This year, the Queen’s Gallery marks 500 years since the death of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) with a thrilling new exhibition which displays over 200 drawings held in the Royal Collection. What makes them so extraordinary is that you feel at once that you are being allowed inside the head of a genius, a man who was, above all, curious to know how things worked.

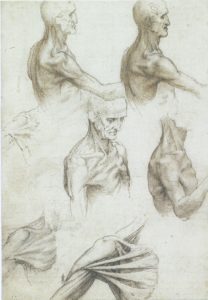

1. Study of shoulder muscles from sketchbook of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of a lawyer, born in 1452 near the small village of Vinci just outside Florence, and brought up by his father’s grandfather. He was apprenticed at fourteen to Andrea del Verrochio, an eminent artist in Florence. Verrochio was more than just an artist, he was also a sculptor, a goldsmith and a maker of beautiful things – whatever his lord, Lorenzo de Medici, wanted, from a painting or a goblet to a suit of armour. Lorenzo, known as The Magnificent, was very much a Renaissance prince with a taste for luxury and the newly re-discovered glories of the Classical past.

2. Goose quill pens and the ingredients for ink, a mixture of oak galls, iron sulphate and gum arabic, a resin which thickens the ink

Leonardo did not really fit into the sophisticated Florentine world around him. For a start, he knew neither Latin nor Greek, and, for all his talent, he may have been regarded as somewhat uncouth. As he wrote, ‘They will say that because of my lack of book learning, I cannot properly express what I desire to treat of. Do they not know that (I)… require experience rather than the words of others?’

In other words, to base his knowledge on what the Classical world had done was, for him, merely second best. Leonardo did not want any intermediaries; he was determined to go back to the source, Nature herself. It is an interestingly Protestant thought. Martin Luther (1483-1546), whose life over-lapped Leonardo’s for thirty-three years, also wanted to go back to the source – in his case the Bible – without having to accept only knowledge considered suitable disseminated by the Roman Catholic church. Leonardo felt the same way about his anatomical and scientific studies.

Sketch for Leda and the Swan

It is interesting that Leonardo left us only one picture whose subject was classical: ‘Bacchus’ (1516), a late painting (though his ‘Leda and the Swan’ is now missing). Otherwise, his paintings are either of religious subjects, for example ‘The Last Supper’ or portraits, such as ‘The Lady with the Ermine’.

But once you’ve seen the 200 or so pages of his note books, you realize that what really mattered to him was more science than art. In 1481, he went to Milan to work for the ruthless Ludovico Sforza – a man interested solely in power and warfare. Here, Leonardo worked as a military and civil engineer; he made detailed bird’s eye view maps; he studied the structure of birds’ wings to understand flight; and he did preliminary clay models for a huge statue of Francisco Sforza on horseback – a commission which was never finished: the bronze for the statue was commandeered to make cannon instead.

When the French invaded Milan in 1499, Leonardo fled and obviously found it difficult to settle somewhere new. In 1502 he was Cesare Borgia’s military engineer. He spent 1500-1506 mainly in Florence; he returned briefly to Milan; and in 1513, he went to Rome and worked on a number of Papal commissions.

6. Foetus in womb

The Queen’s Gallery exhibition is hung chronologically and, within that, thematically. There is a section on Leonardo’s sketches of human anatomy, for example. From 1507-12, he dissected corpses to find out how muscles connect to the body and control movement. His drawing of a foetus in the womb is both objective and tender. The child is almost ready to be born but it will never see the light of day.

7. Scene in the arsenal, Milan: a jumble of hoists, cannons etc

There is a section on warfare and military equipment.

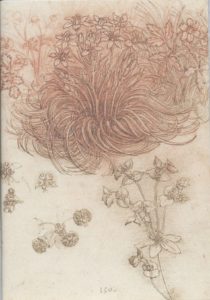

8. Wood anemone, stars of Bethlehem and sun spurge

Another section depicts the natural world, including his sketch of wood anemones, stars of Bethlehem, and sun spurge which is one of my favourites. I love the way that the star of Bethlehem’s leaves swirl about the plant like water. They are beautifully drawn and I had no difficulty in identifying the flowers.

