I have long been fascinated by the Victorian age. It was a time of huge contrasts, as well as social mobility- certainly for men. But what about women? At the beginning of the Victorian age, they had no legal existence, they couldn’t vote, nor have a bank account, and what work opportunities they had, in factories or shops, say, were were less well-paid than men. As for any more professional position – forget it. The choice of jobs for most middle-class women was being a governess or lady’s companion for, at most, about £35 a year, or, for a few talented writers, actresses, artists or musicians, you might be able to make a decent living, if your father or family were also in the same profession.

However, there was an alternative – a shocking one; become a mistress.

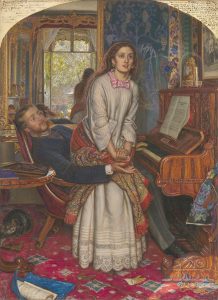

Today, I’m looking at the life of a mistress of a middle-class man in the 1850s, and, fortunately, there is exactly the right picture to illuminate this: the pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854.

The picture shows an actual room in a maison de convenance – the traditional place for Victorian gentlemen to house a mistress. So, if you’ve ever wanted to see exactly what such a room looked like, this is the real thing: Woodbine Villa, 7 Alpha Place, St John’s Wood, so be specific. I looked it up in the London Topographical Society’s A to Z of Victorian London and, whilst it’s not a fashionable address, it must have been a pleasant place to live. Woodbine Villa was a detached house, within five minutes’ walk of the Royal Botanic Society’s Gardens in Regent’s Park, near Baker Street and Marylebone railway stations, and the Oxford Street shops were not too far away. Perfect for a mistress with a generous allowance from her lover, and easily accessible for her protector.

The new, but garish, carpet is already coming unravelled.

Let’s start by looking at the room which shrieked ‘nouveau-riche vulgarity’ – to the original viewers, who were shocked to see a picture so in-your-face modern. The garish patterned carpet is new (though a bit of the carpet is significantly unravelling in the bottom right-hand corner). The heavily-ornamented rosewood piano is too shiny. Everything in it speaks of a room which is newly-furnished for a mistress; it is not, and never could be, a family home. There is no vase of flowers picked from the garden by the lady of the house. No small boy plays with his toy soldiers on the floor.

Hunt wants you to notice the symbols of a guilty relationship. The heavily-gilded clock on the piano top is under a glass dome, perhaps emphasising the relationship of the young woman to the man; she, too, is kept under glass, as it were. She is not part of the man’s ordinary life. His parents (or, perhaps, even his wife) do not even know she exists. We note his tall top hat on the table – one might call it phallic – and a glove dropped carelessly on the floor is evidence of a fleeting visit. We can tell that he is a fashionable young man by his curly hair and full side-whiskers.

A cat hides under the table to the left. He (it is surely a tom) has caught a pretty bird alive and is playing with it, just as the man plays with the girl.

The girl herself is wearing a night-dress with a brightly-coloured shawl wrapped round her waist. My Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century tells me that: Shawls with centres of a brilliant colour contrasting with the borders were much worn. She is also wearing large hoop earrings, also very fashionable. The gentleman has obviously spared no expense either with regard to her clothes, or the accommodation. Her hair is loose which indicates the familiarity of their relationship. Furthermore, just in case we have missed the point, she is not wearing a wedding ring.

What Holman Hunt’s painting shows is the very moment of the girl’s spiritual awakening to her moral degradation. Her lover has been playing the piano – one hand still rests on the keyboard. He plays Thomas Moore’s Oft in the Stilly Night, a plaintive song which recalls lost opportunities and happiness in the past.

Oft in the Stilly Night,

Ere Slumber’s chain has bound me

Fond Memory brings the light

Of other days around me…

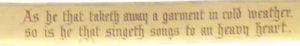

Biblical quote from Proverbs

But there is more. The bottom of the picture frame has a quote from the Bible, Proverbs 25.20: As he that taketh away a garment in cold weather, so is he that singeth songs to a heavy heart. This didn’t make much sense, so I found a modern translation. It said: Like one who dresses a wound with vinegar, so is the sweetest of singers to the heavy-hearted. This made more sense; the man thinks he’s simply playing a sentimental song but the girl herself is reacting to the poignant and painful memories the song evokes. Suddenly, we can see, she wants out. She makes to stand up, but he can very easily pull her back down onto his lap. The viewer is left not knowing what happens.

As the social journalist, Henry Mayhew (1812-1887) made clear in his London Labour and the London Poor, it was all too common for a young girl fresh from the country, to find herself cozened by a procuress and ending up either in a brothel or as some man’s mistress. A life of disease, poverty and the dreaded workhouse awaits her. Or does it?

Perhaps she has not made such a foolish choice, after all. She is attractive and intelligent and he is fond. Maybe she can have her cake and eat it.

However, one has to say that, so far, the girl in the picture has done rather well for herself. Her lover is rich and fond; he might be persuaded to secure an annuity on her. She could be sensible and avoid alcoholism (common among prostitutes) and save for a rainy day. (Unfortunately, the Post Office Savings Bank will not open until 1861 but that date is not too far away.) If she’s a country girl, she might well doubt her welcome back home. And what other options are open to a reformed lady of easy virtue? Does she really want to live in poverty on a pittance doing sewing, and end up in the workhouse? The price of virtue might just be too heavy.

She might even have noticed that this picture is not aimed at the man who tempted her into vice. Hunt is concerned only about female sexual virtue. Maybe she will opt for a different solution from the one Hunt is urging her to take.

In reality, many women like the girl above returned to a more or less regular way of life. It depended if she succumbed to the lure of drink and gambling, as so many ‘fallen women’ did. However, if her lover were generous and gave her a few hundred pounds when they parted, she might buy a small shop, say, and support herself pretty well.

If you want to see the picture and decide for yourself, The Awakening Conscience by William Holman Hunt is in Tate Britain.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

It’s a fascinating study. In fact, from my research, this girl is a great deal better of than the average prostitute. She is well housed, probably has a maid to do the housework, and doesn’t have to pander to her protector all day and every day. I often think mistresses were better off than wives, given a rich lover. When one affair ended, she might well be taken up by another protector, or even passed on. The only trouble is when the beauty fades. As you say, then she needs to have saved enough to support herself with some business or other. Some canny high-flyers became madams in their own bawdy house. Better this perhaps than a listing in Harris’s little black book and thereby taking on whatever clients chose to visit!

Of course, the Victorians were bound to concern themselves with the moral question. Talk to the man, I say!

I agree with you, Elizabeth, the young girl in the painting looks just fine – at the moment, at any rate. I think her future would depend on how canny she is. With a bit of intelligence and nous, I think she could probably work the system. Her protector doesn’t look over-burdened with intelligence to me; if she were clever, she could persuade him to give he a decent sum when they parted so that she could save for her future. Property never goes amiss.

And I note that Holman Hunt is only concerned about her moral state; men could obviously behave as they pleased.