Roger Fenton (1819-1869) was one of the earliest British war photographers, and the Queen’s Gallery is currently showing a selection of his 1855 Crimean War photographs in the Royal Collection. After a tussle with his father, who didn’t approve of his son’s artistic leanings, Fenton was eventually able to follow his heart. He discovered photography when it first appeared in the late 1840s, immediately recognized its potential and set himself to master it. In 1852, he travelled to Russia, visiting Moscow, Kiev and St Petersburg, and, on his return, he toured an exhibition of his photographs around Britain, which established his name. It also led to his involvement in the founding of the Photographic Society of London, where he promoted this new medium, and became its first honorary secretary.

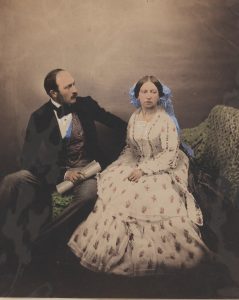

He was obviously good at networking which was as important then as it is now. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert came to the Photographic Society’s first exhibition in 1854 and, as honorary secretary, Fenton was, naturally, the man who showed them round. The royal couple subsequently commissioned him to take photographic portraits of themselves and their children. Not everyone was in favour of this upstart medium; the painter J. M.W Turner feared that photography might signify ‘the end of art’ others were suspicious of a medium whose practitioners felt no need of an artist’s trained and discriminating eye. But royal approval gave photography the status it needed.

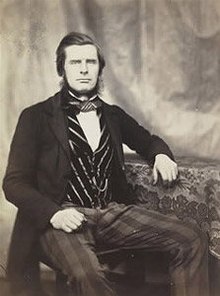

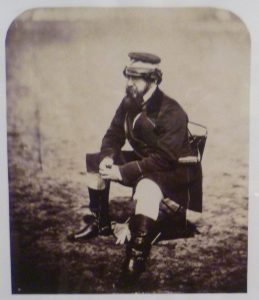

Roger Fenton, self-portrait

In fact, Fenton had trained briefly as an artist in Paris, and this training was about to prove its worth when he was commissioned by the leading print seller and fine art publisher, Thomas Agnew, to go the Crimea as a war photographer.

The Crimean War broke out in 1854 with the allied Ottoman Turks, the French and the British on one side, and Russia on the other. Ostensibly, the Russian were the (self-proclaimed) protectors of Slav Christians living under Ottoman rule and they invaded Turkey to protect them. The Turks declared war, swiftly followed by France and Britain, who suspected that Russia’s real agenda was to expand their Empire to include Constantinople and gain access to the Mediterranean.

The Crimean War was the first major conflict Britain had been involved in since the battle of Waterloo which ended the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The huge British Crimean death toll of 22,000 men, most of which was caused by disease and deprivation – munitions not arriving, no winter clothing for the troops, no proper food supplies, appalling medical facilities and so on – immediately showed up the incompetence of the Commissariat, the Treasury department responsible for the organization and distribution of military personal and supplies. The appalling conditions were exacerbated by the ineffective leadership of the elderly commander-in-chief, Lord Raglan.

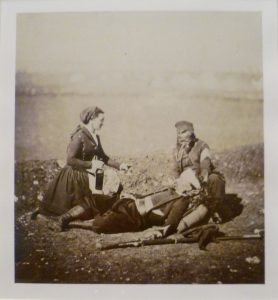

A French vivandière tending to a wounded Zouave, a Berber soldier from the French colony of Algeria

The French army was a lot more efficient and their men were consequently in much better condition. There was a contingent of non-combatant females, the vivandières, usually married to junior officers, who fed and tended to the soldiers when they were wounded, dealt with the laundry and so on.

William Howard Russell (1820-1907)

It was not long before news of disarray in the army got back to Britain, and The Times sent out their War Correspondent, W. H. Russell, to investigate. His reports pulled no punches and his observations were damning. He witnessed the disastrous charge of the Light Brigade on 25th October 1854 which thundered down a heavily-defended valley with Russian cannons blazing on every side, and wrote: ‘The whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame through which hissed the deadly balls … the plain was strewed with bodies and with the carcasses of horses…’

Five months after this heroic but catastrophic event, Fenton arrived in Balaklava in March 1855, armed with a letter of introduction from Prince Albert. The article on Fenton in The Dictionary of National Biography describes his war photos thus: Fenton’s education as an artist lead him to represent the war as a series of heroic portraits, tableaux, and expansive battlefields that implied a nobility of spirit and sense of moral purpose profoundly at odds with the realities of the Crimean campaign.

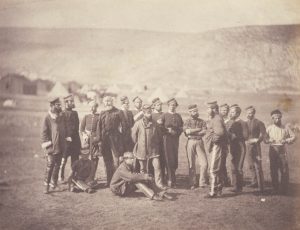

The current Queen’s Gallery exhibition’s curator of Shadows of War: Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, 1855 disagrees. She says: The first exhibition of Fenton’s Crimean works in London since 1856 explores how the photographer brought the stark realities of war into the public consciousness for the first time. She goes on to say: The limitations of 19th-century photographic techniques, coupled with Victorian sensibilities, prevented Fenton from producing scenes of battle and death. Instead, he evoked the destruction of war through portrayals of bleak terrains and haunted troops.

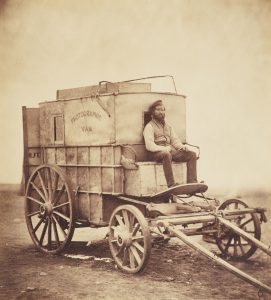

The technicalities of taking a photograph in 1855 were daunting.

