In my opinion, Faro’s Daughter is probably Georgette Heyer’s most emotionally intense book. The relationship between the hero, the cold, rude, fabulously rich Max Ravenscar and the beautiful Deborah Grantham who presides over a gaming establishment in St James’s Square in the heart of fashionable London in the 1790s, has a sexual tension which is quite unlike any of her other books.

Georgette Heyer by Howard Coster 1939

Some of the story’s heightened emotion may be due to the fact that it was written in 1941, at the beginning of the Blitz when German bombers crossed the channel nightly to bomb British targets. Georgette Heyer was living in Hove, a seaside town on the Sussex coast – alone for much of the time. And towns along Britain’s south-east coast were the Luftwaffe’s nearest target on leaving their airbases on the Continent; Hove was bombed heavily.

Her husband, Ronald Rougier, had just been called to the Bar and had begun to commute daily to London – a train journey which exposed him to Luftwaffe raids – trains and railway stations being prime Nazi targets. Their son, age 8, had just gone to a boys’ prep boarding school, and, during term time, Georgette was alone. Naturally, she did her bit for the war effort, fire-watching by night, keeping her eyes peeled for approaching bombers and where they were heading. It must have been an immensely stressful experience. We, too, have been living under constant stress over the last eighteen months, and we know how much we need books like Georgette Heyer’s to take our mind off what’s going on around us.

What struck me, particularly re-reading Faro’s Daughter, was the intensity of emotion – often ignored and/or denied by both Ravenscar and Deborah, and I wondered if Heyer had used writing Faro’s Daughter as a way of blotting out the Battle of Britain raging overhead night after night and something of that terrible experience percolated through Faro’s Daughter, the book she was currently writing.

When Ravenscar first appears on page 1, he is described as being very tall, with good legs, broad shoulders, a lean, harsh-featured countenance, an uncompromising mouth and extremely hard grey eyes. His hair is cut very short – which at the time (1790s) was still shocking – society was used to powdered hair. I have to admit that my first thought was – Wow! Heyer instantly yanks her female readers into a much more interesting place – far away from bombs or pandemics.

Max’s aunt, Lady Mablethorpe, warns him that his ward and nephew, the 20-year-old Adrian, who will shortly inherit a fortune, has fallen in love with ‘a wench from a gaming-house’ and intends to marry her. His aunt calls her ‘a bold, vulgar piece’, she further warns him that ‘they say the girl is like a honey-pot…’

Heyer then tells us a bit more about Max, and we learn that he enjoys boxing and cock-fighting; he’s an excellent rider; and he has very little interest in women, the last of which I found worrying. He doesn’t have mistresses, though his name is occasionally coupled with ‘ladies of easier virtue’ which sounds as if he goes for older married ladies who enjoy sex but prefer their extra-marital canters to be kept quiet.

On the other hand, he plainly has a good relationship with young Adrian and with his 18-year-old half-sister, Arabella.

In Chapter 2 we meet the heroine, Deborah Grantham, the Faro’s Daughter of the title who works in a high class gaming house. This is how we – and Ravenscar – first see her:

‘a tall young woman with chestnut hair glowing in the candle-light, and a pair of laughing dark eyes, set under slim arched brows. Her luxuriant hair was quite simply dressed, without powder, being piled up on top of her head, and allowed to fall in thick, smooth curls. One of these had slipped forward, as she bent over the table, and lay against her white breast.’

And Ravenscar’s reaction is interesting: he had no difficulty at all in understanding why his young relative had so lamentably lost his head.

Max’s reaction is immediate and visceral. This is what he thinks: The lady’s eyes were the most brilliant and expressive he had ever seen. Their effect upon an impressionable youth would, he thought, be most destructive. As a connoisseur of female charms, he could not but approve of the picture Miss Grantham presented. She was built on queenly lines, carried her head well, and possessed a pretty wrist and a neatly-turned ankle. She looked to have a good deal of humour, and her voice, when she spoke, was low-pitched and pleasing.

Hm. We are allowed to ask a few questions. Ravenscar thinks of himself as being ‘a connoisseur of female charms’ but we know that this is far from being the truth. We also note that he sees a woman’s relationship with a man as usually ‘destructive’. And he has assured his aunt that: There is not the slightest need for you to concern yourself about me, ma-am. I am neither twenty years of age, nor of a romantic disposition.’ His aunt tells us that he is ‘indifferent to women.’

