I want to look at what three of Jane Austen’s contemporaries thought of her novels: Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), the inventor of the historical novel, nick-named the ‘the Wizard of the North’ for his spell-binding stories; Princess Charlotte (1796-1817), daughter of the Prince Regent, who died in childbirth; and Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855), author of Jane Eyre. Miss Brontë was one year old when Jane Austen died. But she has some interesting things to say, so I’ve allowed her to remain.

Sir Walter Scott’s marble bust by Sir Francis Chantry, 1841, National Portrait Gallery

We are indebted to John Lockhart, Scott’s friend and biographer, for an insight into what that best-selling novelist had to say about Jane Austen. On March 14, 1826, Scott wrote: Also read again, and for the third time at least, Miss Austen’s very finely written novel of ‘Pride and Prejudice’. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The Big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going; but the exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting, from the truth of the description and the sentiment, is denied to me. What a pity such a gifted creature died so early!

What did he mean by ‘the Big Bow-wow strain’? The 10th Earl of Pembroke wrote of Dr Samuel Johnson (he of the famous Dictionary), ‘Dr Johnson’s sayings would not appear so extraordinary, were it not for his bow-wow way.’ I also came across another 18th century reference to the ‘bow-wow’ sound of trumpets and drums. So I think we can take it to mean ‘a touch bombastic’.

Scott wrote stirring tales of battles and deeds of derring-do, which was not Jane Austen’s style. But it’s good to know that Scott was a real fan and appreciated and admired her qualities.

As he wrote in his diary, on 18th September, 1827: Smoked my cigar with Lockhart after dinner, and then whiled away the evening over one of Miss Austen’s novels. There is a truth of painting in her writings which always delights me. They do not, it is true, get above the middle classes of society, but there she is inimitable.

The stone marking the site of Princess Charlotte’s mausoleum: ‘My Charlotte is Gone’, Prince Leopold.

Princess Charlotte, daughter of the Prince Regent and his estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick, was another Austen fan. She enjoyed what she called ‘studdy’ (her spelling was erratic) and read widely, perhaps borrowing books from her father’s library at Carlton House – and we know that he bought Jane Austen’s novels. Or, perhaps it was a birthday present for her sixteenth birthday on January 6th. Whichever it was, on 22nd January, 1812, Princess Charlotte wrote to her friend, Miss Mercer Elphinstone: ‘Sence and Sencibility (sic) I have just finished reading; it certainly is interesting, and you feel quite one of the company. I think Maryanne and me are very like in disposition, that certainly I am not so good, the same imprudence, etc., however remain very like. I must say it interested me very much.’

It’s easy to sympathize with Charlotte’s identification with the passionate and impulsive seventeen-year-old Marianne, who is just the sort of character to appeal a lonely and romantic-minded girl, whose life, up to that point, had been pretty miserable. Perhaps Charlotte hoped that, like Marianne, she, too, would find love. Alas, her story ended tragically, for she died in childbirth aged only twenty-one.

Charlotte Brontë by George Richmond, chalk, 1850, National Portrait Gallery

Charlotte Brontë’s reaction to Jane Austen’s novels is very different. ‘Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point,’ she wrote to the Victorian man of letters, George H. Lewes, who had been pushing them at her. ‘And what did I find? An accurate, daguerreotyped portrait of a commonplace face; a carefully-fenced, high-cultivated garden with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of a bright, vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck.´

When I think of Elizabeth Bennet’s energetic walk to see her ill sister at Netherfield, ‘crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and spring over puddles, with impatient activity; and finding herself at last within view of the house with weary ankles, dirty stockings, and a face glowing with the warmth of exercise,’ I find myself wondering if we’re talking about the same author.

Charlotte has more complaints. ‘Anything like warmth or enthusiasm, anything energetic, poignant, heartfelt, is utterly out of place in commending these works.’

Look at Marianne Dashwood’s reaction on getting Willoughby’s letter repudiating their relationship. ‘Misery such as mine has no pride, I care not who knows that I am wretched. The triumph of seeing me so may be open to all the world… I must feel – must be wretched…’ Surely, Charlotte Brontë cannot interpret such a passionate outpouring as cool and unfeeling.

Later, Elinor notes that, ‘No attitude could give her ease; and in restless pain of mind and body Marianne) moved from one posture to another, till, growing more and more hysterical, her sister could with difficulty keep her on the bed at all…’

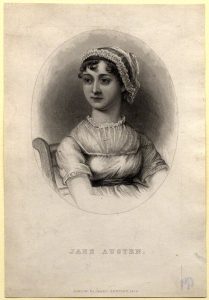

Jane Austen after Cassandra Austen, stipple engraving, published 1870, National Portrait Gallery

And what about Anne Elliot, in Persuasion; mentally comparing her cousin Mr Elliot with Captain Wentworth? She thinks: ‘Mr Elliot was rational, discreet, polished, – but he was not open. There was never any burst of feeling, any warmth of indignation or delight, at the evil of good of others. To Anne, this was a decided imperfection.’ Charlotte would surely have agreed.

I fear that Charlotte was blinded by prejudice. Once she’d decided that Jane Austen’s novels were limited in their emotional range, she refused to look deeper. Austen’s novels might have no mad wife in the attic, as Charlotte does in Jane Eyre, but don’t tell me that Lady Catherine de Bourgh, or the unpleasant Mrs Norris, or General Tilney, weren’t quite as destructive of Elizabeth, Fanny or Catherine’s comfort in their own way.

I rest my case.

Photos of Sir Walter Scott, Charlotte Brontë and Jane Austen courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Oh this is lovely.

I knew that Princess Charlotte was a fan of Marianne but not that she shared my birthday. Delightful. And so pleased that dear Walter Scott knew himself so well.

As for Charlotte Bronte – I fear that Miss Austen would have thought the Parsonage NOT a well-regulated household. Between Patrick, Bramwell and the shadow of death, the Brontes’ own lives seem to have teetered on the edge of melodrama a fair old proportion of the time.

Your comment made me laugh, Jenny. You are so right! There’s more than a touch of Cold Comfort Farm about the Bronte parsonage. Perhaps Charlotte saw Jane Austen as a threatening Flora Poste-type figure.