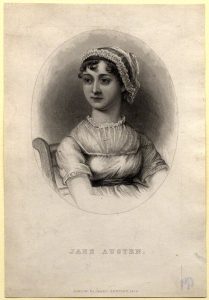

General Tilney is surely one of the most unpleasant characters Jane Austen ever created. He’s greedy, hypocritical and a bully. But it is through him that Jane Austen’s naïve eighteen-year-old heroine, Catherine Morland, learns a number of important lessons about human nature.

When Catherine first sees him in the Assembly Rooms she is standing beside Henry Tilney – a man she has recently met and finds very attractive. She notices that she is being ‘earnestly regarded by a gentleman…immediately behind her. He was a very handsome man, of a commanding aspect, past the bloom, but not past the vigour, of life.’ He learns forward and whispers something to Mr Tilney.

Catherine, who is not used to Society, is embarrassed by the gentleman whispering. Is there something wrong with her appearance? Then Henry says: ‘That gentleman knows your name and you have a right to know his. It is General Tilney, my father.’

It the first time that General Tilney’s attentions make Catherine feel uncomfortable, but it won’t be the last. What she doesn’t know is that the obnoxious John Thorpe, the brother of her friend Isabella, has been telling the General lies about her station in life: that she has a dowry of between £15-20,000, and she is the heiress of the wealthy Allens, whose guest she is.

The General is immediately determined that Catherine will marry his younger son, the Reverend Henry Tilney. He invites Catherine to stay with them at Northanger Abbey.

His invitation (he goes on for twenty-three lines) is a mixture of boasting and fulsome flattery. He tries to impress her with name-dropping; he had hoped to see ‘the Marquess of Longtown and General Courteney, some of my very old friends here’ and then asks her if she could ‘be prevailed upon to quit this scene of public triumph, and oblige your friend Eleanor (his daughter) with your company in Gloucestershire.’ He ends, with hypocritical modesty: his ‘mode of living is plain and unpretending; yet no endeavour shall be wanting on our side to make Northanger Abbey not wholly disagreeable.’

His use of litotes (‘not wholly disagreeable’) is ironic, and makes it clear that, in fact, he rates the attractions of Northanger Abbey very highly. The whole speech is way over the top and, not unnaturally, Catherine is overwhelmed. ‘To receive so flattering an invitation! To have her company so warmly solicited!’ She takes it all at face value.

But, even as the carriage sets off for Northanger Abbey, Catherine begins to feel uneasy about his constant attention. Is she comfortable? He stops for lunch at an inn and bullies the waiters with impossible demands. He’s very fussy about his food and the ‘short’ stop takes over two hours. What would Catherine like to eat? He fears that he’s offered her nothing to her taste, when she’s never seen such a variety of food in her life before. In any case, they had a substantial breakfast before they set out and she’s not hungry. He makes ‘it impossible for her to forget for a moment that she is a visitor’.

The truth is that the general is a bully who manipulates Catherine into praising everything she sees, whether she likes it or not. Jane Austen leaves us in no doubt that General Tilney fails, both as a host and as a man, because he’s not interested in his guest’s comfort. He only wants to hear praise of himself and his possessions.

It gets worse once they reach Northanger Abbey. Catherine, whose passion is reading Gothic novels, is longing to see the ancient parts of the abbey but the General, having offered her a choice of seeing the house or grounds, says: ‘Yes, he could certainly read in Miss Morland’s eyes a judicious desire of making use of the present smiling weather. But when did she judge amiss? The Abbey would always be safe and dry.’ He has manipulated her into doing what he wants.

Poor Catherine! ‘She was all impatience to see the house, and had scarcely any curiosity to see the grounds.’ She ‘put on her bonnet in patient discontent.’ (A wonderful phrase which perfectly describes her feelings) The tour is a nightmare. The General hopes to learn that the Allens’ estate is inferior to his own. All Catherine can say of what she’s shown: ‘It was very noble – very grand – very charming!’ over and over again. It scarcely matters; General Tilney supplies his own praise.

One of the lessons Catherine must learn, both with regard to her friend Isabella and with General Tilney, is that people can say one thing but mean something quite different. She has already been confused by Isabella falling in love with her brother James, becoming engaged to him, and then encouraging the attentions of Frederick Tilney, Henry’s older brother (a far better marriage prospect). Duplicity isn’t in Catherine’s nature and she doesn’t understand why people behave dishonestly.

When the General arranges for them to visit Henry’s home at Woodston Parsonage, he insists: ‘You are not to put yourself at all out of your way. Whatever you may happen to have in the house will be enough. I think I can answer for the young ladies making allowance for a bachelor’s table.’

Catherine believes him. But Henry knows better, and leaves Northanger Abbey early in order to prepare a suitably elaborate meal.

Catherine exclaims: ‘But how can you think of such a thing after what the General said? When he so particularly desired you not to give yourself any trouble, because anything would do.’

Henry smiles but still leaves early for Woodston.

Afterwards, Catherine finds herself pondering on the General’s inexplicability: That he was very particular in his eating, she had, by her own unassisted observation, already discovered; but why he should say one thing so positively; and mean another all the while, was most unaccountable! How were people, at that rate, to be understood?

What is interesting here is that, for the first time, Catherine is discovering things ‘by her own unassisted observation’. Not only has she has stopped taking everybody on trust – Isabella has been using both James and herself – she has stopped living in her Gothic fantasy world; General Tilney has neither incarcerated his wife nor murdered her. But both Isabella and the General alter the truth to suit themselves.

Catherine is beginning to judge people for herself; and she is shortly going to need her new-found emotional intelligence. And, I would argue, the obnoxious General Tilney was, perhaps, the most important instrument in her maturation.

Photos of Powis Castle, Dunham Massey and Lyme Park, and Kew Palace bedroom standing in for Northanger Abbey by Elizabeth Hawksley.

Elizabeth Hawksley.

Please share this page...

Very interesting, and of course true. A dual-purpose character. (Love the illustrations!)

Thank you, Jan. I’m glad you enjoyed the photos, as well. It’s not easy to find appropriate illustrations for ‘Northanger Abbey’. I even went to the National Portrait Gallery to see if I could find a ‘General Tilney’. I found a portrait of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. His portrait looked OK as far as age, pride and a bit of bluster went, but it was too obviously royal.

A long time since I’ve read it, but you’ve inspired me to look at it again. The opening paragraphs, as I remember, are a hoot. But I hadn’t recalled all these details about General Tilney, though do remember he was a bit of a beast, especially when he finds out the truth. A nicely reasoned piece, Elizabeth.

Thank you, Elizabeth. I remember reading my 16-year-old daughter the chapter where Catherine is desperately trying to avoid the obnoxious John Thorpe in the Assembly Rooms, in case he asks her to dance, and my daughter laughing so much she fell off the chair! I think it’s a book where different things strike you at different ages.