This week I’m in Rochester, an important naval town on the River Medway which flows into the Thames. There is a huge amount to see in Rochester from Roman times onwards, but today I’m looking at one house.

Being a Charles Dickens fan, I have long wanted to visit Restoration House, supposedly Dickens’ inspiration in Great Expectations for Miss Havisham’s home, Satis House, that ‘large and gloomy’ place, full of dust, cobwebs and shadows and lit only by candlelight. It is here that the young Pip is entrapped by Miss Havisham’s desire to seek revenge, through him, for her lover jilting her so cruelly on her wedding day.

Restoration House

However, I’m starting with the real Restoration House. Its early history is sketchy but it probably originated as two parallel buildings, the South Building dating from 1454 (floor joists under what is now the Oak Saloon have been dated to 1454) while the North Building dates from the early 16th century. At some point later that century, the two buildings were united, possibly by a Great Hall. Rooms were added and altered; some disappeared and became something else, like stairs. Windows and doors were blocked up; new ones were created. No wonder that the quaintly named Eccentric Room is so called because none of the experts could make head or tail of its architectural anomalies.

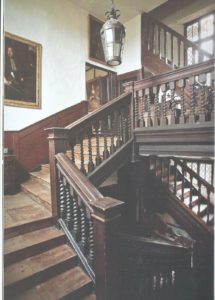

The King’s Stair, dating from 1684

The house, however, was to have its moment of glory. In May 1660, Charles II was invited back from exile after the collapse of the Commonwealth on Cromwell’s death. He needed somewhere to stay on the night of May 28th before his ship carried him up the Thames to London. The house was large and important enough to be considered suitable and it was conveniently owned by a Royalist, a Mr Francis Clerke. Perhaps one of the reasons for the choice was that the Oak Saloon and Tapestry Room on the ground floor, which were to be put at the King’s service, had its own, separate, entrance. Security would surely have been important.

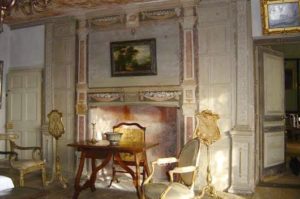

The Oriel Room on the first floor

Interestingly, the rooms’ names are generic (the Great Hall, the Great Chamber, the Oriel Room) rather than being specific (Lady’s dressing-room or Dining Room, say). We don’t know what each room was actually used for and, over the centuries, the usage probably changed. The only spaces that are named specifically are the King’s Bedchamber and the King’s Stair and their locations, after King Charles’s momentous visit in May 1660, were unlikely to have been forgotten..

It is certainly a house of great character and one wonders what Charles made of its higgledy-piggledy charm. Embarrassingly for Mr Clerke, his house was let to a Colonel Richard Gibbon who had fought for Parliament. Still, the Colonel, who was known to be disenchanted with the Commonwealth, might be persuaded to move. It sounds as though the Colonel took himself elsewhere because some necessary alterations were made to accommodate the King, who graciously knighted Mr Clerke during his visit. Colonel Gibbon doesn’t even get a mention.

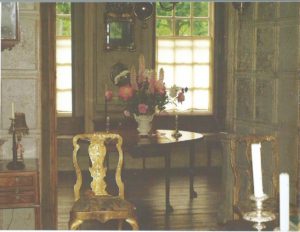

Looking through the open double doors of the Oak Saloon into the Tapestry Room

Research tells us that, about that time, the Oak Saloon had a makeover in emulation of what was thought to be fashionable in Paris – the ‘in’ colour was French Grey, traces of which have been found. The makeover was obviously aspirational on Mr Clerke’s part; Charles had spent part of his exile in Versailles, home of his first cousin, Louis XIV. The panelling of the west wall was turned into a double-doored entrance into the Tapestry Room beyond it, which allowed it to transform neatly into an audience chamber, and the double doors could be closed for privacy. At the same time, it gave the King, who was over six foot tall, an entrance he could use without cracking his head.

17th century harpsichord, said to have belonged to Queen Christina of Sweden

Charles would surely have wanted to please all those he met. His teens and twenties had been difficult. His childhood had effectively ended when the Civil War broke out when he was fourteen and he’d gone to war with his father. When the Civil War ended in victory for Cromwell’s New Model Army, Charles had fled into exile, and in 1649, aged eighteen, he’d learned of his father’s execution. He was crowned by the Scottish Covenanters Army at Scone in 1651 and then had to endure the humiliatingly strict Presbyterianism they forced upon him. When the Second Civil War ended badly, Charles fled again, this time to France. Now, he had been invited back to England – as King – and May 29th, the day he would be entering the once staunchly Parliamentarian City of London, was his 30th birthday.

