The Strand Magazine (1891-1950) was one of the most popular magazines of the late Victorian Age; it came out monthly and I have my Great-Grandfather’s copy of the first hardback edition of The Strand Magazine, Jan-June, 1891. It contained short stories, some translated from foreign languages; e.g. Russian (A. Pushkin); and French (Victor Hugo), together with articles of general interest. It was fully illustrated and targeted a middle-brow, middle-class readership; with something for everyone. The list of authors who wrote for The Strand Magazine was impressive and included Agatha Christie, Rudyard Kipling, and P. G Wodehouse. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories were serialized in The Strand Magazine, where Sidney Paget’s illustrations defined what Holmes looked like so perfectly that it’s now impossible to visualize him any other way. The magazine was phenomenally successful and, until the Second World War, it regularly sold 500,000 copies a month.

Strand Magazine bound copy January-June 1891

The editor, Herbert Greenhough Smith, needed ‘names’ to attract the readers, and the cost of translating foreign short stories by well-known authors was cheaper than commissioning new stories by British writers – though he did that, too. A number of articles were anonymous, and here he must have used his reporters, as he did for the Child Workers in London article. It comes under investigative journalism but with a soft edge. The Strand Magazine was not interested in campaigning; instead, a reporter researched the interesting topic the editor wanted, an illustrator added his or her bit, and the resulting lively and intelligent article – plus illustrations – left the readers to decide for themselves what they thought.

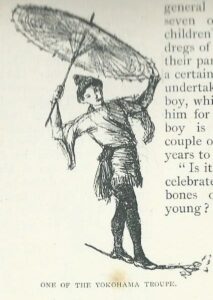

Knife throwing practice: the Yokohama Troupe

The Child Workers in London article on education caught my attention, especially the sections which dealt with the young boys who trained as trapeze artists for Edwin Bale’s Yokohama Troupe, and the young girls who trained under Mr D’Auban as dancers at various West End theatres.

Forster’s Education Act of 1870 had given every child between the ages of 5 – 12 an education in the three Rs – at least in theory. But if you came from a theatrical or circus family, say, your education might be sketchy – especially if your family desperately needed your financial contribution.

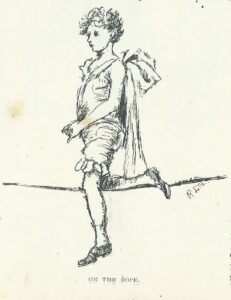

On the rope practice

Beginning with the young acrobats; the reporter observed that, ‘The general impression, derived from sensational stories in newspapers, is that the profession of gymnast is a disreputable one … And that young acrobats can only be made proficient in the art by the exercise of severity and cruelty on the part of trainers.’ The reporter interviewed several trainers. ‘Of course,’ said an experienced trainer, ‘I would lay a heavy wager that even a lazy lad sheds less tears in his training with me than a dull schoolboy at a public school. I have never met with a single boy who didn’t delight in his dexterity and muscle; and you will find that acrobats as a whole enjoy a higher average of health than any other class.’

He could well be right, I thought, given the brutalities we know went on in Public Schools at the time.

Ball exercise – good for balance

An acrobatic troupe was often a family business and comprised five or six family members, but it could also include non-family (remember Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby who joined Victor Crummles’ theatrical troupe). The ‘father’ of an acrobatic troupe could take on apprentices; he undertook to feed, clothe and teach a boy for a set number of years, and the parents agreed not to claim him. ‘A boy is rarely any good for the first couple of years, and it takes from five to six years to turn out a finished gymnast.’

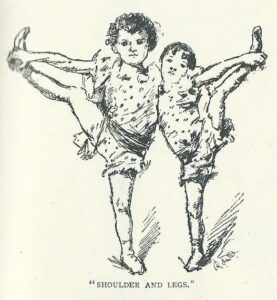

Shoulders and legs – muscle-stretching exercise.

