On a cold winter’s day, 29th December, 1170, three knights: Reginald Fitzurse, William de Tracy and Hugh de Morville arrived at Canterbury Cathedral. They were King Henry II’s loyal men and, time and again, they had heard him fume against the Archbishop Thomas Becket’s wilful refusal to obey him and side with the church instead. They vowed to ride to Canterbury Cathedral, capture Becket, and drag him back to face the King, so that the long and bitter quarrel between them could finally be settled.

They did not, at this point, mean to murder Thomas.

A reliquary casket showing the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. At the bottom, three knights, swords raised, are about to attack Thomas who stands in front of the altar. Two monks on the right raise their hands in horror

So, who was Thomas Becket? For a start, he was considered an upstart by many – his father was a mere merchant of Norman origin, who moved to London for business reasons. The family settled in Cheapside, a lively, cosmopolitan area near St Paul’s Cathedral. Thomas was born in London around 1120, and educated in both London and France. He was a tall, good-looking man, with a fair skin and dark hair. He held himself well, his manners were excellent, and, he was a good talker. His education was no more than adequate but he made a good impression, and he knew how to please.

His big break was becoming a clerk to Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Henry II had inherited a fractured kingdom. His mother, the Empress Matilda, was the daughter of King Henry I and next in line to the throne – but she was female. There was a large faction who wanted Stephen, Henry I’s nephew, to take the throne instead. Neither Stephen nor Matilda would give way and the country slid into civil war. Eventually, a settlement was reached; Stephen would be King for his lifetime, and then Matilda’s son Henry would become King, as Henry II.

A pilgrim’s memento of a visit to Becket’s shrine: a ship brings Thomas Becket back to Canterbury after his exile

King Henry II needed a new Lord Chancellor, someone who would be loyal only to him, and Archbishop Theobald recommended the young, talented Becket as a suitable candidate. Henry and Becket hit it off and became close friends; this brought Becket wealth and power, and Henry benefitted from Becket’s ability to rein in would be troublemakers.

One of Henry’s most worrisome problems was trying to contain the power of the Catholic Church. As it stood, a man in Holy Orders who had committed a crime could only be tried by an ecclesiastical court, not by a secular one. Henry disapproved.

When Archbishop Theobald died in 1162, Henry wanted his friend Thomas Becket to become Archbishop of Canterbury – as well as being Lord Chancellor. That way, he, Henry, would be able to curtail the power of the Catholic Church. Becket did not want the job and he fought against the appointment. For a start, he was a worldly man, who led a thoroughly worldly life; he wasn’t even in Holy Orders.

Alabaster panel from an altarpiece showing Becket’s consecration as Archbishop of Canterbury. Becket, in red, has a bishop on either side. Above, God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit look down.

Henry eventually had his way, but things didn’t turn out as he’d planned. To the King’s fury, Becket instantly gave up his chancellorship and sided with the Church. He upheld the rights of the Catholic Church against Henry’s wishes.

His relationship with the King became so poisonous that Becket, fearing for his life, fled to France. The King retaliated by confiscating all Becket’s wealth, and forcing his family into exile. In return, Becket excommunicated the King and all who sided with him. Eventually, a fragile peace was negotiated and Becket returned to England and Canterbury Cathedral. But, on hearing that Becket had excommunicated him, Henry flew into a rage and cried, ‘What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!’ Or, if you prefer the shorter version: ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’ The outburst was heard by three knights: Reginald Fitzurse, William de Tracy, Hugh de Morville who came up with, according to the Dictionary of National Biography ‘an ill-conceived plan.’…

And, although murder was not their original intention – events overtook them and Becket was murdered in front of the high altar.

The whole of Western Christendom was horrified, and, almost immediately, word got round of miracle cures …

This magnificent reliquary comes from Hedalen Stave Church in Norway, and dates from 1220-1250. The cult of St Thomas Becket was second only to that of St Olaf, Norway’s patron saint . The reliquary is decorated with dragon’s heads and is made of copper-alloy with gilding over a wooden base. It actually shines!

What is interesting, is the speed with which the worship of St Thomas spread, particularly to Nordic countries. Thomas was canonized within three years of his death and, in the current British Museum exhibition, there are a number of reliquaries which look very similar to my first photo. Very swiftly, the essentials established themselves, (rather like the essentials for a Nativity scene: the Virgin Mary, Joseph, the infant Jesus, the crib, the ox, the ass, the three shepherds, the three Kings with their offerings of gold, frankincense and myrrh, and so on).

If you turn back to my first photo, you will see the actual murder of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170 in the bottom panel. Thomas is kneeling in front of the altar: the three armed knights are poised for attack; the sword of the first knight slices a bit off Thomas’s skull before falling to the floor and breaking off its point. Two monks on the far side of the altar hold up their hands in horror.

