, in the very first sentence, the reader is primed not to take the statement at face value and to realize that, whilst Mrs Bennet, with five daughters to dispose of, it may be crucial; for the men she has her eye on, it is a very different matter. And we can sit back and enjoy the ensuing comedy.

You might, one day, consider giving it another chance, and enjoy it as an adult.

What a lovely interesting post Elizabeth. Thank you for taking us out of the day to day for a brief wander through a fascinating h history.

Thank you, Caroline – and welcome to my blog. I’m delighted you enjoyed the visit to the Herb Garret! I wanted to offer my readers an interesting day out given the difficult circumstances we are all experiencing. I only wish I could add the scent of sage and lavender to the post as well!