The reporter then interviewed Mr Edwin Bale, ‘head of the celebrated Yokohama Troupe’. (I confess that I’d never heard of them.) Edwin Bale was the eldest of a large family of boys who were inspired as children by a Chinese Juggler. The brothers trained themselves in juggling, acrobatics and bicycling. Bicycles had just come in and, as the boys swiftly discovered, could be turned to good account with ‘wheelies’, acrobatics on handlebars and so on. Gradually, they began touring and did well enough to earn a living.

After many years in the Americas, the group eventually became the Yokohama Troupe, a name Edwin Bale thought was ‘a stroke of genius’, and returned to England.

One of the Yokohama Troupe on the tightrope; obviously the Yokohama Troupe’s nod to Japan

Japan had made a huge impression on the west at two major international exhibitions in London and Paris in the 1860s which triggered an artistic response from artists like Manet, Whistler, and Van Gogh; Gilbert & Sullivan celebrated things Japanese with The Mikado in 1885; and blue and white ‘Japanese’ ceramics became all the rage.

The Yokohama Troupe would fit in nicely.

The reporter, rather rudely I thought, then asked Edwin Bale if ‘the bones of the boys are often broken whilst young.’ Mr Bale promptly invited him to come and watch his troupe practice; and added that they practiced regularly for two or more hours a day.

Full spread. The boys look like the same two in the shoulders and legs exercise.

‘The “Yokohama Troupe” includes three boys, all well-fed looking and healthy. One of them being Edwin, the fifteen-year-old son of Mr Bale, a strikingly handsome and finely-developed boy who has been in the profession since he was two.

‘The first exercise the boys learn is “shoulders and legs” which is practiced assiduously till performed with ease and rapidity. After this comes “splits”.’ They learn the splits, ‘flip-flap’ and ‘full-spread’ In the latter, it is important that the boy on top should be light and ‘slightly–made’.’ It must also surely require a good deal of trust as well.

When I looked in the index, I saw that the illustrations were by a Miss Le Quesne. Rose Le Quesne was well known for her Art Nouveau style illustrations, and her work for Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen (1590) is still in print today. She had obviously brought her sketch book to the interview with Mr Bale, and her swift sketches have a movement and spontaneity which I thought suited the article perfectly.

Young Master Harris, one of the boys, said that he had meat twice a day, a bath every evening, that Mrs Bale was like ‘a mother’ to him, and that performing was ‘jolly’. He got 3 shillings a week pocket money which was put in the bank for him. If he stayed with the troupe once he’d grown up, he could count on between £20-£25 a week, far more than most working men earned at that date. But the Yokohama Troupe could also command between £70-£80 a show when hired out for fêtes or public entertainments, and that didn’t include their regular performances in a theatre. Mr Bale was plainly making money.

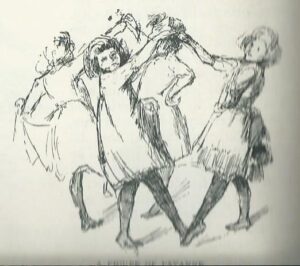

I like the way that Rose le Quesne’s impromptu sketch has the young dancer dancing right out of the frame

The reporter then turned his attention to Mr D’Auban, who taught young female dancers who worked at the Lyric, Drury Lane and Prince of Wales West End theatres. His general impression was that the girls find dancing ‘a pure pleasure.’ Many of them come from ‘stage’ families and had been involved in the theatre since they were babies. There were no apprenticeships here: ‘Mr D’Auban has no agreements with parents and no charges, and he says that he can make any child of fair intelligence a good dancer in six months.’ But the School Board ‘only allows them to attend the class two days a week – and they then go home and practice the ballet positions, the chassés, the pirouettes and all the rest of the movements’ by themselves.