On the roof of the reliquary, Thomas’s body is hastily buried beneath the altar, and at the top right, we see Thomas’s soul entering heaven and being greeted by two angels. The wavy lines under his feet represent clouds.

The impressive baptismal font (1191) from Lyngsjö Church, Sweden. There are grotesque figures carved round the base, but the actual bowl has the martyrdom scene with the altar, Thomas holding a cross, the knights with their swords and so on carved round the rim.

There are always three knights, although the records include a fourth knight, Richard Brito. (I always feel that perhaps he was the one who held the horses so that the murderers could make a quick getaway.)

But, the truth was that they had not intended to murder Thomas, simply to force him to go with them to London. Indeed, Thomas and the knights knew each other – they had worked together when Becket was Lord Chancellor. The whole thing had not been thought through and the knights’ angry impetuosity turned into bloody murder. It sounds to me as though they may have egged each other on.

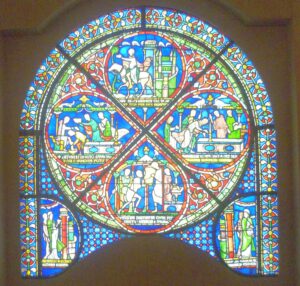

The top arch of the fifth Miracle Window, Canterbury Cathedral, early 13th century

The highlights of the current British Museum exhibition include the wonderful 6 metres high, newly restored, 5th Miracle Window from Canterbury Cathedral which has been lent for the exhibition. It depicts a number of Thomas Becket’s miracles which show how he worked wonders for ordinary people.

Hugh, who fell ill at Jervaulx Abbey in Yorkshire. A doctor offered him medicine – which didn’t work. But then a monk offers him some St Thomas’s water – this causes a nosebleed, after which Hugh feels better. In the roundel, we see him lying on a bed, a stream of red blood from the nosebleed falls to the floor..

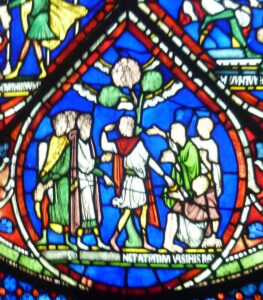

There are four roundels within the window. Below is another of St Thomas’s miracles.

Eilward of Westoning was blinded and castrated as punishment for theft. He prayed to St Thomas who first restored his eyes and then his testicles, symbolized by the large erect plant with two green leaves and a fluffy white flower. Eilward is obviously overjoyed.

The exhibition first shows the visitor the real window, standing 6 meters tall – and I have to say that it is wonderful and lights up the room. And there are also life-size photos of the roundels placed horizontally which tells you what happens in each section, so that we, too, can follow the story, cartoon fashion.

The St Thomas’s water was ordinary water which contained a drop of St Thomas’s blood. Small pilgrim’s flasks of St Thomas’s water were sold to pilgrims.

The exhibition in the British Museum: Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint shows, not only the murder and its immediate aftermath, but also follows the effects of Becket’s murder on the religious and political landscape over the next 360 years or so until Henry VIII ordered Thomas Cromwell to destroy Becket’s shrine in 1538. And even that wasn’t the end of Becket’s influence – far from it.

Those of you who might like to look at my earlier blog: Names: the Rise and Fall of Thomas http://elizabethhawksley.com/names-the-rise-and-fall-of-thomas/ will get a taste of what happened next.

I hope to look at the second half of the Becket story in another post.

Elizabeth Hawksley

I am delighted that my fifth Elizabeth Hawksley: Tempting Fortune, is now out in e-books.

Please share this page...

I always loved the play Murder in the Cathedral and there was the film too with O’Toole and Richard Burton. Have a soft spot for the period because of A Lion in Winter, in which I have acted as well as watched a couple of versions in film. On the whole though, I find Eleanor more fascinating than Becket, but it is an enduring story.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment, Elizabeth. I, too, remember the O’Toole – Richard Burton film. O’Toole was particularly good at tortured angst! – as in ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, for example.

I studied ‘Murder in the Cathedral’ for A level. It’s surprising how many lines from it have passed into common currency: ‘Living and partly living,’ for example.

The Becket story erupted again with the Tudors and Henry’s determination to destroy Roman Catholicism. Very odd because, he’d been on Pilgrimage to Canterbury five times before the Reformation!

I suppose beheadings were a much more common occurrence back when people were carrying swords around all the time.

Oh, Huon! I do enjoy your comments. For the record, an execution, that is, cutting off some poor wretch’s head, was the official punishment for treason until the mid eighteenth century.

Only for nobility. The punishment for ordinary men and women was far worse.

Thank you for your very fair comment, Neil. You are right – at least about ordinary men being hanged, drawn and quartered – not to mention being tortured first. But were women drawn and quartered as well as men? I don’t remember any instances of that.