I began to suspect that Max had serious unfinished business with regard to his relationships with women – worryingly, he swallows everything Deborah’s ill-wishers say about her, as being true – even if, like his aunt, they have never even met her. It is all hearsay. And we notice that her reputation immediately clashes with the effect she actually has on him; it’s obvious to the reader that Max finds Deborah seriously sexually attractive the moment he meets her – but he is not admitting it – even to himself. And he instantly puts the worst construction on Deborah’s relationships with various members of her household. She is furious when she hears that Adrian knows about her aunt being in debt. Max interprets this as a lie: he decides that she must have cleverly persuaded Kennet (a family friend) to tell Adrian about the unsavoury Lord Ormskirk who has unscrupulously bought various bills and the gaming house mortgage from Deborah’s aunt, Lady Bellingham, valued at a staggering £6,500, in order to get Adrian’s sympathy. Ormskirk, we realize, wants Deborah for his mistress.

Ravenscar will never grow up emotionally until he can question the truth of what he’s being told about Deborah and make up his own mind.

Deborah’s own reaction to meeting Ravenscar is also interesting. When asked by her aunt if Ravenscar liked her, could only say: I don’t know. He’s a strange creature. I had the oddest feeling that he didn’t like me, but he chose to play with me all evening …’

Lady Bellingham instantly wonders if Mr Ravenscar has taken a fancy to her niece. Deborah denies it – but the question is left unanswered. But a few lines further on, she hotly defends Mr Ravenscar against the charge of being as odious as the horrible Sir James Filey.

Lady Bellingham then exclaims: ‘Deb, never say that you have taken a fancy to Ravenscar!’ Deborah denies it but adds that ‘there was something about him that was different from all those other men…’

To her surprise, Ravenscar appears the following day and invites Deborah to drive round the park with him. ‘She was conscious of a strong inclination to go with him.’ It’s the sort of request that a man might make when he’s interested in a woman. He admits that he wants to be private with her – and Deborah became aware of a most odd sensation, as though an obstruction had leapt suddenly into her throat on purpose to choke her. Her knees felt unaccountably weak, and she knew that she was blushing. But you barely know me! ‘ she managed to say.

Deborah at least is aware of her feelings – and she dresses carefully, hoping that Mr Ravenscar will think that she does him credit. Alas, ‘being private’ with Deborah carries no romantic connotations for Ravenscar – or none that he admits.

Georgette Heyer’s birthplace, Wimbledon

When he offers to help her out of her financial difficulties, she fears that he’s going to ask her to become his mistress but it’s even worse. He offers to pay her £5000 to renounce any thought of marrying his nephew Adrian. Deborah is furious – she’d never considered marrying Adrian in the first place. And she resolves to punish Ravenscar for daring to think that she’s the sort of woman who would ruin a twenty-year-old young man out of greed. (She herself is twenty-five.) She is now determined to play up to Ravenscar’s worst fears. And the reader can tell that she is both disappointed and furious at having misread his signals.

She starts by encouraging Adrian, allowing him to think that she will marry him after all and saying that it’s fine if he wants to tell his uncle – Mr Ravenscar. But, although she is tempted to smash Adrian’s love and respect for Ravenscar by telling the young man how Ravenscar has treated her, she doesn’t do so. It’s a step too far.

Max begins to ‘struggle with the first tiny shoots of … doubt.’ When he tells his aunt of his encounter with Deborah, something makes that lady say, ‘Do not tell me that she has got you under her odious spell?’ Max denies it hotly.

Gradually, as the plot unfolds, other characters begin to have their suspicions that Deborah may be in love with Max. After the episode where Ravenscar is locked in the Lady Bellingham’s cellar and Deb lets him out after he has scorched the back of his hands with a candle she left in the cellar and managed to free himself, Kennet exclaims, ‘it’s my belief that it’s more than half in love with the man you are, Deb!’ She denies it.

Things begin to move for Ravenscar, too. He gradually realizes that Deborah is not a fortune-hunter and never had any intention of marrying his nephew. Ravenscar has acquired Lady Bellingham’s bills and mortgage from the repellent Lord Ormskirk in a game of piquet, and he returns them to Deborah with a card simply saying, ‘With my compliments.’

This is a momentous step: Ravenscar – the man who is notoriously mean with money – is, for the first time, being generous – and there are no strings attached to his gift.

When Kennet hears of it, he tells Lady Bellingham, ‘I’d a strong notion that our friend was a deal more taken up with Deb’s charms than she guessed.’ Later, he thinks that ‘Deb, too, is more than half in love with the fellow.’

And then Adrian, who in the meantime has fallen in love with the very young Phoebe, reappears telling him, ecstatically, that he’s a married man! Ravenscar instantly jumps to the conclusion that Adrian has married Deborah, and storms off to St James’s Square, collars Deborah, and unleashes all the anger, contempt, and bitterness he feels. He’d thought he’d come to love her, he tells her, and she could have had his money and his name, if she hadn’t behaved like a harpy.