The girls practice a Pavanne, a stately 17th century Spanish dance

‘Mr D’Auban gives the example of eleven-year-old Minnie Burley who, for more than a year, has supported herself and her crippled mother, earning £1.5.0 a week, and, when that ended, only 12 shillings a week. But poor Minnie is worried about what will happen when the engagement ends. She comes home, alone, from the Strand Theatre, late at night.’ Wasn’t her mother worried?

A very young dancer, her skirt held just so

‘No,’ said Mrs Burley, ‘she comes by bus, and she knows how to take care of herself – she knows she is not to let anyone talk to her.’ To modern ears, poor Minnie’s position sounds very worrying. But the girls themselves don’t see it like that. They are ‘immensely proud’ of helping their mothers. ‘One small girl ran after me the whole length of the street. She reached me breathless, saying, “Don’t forget, I’m principal butterfly!”‘’

First steps. This looks like a girl who might, in time, become a ‘principal butterfly!’

The girls’ wages ranged from 6 to 16 shillings a week, and their engagements usually lasted about four months – I noted that they were paid far less than the boys were for their acrobatics.

I wonder where this was – the girls are all dressed the same – could it be a swing on stage? I don’t think they had public playgrounds with swings at this date.

It is good to know that there was time to play – and I don’t suppose the little girls had a lot of free time. They would probably be called on to do a number of tasks once they’d got home: sewing, looking after a baby brother or sister, and, of course, practicing their steps.

At tea

At least Mr D’Aubun saw to it that they were fed, perhaps after the class was over. It might well be the one proper meal they got during the day. Perhaps they all have to snuggle up together to keep warm. At all events, they look contented with their lot.

I hope you have enjoyed this glimpse into The Strand Magazine’s popular reading during the late Victorian Age.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Very interesting. I love the illustrations of the young acrobats.

Thank you, Jan. I, too, loved the illustrations – a far cry from the winsome, over-angelic-looking children one so often sees in Victorian pictures.

A very interesting look at life how it was for children. I can’t help but think of the modern kids with their skateboards, climbing frames and whatnot. Kids are so agile, I don’t find it surprising that they were able to learn how to be acrobats and dancers. Perhaps we take a rather unrealistic view of childhood these days? Children like to contribute, don’t they? Helping with tasks in the house – that is, if you can get them off their mobile phones! Frankly, I’m not sure these kids doing healthful exercise (as long as they were fed well and given an education too) were not better off in some respects than our screen-glued children today.

That’s a very interesting point of view, Elizabeth. The little girl from a theatre dance troupe, who was proud of being able to help support her family financially, grew up with a realistic grasp of the difficulties of being poor. I think the boy acrobats were even better off – at least they could earn a decent living when they grew up – provided, as their teacher said – that they kept off the bottle. Alcohol and acrobatics did not go well together!

fascinating

and the drawings are marvelous

I’m glad you liked the drawings, too, Jess. It’s unusual to find rough sketches in a 19th century article instead of carefully finished drawings, but I think these really work. You get much more of an impression of what the children’s lives were really like – the boy throwing knives has his braces showing, for example!

Magazines certainly have changed a lot since their inception, haven’t they? I am very surprised to see that they were once hardbacks.

It’s difficult to imagine a magazine nowadays writing an unbiased article with the intention of leaving the reader to come to their own conclusions; imagine that!

There must be quite a strong temptation to be a bit nostalgic when writing about this kind of thing. I think you navigated the issue very well, as usual.

Thank you for your comment, Huon. The 6-monthly hardback edition of The Strand is more like the Annual edition of the most popular bits that one used to get with the classier children’s comics in the 50s and 60s e.g. Eagle, which featured Dan Dare. I don’t think you would bother to get the hardback edition as well as the monthly mag. unless you really enjoyed the magazine and knew that you wanted to re-read it.

Don’t forget that all of Dickens’ novels were first published in monthly magazines over, perhaps, eighteen months, as were the novels of most Victorian novelists, e.g. Mrs Gaskell, W M Thackeray, Anthony Trollope and others. The complete book would only be published once the monthly episodes had come out.