Fenton brought two servants with him: a handy-man and cook, and a photographic assistant who also looked after the horses. It was impossible for him to take action photographs with an exposure time of between 3 and 20 seconds. To take a photograph, Fenton had to coat a glass plate with an emulsion of wet collodion in the van, insert it into the camera, take the photograph, and rush it back to the van for processing before the collodion on the plate dried – five minutes maximum.

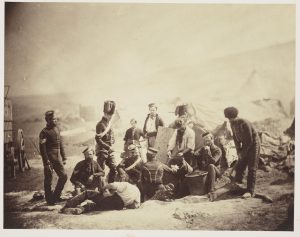

Action photos would obviously come out blurred. Fenton’s photos had to be posed and static. Take his photo of the 8th Hussars cooking hut above. The hut is just visible on the left; and eleven men, including an officer, distinguishable by his shako and the frogging on his jacket, stand or lounge around. In the background, a soldier’s wife is waiting to help. Two large pails of food are on the ground. It is obvious that the cooking facilities are extremely basic; it might be described as a tableaux but it is hardly ‘heroic‘.

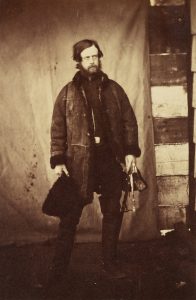

Balgonie, the eldest son of the Earl of Leven, served in the Grenadier Guards during the Crimean War. This photograph has been described as the first photographic portrait of shell-shock. There is no ‘nobility of spirit’ here. He reminds me of those soldiers with staring eyes which have seen too much in the trenches on the Western Front. Poor Blagonie, and he was only twenty-four, looks haunted and desperate. He survived the war but died two years later, a death attributed to the hardships he’d undergone.

The British Commander-in-Chief, Lord Raglan (1788-1855) had immense prestige and was a brave and unflappable soldier – he lost an arm at the battle of Waterloo – but by 1854, he was too old and set in his ways and was a disaster as Commander-in-Chief. General Omar Pacha (1806-71) who commanded the Ottoman army, was an interesting man. Born Michael Lotis, a Serbian Christian, he converted to Islam and rose swiftly through the ranks to become famous as a general, winning several spectacular victories over the Russians during the Crimean War. He was much admired by the British.

Omar Pasha’s popularity in Britain is demonstrated by his image the figureheads display on the

Cutty Sark, Greenwich.

As for the French commander, Général Pélissier, Fenton called him, ‘That bastard Pélissier.’ The French army was much bigger than the British army and far better managed. Pélissier infuriated the British by bringing the French attack on the strategic Malakhoff Tower forward by two hours without consulting his allies. The result was a military disaster.

The title of the photograph is taken from Psalm 23, and which also, probably deliberately, echoes the phrase ‘the valley of death’ in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ which appeared in The Times in December 1854 and instantly attained almost mythic status.

Fenton visited the valley above on 23rd April, 1855. It is not the Charge of the Light Brigade site, but he is, perhaps, paying them a subtle tribute in the photograph. It is a barren and desolate place and the foreground is covered in cannon balls. Its sombre bleakness is curiously impressive (though Fenton collected some more cannon balls to augment those already there). He did so at some personal risk; he was shot at by Russian sharpshooters, and had to retreat in haste.

When Fenton returned home in July 1855, his war photographs went on display in four London venues. For the first time, people could see the battlefields and the conditions endured by ordinary soldiers for themselves. Queen Victoria herself took a personal interest both in the conflict and in the wounded and discharged soldiers, and she was the first monarch to visit ordinary soldiers in hospital and invite them to Buckingham Palace. She also instituted the Victoria Cross, the Armed Forces highest award for gallantry.

Shadows of War: Roger Fenton’s Photographs of the Crimea, 1855 is on at the Queen’s Gallery, together with Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs. Both are on until 28th April, 2019 and are well worth seeing. I loved the contrast between the spectacular artefacts in the Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs exhibition and Roger Fenton’s low-key but moving war photographs.

All photographs by Roger Fenton, except the self-portrait, are courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2018. Fenton’s self-portrait is courtesy of Wikipedia. The photograph of the Omar Pasha figurehead is by Elizabeth Hawksley.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

That’s extraordinary and poignant. And what an unusual image of Victoria and Albert. Seeing early photographs really brings the past to life. And it must have been a revelation to those at home who had never known the hardships of war.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. I think Roger Fenton must have got on well with both Queen Victoria and Prince Albert – who became enthusiastic patrons of his work. By an extraordinary coincidence, they were all born in 1819, and maybe being exact contemporaries helped; they would have understood the zeitgeist of the times they all grew up in – immediately post-Napoleonic Wars; about ten years old when the railways began to make an impact, and so on.

Gosh, what evocative photographs produced under very trying conditions. It really brings the Crimean War home to you.

Thank you, Jan. I agree that the grainy photos really bring home the wretched conditions in the Crimea at the time. It’s a far cry from the heroic paintings of the period with men in scarlet jackets, on horseback and waving swords, and charging at the enemy – with everything clean and shiny. The reality must have been very different. I wish I’d had the space and time to quote W. H. Russell’s article in ‘The Times’ about the Charge of the Light Brigade in full. He doesn’t pull his punches about the blood, mud, wounded and screaming horses, and so on. As a French General watching the charge said, ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre. C’est la folie.’ (‘It’s magnificent, but it isn’t war. It’s madness.’)