Re-reading Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice recently, I found myself wondering why everyone in the Lucas family, calls Elizabeth Bennet ‘Eliza’, rather than ‘Lizzy’, which is what her family call her. Is she a slightly different person when she is ‘Eliza’? And why is she Charlotte Lucas’s ‘intimate friend’, anyway? Jane Austen describes Charlotte as, ‘a sensible, intelligent young woman, about twenty-seven’. Elizabeth is twenty, and we know that she has a close relationship with her twenty-two-year-old sister Jane. Normally, at twenty, one’s friends tend to be one’s own age, for example, Kitty Bennet is a close friend of Charlotte’s sister, Maria, who is more or less her own age, so we are allowed to ask what Elizabeth gets from her friendship with Charlotte that she doesn’t get from Jane.

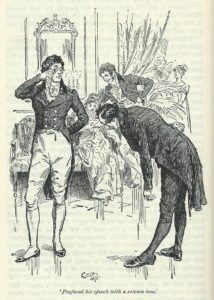

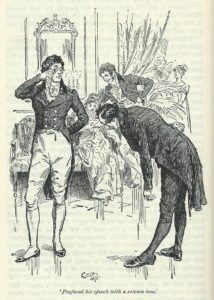

Mr Collins accosting Mr Darcy at the Netherfield Ball by Charles E Brock

Continue reading Jane Austen: The Enterprising Miss Lucas

Please share this page...