Deborah is furious: ‘You will be sorry you ever dared to speak to me in those terms!’ she tells him…. ‘Marry you? I would rather die in the worst agony you could conceive. Don’t dare – don’t dare to enter this house again!’

I came to the conclusion that Max had never had to cope with the torments of adolescent love. His father had died when he was a very young man, which made Max immensely rich and able to do anything he wanted. He’d never experienced painful love tangles, or been tormented by jealousy or rage – and he was totally unprepared for the rage and jealousy he felt when he thought that Deborah had double-crossed him.

In a splendid scene, we find him in his library, pacing up and down ‘a prey to the most violent and confused emotions he had ever experienced.’ He wants to throttle his nephew, Adrian (who he thinks has married Deborah); to strangle Deborah and throw her body to the dogs (like Jezebel), and he ‘smashes a Sèvres figure which he had always detested which some nameless fool had dared to place upon the mantelpiece.’ At this point, emotionally, Max is about sixteen; and the reader realizes that he should have experienced all these adolescent agonies twenty years earlier – he is now thirty-five.

Max ends the evening by visiting his aunt to commiserate with her about her son Adrian’s misalliance with Deborah, and to apologise for not having put a stop to it. There he learns that Adrian has not, in fact, married Deborah. He has married an eighteen-year-old debutante Phoebe, whom he earlier rescued from the creepy Sir James Riley. Phoebe has fled her family and was staying with Deborah and her aunt.

‘My God, my God, what have I done?’ burst from Mr Ravenscar. He sprang to his feet, and began to pace about the room as though he could not be still another instant. He’s reverted to being sixteen.

There are more emotional outbursts in store for Ravenscar – and for Deborah. And we notice that even though Deborah throws him out again when he tries to apologize, she returns the bills and mortgage to him; which allows him to return them, torn up – Ravenscar has at last acquired a bit of adult nous and left a door open. Then Kennet attempts to kidnap Ravenscar’s half-sister, and leaves a letter for Deborah telling her. Desperately concerned, she takes the letter to Ravenscar’s house….

This time, the lovers have caught up with themselves; they have both learnt to express their real feelings, and the ending is perfect.

It is the only book where Georgette Heyer allows her hero to get things so spectacularly wrong and to go through so much agony of mind – on stage. We may have the Luftwaffe to thank for that.

© Elizabeth Hawksley

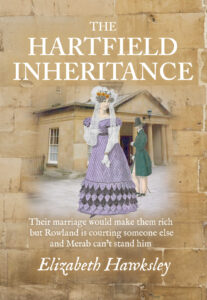

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B09HNX5KF3

Please share this page...

I love the psychological deductions which you make here, Elizabeth – I hadn’t matched Georgette Heyer’s state of mind to the novel – fascinating – and it rings true that Max had never had the time for the sheer fever and confusion of teenage love.

What a splendidly reasoned blog. I have always loved Faro’s Daughter, but I’d never thought it might be because we see the hero growing emotionally. The scene where Deb goes down to free Ravenscar from the cellar “because it wasn’t playing fair” remains one of my favourite ways GH showed character obliquely.

Thank you for your comment, Jan. I agree with you that the scene with Ravenscar and Deb in the cellar is brilliant.

Love this book. Your reasoning is very interesting. I’d never thought of Max in those terms. I have to say, though, that my favourite scenes are those with Aunt Lizzy, who is the funniest character in the canon for me. Her confusion over what Deb does is hilarious. “Don’t show him anything more, Deb! You see what has come of showing him things.” And at the end, when she collapses as “one past human succour”. Priceless.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. Poor Aunt Lizzy! She just doesn’t get it! But she does pick up that Ravenscar and her niece are interested in each other – so she’s not entirely clueless!

Thanks so much for this interesting post, Elizabeth. Faro’s Daughter is one of my favourite Heyer novels. I hadn’t thought about the terrible time in which she was writing it, and how this may have affected the story. I totally agree about the sexual tension. The exchanges between Deborah and Ravenscar are brilliant, and I love how she outwits him. Now I’d like to read the book yet again.

Good to hear from you, Helena. I hope you are keeping well. I came across a comment about Heyer living alone in Hove during the first part of the war and I started to wonder if, and how it might have affected her writing. And the more I thought about it, the more I thought – of course it affected her. Heaven knows, we have all been affected by the pandemic – I couldn’t believe that Heyer would have just sailed through the war; there were bombs dropping for heaven’s sake!

Max is unusual in that he has a really rough time emotionally – followed by an epiphany! That must come from somewhere.

Wonderful! I really must make the time for more books like these.

I think you might enjoy Georgette Heyer: if you are ever feeling ill, down, or fed up with things, they are great at cheering you up and making you laugh¬