9. Curator Martin Clayton (left) and photographer Richard York (right) from Rainbow Collective

The curator, Martin Clayton, gave us an excellent introduction to Leonardo in his time and place and explained the why and how of his unusual qualities. He also pointed out that, by the mid-fifteenth century, paper was no longer prohibitively expensive. Even so, Leonardo didn’t waste a single inch and his sketches go right up to the edge of the paper. And where there aren’t sketches, there are notes scrawled all over the gaps in the paper written in his left-handed mirror writing.

10. Women’s Hands

I am left-handed myself, and mirror-writing has the advantage of avoiding smudging words you’ve just written which tends to happen if you are writing left-handed with ink. Leonardo must have discovered that, too.

11. Definitely the horse in motion – with extra legs

There are numerous sketches of horses, cats and other animals. Horses were particularly important to him; the numerous sketches in preparation of his never-completed statue of Francisco Sforza on his horse, are always referred to as ‘the horse’. Francisco himself seems almost incidental.

12. Home-made pencils made with split sticks holding different coloured chalks

I also liked the cases showing the various inks, chalks, charcoal and so on which Leonardo used and how they were made. For example, how to make ink from oak gall, iron sulphate and gum arabic.

It wasn’t until 1516 that François I of France offered him a retreat in France, in Amboise, where he could do as he pleased. By this time, his right arm was paralysed and time was running out. He died in 1519, age 67.

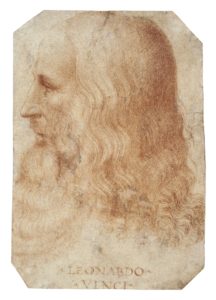

He left his sketches to his favourite apprentice and the collection was put into leather-bound albums, one of which was acquired by Charles II in 1670. It has been in the Royal Collection ever since.

I thought this was a wonderful exhibition and a rare opportunity to see so many of Leonardo’s sketches at once. The small size of the pages force the viewer to look closely and take time to understand what’s going on on the page, but the results are infinitely rewarding, The exhibition is on until 13th October, 2019.

Photos: Royal Collection Trust/(c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, apart from numbers 2,7, 9, 11 and 12 which are by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

I saw a lot of Leonardo sketches while in Florence, many of the faces and heads of young women that were utterly beautiful. I don’t remember where that exhibition was as it’s many moons ago I went, but I do remember some of the sketches and this brought it all back to me. His sketches, Donatello’s David and the San Marco murals were the highlights for me, although every day brought new wonders. It was quite overwhelming. Most interesting to see were the murals and sculptures in process of renovation. You could see how the cleaned parts were so much clearer than those with centuries of grime. The muscles and sinews stood out in the sculptures and the mural colours were extraordinarily bright.

In this regard, the actual Michaelangelo’s David was extraordinarily striking and you realise how little you get the power of it from the reproductions. The same with Botticelli, because you can’t really see the gold. In the flesh it absolutely gleams and brings the paintings to live.

But Leonardo’s paintings were streets ahead of most of his contemporaries and when you see one among a host of others it just leaps out at you. He was an astonishingly gifted artist.

I agree, Elizabeth. Leonardo left very few paintings (only about 20) and many potentially important works were unfinished. None of his monumental equestrian statues were even cast. If it weren’t for the almost miraculous survival of so many sketches and drawings, he might well have been considered a failure and only as an almost mythical genius. It’s the range of his work that is so extraordinary, that, and the meticulous detail.

We have just been in Amboise and visited the Clos Lucé, the manoir Francois I gave to Leonardo after he enticed him to France and where Leonard died in 1519. It seems as if the aging da Vinci lived in some comfort in this charming small chateau and continued his explorations of the physical world almost to the end. The administration of the Clos Lucé has recreated his work room as it might have been during his time there with drawings, maquettes, tools and so on. In the basement they have scaled up and built working models of many of his projected inventions from the notebooks. We particularly liked the self-propelling car and the swing bridge.

The manoir is surrounded by a delightful woodland garden with ponds and a stream as well as a potager or vegetable garden. It is good to think that after his life of wandering Leonardo found so secure and comfortable place to end his days.

How wonderful, Pauline. Lucky you. I’d love to see the recreation of Leonardo’s work room. One thing I particularly liked about the exhibition in the Queen’s Gallery were the cases which demonstrated how one made ink at that date; the sort of goose quills he used; how he used metal point and silver point, and the sort of small shells he used to hold his pigments. The artist was much closer to his materials in the 15th century – Leonardo could have his ink exactly what thickness or thinness he liked. Nowadays, the paint/ink manufacturer decides all that for one.