John Ruskin (1819-1900), an art critic and a man who held strong views on what values a society should hold, was one of the most influential men of his generation. For example, when Lucy Honeychurch, heroine of E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View (1908) visits the church of Santa Croce in Florence, she’s desperate to know which tombstone was praised by Ruskin. This is her first trip abroad and she’s unsure of her own taste; she needs the reassurance that she’s admiring the right one.

However, I think it’s fair to say that Ruskin is not always an easy person to appreciate in the 21st century. Nowadays, we like to view ourselves as liberal-minded and tolerant, particularly in sexual matters. An intellectually very gifted only child, Ruskin was brought up on strict Puritanical principles and cossetted by both parents. His mother had high moral standards and was a very controlling parent. It is not surprising that Ruskin turned out to be obsessive, sexually inhibited and highly-strung.

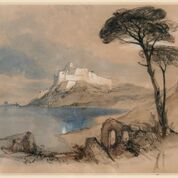

Watercolour sketch of a coastal scene with fortress by John Ruskin, 1841

He believed that women should be pure in mind and body. He once said, ‘Each book that a young girl touches should be bound is white vellum.’ My initial thought when I first read this was that his mother had a lot to answer for. When we learn that his marriage was annulled on grounds of non-consummation – and, as artistic executor, he destroyed most of J.M.W. Turner’s erotic drawings and paintings after the artist’s death, on the grounds that they were disgusting and degrading, it is easy to dismiss him as neurotic and a man whose opinions need not be taken seriously.

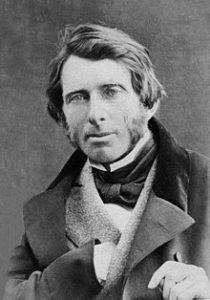

Photograph of John Ruskin, 1863

However, Ruskin was a far more interesting and complex man than the above paragraph indicates; he was a passionate believer in the power of knowledge to create a better world. And he was not afraid to ask awkward questions:

‘Which of us …is to do the hard and dirty work for the rest – and for what pay? Who is to do the pleasant and clean work, and for what pay?’

A hundred and fifty years on, we still haven’t answered this satisfactorily. Ruskin believed that, ‘That country is richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings.’ From Unto this Last, 1860. The Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan is the only country I know of who takes Gross National Happiness seriously – I’ve never heard it mentioned as part of Government thinking in the UK, even as an aspiration.

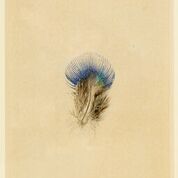

Peacock’s feather. ‘I have to draw a peacock’s breast feather, and paint as much of it as I can, without having heaven to dip my brush in.’ John Ruskin

Not only did Ruskin believe that, ‘Labour without joy is base. I hold it for indisputable, that the first duty of a State is to see that every child born therein shall be well housed, clothed, fed and educated, till it attains years of discretion’. He felt very strongly that, as well as having access to education, everyone – and he included the working man – had a right to access to beauty and nature. In the mid-19th century, these views were Radical. Perhaps they still are.

Façade of the Duomo in Lucca, Italy. ‘When we build, let us think that we build for ever.’ John Ruskin, 1849

A true polymath, he was an art critic, superb draughtsman, social thinker and interested in a wide range of subjects including architecture, art, nature, and geology. His ideas and beliefs influenced Mahatma Gandhi, William Morris, the Garden City movement and many founder members of the Labour Party. He championed artists from Turner to the Pre-Raphaelites, and, rather surprisingly perhaps, supported women’s education.

Copy of Giovanni Bellini’s portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan by Octavia Hill. The original is in the National Gallery

For example, he taught the philanthropist and social reformer Octavia Hill (1838-1912) painting, and supported her project for improved social housing; investing in it and putting it on a firm business footing.

A fascinating new exhibition at 2 Temple Place, London, celebrates Ruskin’s prescient views on the arts, education, the environment and, above all, the welfare of the working man. Ruskin wanted the world to be a better place to live in – for everyone. He felt passionately that people should enjoy the work they did.

Plaster cast of Aristotle. ‘I believe the right question to ask, respecting all ornament, is simply this: Was it done with enjoyment – was the carver happy while he was about it?’

The exhibition brings together over 190 objects: paintings, drawings, daguerreotypes, plaster casts, minerals and books, many from the Guild of St George in Sheffield, a charity Ruskin founded in 1871 to enable the working man to enjoy what art and nature had to offer and to deepen their appreciation. Other museums have also lent objects.

‘Leaf‘ by John Ruskin. ‘Not only is there but one way of doing things rightly, there is only one way of seeing them, and that is, seeing the whole of them’ John Ruskin, 1859.

In Sheffield, the objects are deliberately not labelled; viewers are expected to make their own connections. Ruskin wanted the working man to learn to look deeply. The curator was on hand to explain things to anyone who was interested. It opened from early morning until late at night to enable working men to enjoy it – even if only for fifteen minutes. The Saturday half-holiday movement, that is, shops closing at 2 pm on a Saturday, was gaining ground by 1871 but it was by no means universal. But the Guild of St George went one better and deliberately opened on a Sunday – a revolutionary, not to say shocking, innovation at the time. Ruskin understood that the working man had very little leisure and Sunday openings was a way of making the objects more accessible.

2 Temple Place, looking down the stairwell

Thankfully, at the 2 Temple Place exhibition, the objects are labelled but Ruskin’s original intention of allowing the viewer to have an input comes across in how the exhibits are displayed. 2 Temple Place, once the home of millionaire, William Waldorf Astor, is a quirky Gothic/ Arts and Crafts building with a forceful personality of its own, but Ruskin’s eclectic range of objects more than hold their own.

Amethyst. ‘Remember that the most beautiful things in the world are the most useless.’ John Ruskin, from The Stones of Venice, 1851-3

The exhibition allows us to appreciate the breadth of Ruskin’s vision and the depth of his interest in subjects which are of increasing concern in our own century. His way of seeing has much to teach us.

John Ruskin: the Power of Seeing is on at 2 Temple Place until 22nd April, 2019. Entrance is free. www.twotempleplace.org www.guildofstgeorge.org.uk

Photographs: 2 Temple Place stairwell and Amethyst by Elizabeth Hawksley; photograph of John Ruskin, 1863, courtesy of Wikipedia; all other photographs courtesy of 2 Temple Place.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

This is fascinating, Elizabeth. I used to all I could find by John Ruskin – but then he wrote and published a lot and in the end it was just overwhelming.

He is certainly interesting – and was amazingly confident of his views on art, buildings, history and social priorities from a very early age and never seems to have had a moment’s doubt about any of it. Perhaps that was another quality attributable to the mother?

I loved your last sentence, Sophie; it made me laugh. But, of course, you could well be right. Ruskin was a great hater, too. He loathed railways, for example – he felt that they destroyed views and, by extension, Nature. Personally, I think that railways can enhance a view – a steam train chugging through the Scottish Highlands can be a thing of beauty, for example. Bicycles made him practically incandescent – I’m not sure why. The invention of the Safety Bicycle with pneumatic tyres and proper brakes in the 1890s allowed working men to get to work faster and more cheaply which you’d have thought he’d have approved of. It was also a very liberating invention for women and allowed them to get to places unchaperoned which would otherwise have been impossible.