It was Charles’s momentous visit which caused the house to be renamed ‘Restoration House’ – it is not clear what it was called prior to that.

The house has a very distinct atmosphere. The floors are bare polished wood, the colours of the walls are muted and you have to allow your eyes to become accustomed to the gloom. It is a peaceful and friendly house to be in – there are vases of flowers from the garden everywhere. As well as quality 17th and 18th century furniture, there are also some very good paintings: I liked the early Constables, for example.

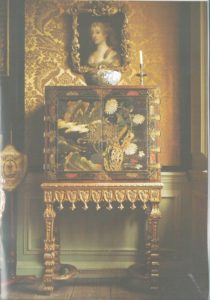

The lacquer cabinet and the portrait of the Duchess of Cleveland by Sir Peter Lely in the King’s Bedchamber

The furniture and fittings are mainly 17th and 18th century. I like the William & Mary lacquer cabinet on a giltwood stand in the King’s bedchamber. The decorated cabinet doors have been made from an early 17th century Chinese screen. I love the white chrysanthemum flowers, symbols of both Autumn and longevity in Chinese culture.

The painting above the cabinet is of the Duchess of Cleveland by Sir Peter Lely, Principal Painter to Charles II. The Duchess, nee Barbara Villiers, became Charles’ mistress in 1660 and he acknowledged the paternity of five of her children. One has only to look at those bedroom eyes, the swell of her breasts, the long ringlet negligently resting on her shoulder to see why her portrait graces the King’s bedchamber wall.

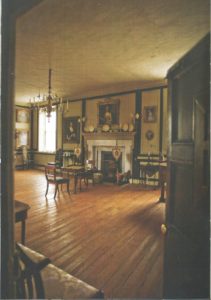

The Great Chamber, said to have inspired Miss Havisham’s room in Dickens’ Great Expectations.

It is not difficult to see why the Great Chamber inspired Dickens’ creation of Miss Havisham’s Room: the light from the two sash windows show up the warm glow of the pine floor, but otherwise, the place is dimly seen. The wall panelling has been restored to the stone white and off black Sir Francis Clerke gave it in the 1680s.

When Pip visits Miss Havisham, we are told that it was ‘well lit by candlelight’ But all that Pip can see are things that were once white now turned yellowish with age and dusty looking with neglect: her wedding-dress, the wedding cake, the flowers.

It’s a curious feeling entering a house which has a very strong history of its own but also has a separate ghostly, fictional alter ego.

The outside yard, leading to the tradesman’s exit.

After Pip and Estella have played cards for Miss Havisham’s entertainment – she enjoys watching Pip lose humiliatingly – Estella is told to give Pip something to eat and drink before he goes. Estella takes Pip downstairs and leaves him in the yard by the side of the house. When she returns with some bread, meat and a mug of ale, ‘She put the mug down on the stones of the yard, and gave me the bread and meat without looking at me, as insolently as though I were a dog in disgrace.‘

When I found the back yard, I recognized it instantly. Maybe this isn’t the yard Dickens had in mind, but it fits.

Restoration House from the back.

In Great Expectations, the garden of Satis House is ‘rank‘ and ‘overgrown with tangled weeds‘; in Restoration House, the garden is beautifully laid out and obviously well looked after. It has undergone years of research and restoration to bring it back to its former glory.

There is a friendly cafe with delicious cake and people are sitting outside, enjoying the sunshine. The contrast could not be more different from Pip’s experience.

Thenji enjoying watering the garden

Restoration House is open June – September, Thursdays and Fridays, 10 am to 5 pm. The visitor experience is enhanced by the friendly and knowledgeable volunteers who tell the visitor about the various rooms as you walk around the house; offer you tea, coffee and delicious home-made cake in the cafe; and, outside, look after the wonderful gardens.

www.restorationhouse.co.uk

All photos inside the house courtesy of Restoration House. Photographs outside the house by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

How interesting. A beautiful house. I love that staircase, which seems to have another piece going down a different direction. Or is that a different stair? All that fabulous wood everywhere is evocative of those earlier days. The connection with Miss Havisham’s house is extraordinary. Love these little tidbits of historical detail.

It is an extraordinary house, isn’t it? The stairs in the photo are actually two separate staircases built at different times and going in different directions. There’s more than a touch of Alice in Wonderland about the place.