Socialist Realism Art (promoted by the Stalinist Communist leader, Enver Hoxha until his death in 1992) is not to everyone’s taste but it does give a fascinating insight into what was going on in Albania, or perhaps more accurately, how Hoxha’s Communist Party wanted and, perhaps, needed Albanians to see themselves.

Dealing with a blockage.

Above, we can see that fiery sparks are shooting out of a malfunctioning machine on the right; a man is struggling to unblock it. The vivid orange safety clothing and the worksite’s obvious heat makes the place look like an inferno. It must be incredibly dangerous work; the Communist Party’s national story has it that these men are Albanian Communist Party heroes.

*

However, let’s start at the beginning. 19th century Albania was part of a weakening Ottoman Empire ruled with a rod of iron by the Turks, and, not unnaturally, the Albanians wanted their independence. There were a number of fierce uprisings, and Albania finally gained its independence in 1912 – but the timing was unfortunate and there was little opportunity to plan for the future. The Balkans erupted into war in 1914, which rapidly engulfed Europe and then much of Asia. Albania found itself struggling against its neighbours, all of whom had their own interests in mind with regard to Albania’s future. However, a small Albanian state was eventually recognized by the post war peace talks and the newly-independent country was led by Ahmed Zog, first, as President and then self-promoted to King from 1928-39.

In 1939, World War II broke out and Italian troops of the fascist Mussolini, who had been eyeing up Albania for some time, invaded.

Attacking the enemy with a cannon, 18th October, 1944 by Petro Kokushta (1979). Note the young man on the right picking up the next shell to be loaded.

The painting above depicts the Albanian Communist Partisans’ attack on a treacherous Albanian ‘Nationalist’ Assembly which was hosting a meeting with German Nazis on 18th October 1944. The partisans suspected – probably rightly – that Albania was in imminent danger of being swallowed up by Nazi Germany.

A section of the 3rd Partisan Brigade has dragged a cannon up onto the hills above Tirana, and the cannon is firing down on the Victor Emmanuel III Palace seen amid the smoke in the background where the meeting is taking place.

*

During the Second World War the Albanians found themselves fighting on two fronts: against the fascist Italians on the one hand, and the Nazi Germans on the other. When the Albanian Communist Party was founded in 1941, it looked to the Soviet Union for help. But Albania was only finally liberated in November 1944 when Enver Hoxha (pronounced Hod-ja) came to power and set up a Stalinist Communist regime.

Vilson Kilica’s painting below shows Hoxha returning from his crucial meeting with the other Communist countries, having secured a peaceful settlement from his Communist neighbours. He is greeted as a hero.

Declaration of the Republic in Tirana, 1944 by Vilson Kilica, (1982-3)

Enver Hoxha, wearing a long grey overcoat, salutes the crowd. A bride has come out with her new husband to welcome him; a small girl, holding white flowers, is, one suspects, about to cast them at Hoxha’s feet. The banner on the right reads ‘Glory to the Party of Labour – Albania’. A respectable working woman, spreads her arms in reverence. The painting depicts Hoxha as the people’s Saviour. It could almost be a modern Jesus entering Jerusalem in triumph.

However, we note that it is an historical painting from 1982-3 depicting an event which happened nearly forty years earlier. We are allowed to ask: was it really like that?

Hoxha’s rule was a brutal mixture of back-breaking labour; massive industrial development; and the systematic crushing of opposition. He depended on the financial help of a number of communist allies: Tito’s Yugoslavia until 1948; Stalin and Khrushchev’s Soviet Union until 1961, and Mao’s China until 1975. Albania then found itself isolated and Hoxha instituted a new slogan ‘self-reliance’, and Albania withdrew into a disastrous isolation.

Students were co-opted as ‘Aktionists’ doing ‘voluntary’ labour for the glorification of the Communist Party. A painting by Rafael Dembo shows a line of young people setting off to work – the girls carrying pick-axes over their shoulders, young men with spades.

When I went to Albania in 2015, we travelled mainly by coach. One day, our Albanian guide stopped the coach; he wanted us to see a railway line, almost overgrown under weeds and grass. We all got out. ‘I helped to build that line,’ he said, flatly. ‘We had to. It was our ‘voluntary labour’. They never gave us enough to eat.’ He went on to tell us that they built it by hand, with only picks and shovels. His deliberately matter of fact tone, spoke volumes.

With no more foreign investment coming in after 1975, the country’s infrastructure rapidly fell apart. After Hoxha’s death in 1992, the communist party staggered on for a few years and then more or less imploded when the population turned against anything which symbolized Hoxha’s rule and destroyed it. The paintings gathered dust in forgotten galleries.

Albania adopted western-style capitalism and the huge task of reconstruction began.

Raising Pylons.

Now the paintings are back on show, and we can see what the Communist Party of Albania was trying to promote.

For the very first time, the people of Albania will have the blessings of electricity to heat and light their homes, is the message here. Back in England in the 1930s, the poet Stephen Spender also found the bringing of electricity to rural England excitingly modern and liberating. He compared pylons to ‘nude giant girls striding the landscape‘. I’m not sure that Hoxja would have approved.

However, one thing that Hoxha must be given credit for is giving women the vote and allowing them to train for and take professional jobs. The young woman in the Raising Pylons picture is holding what looks like plans for the site behind her. The man accepts her authority. In the 19th century, Albanian women were probably the least liberated in Europe; they had no rights whatsoever, and they did most of the work. The Socialist Realism pictures include a number of paintings showing women having a professional role in the building of a new world.

I knew, from my reading about the traveller Edith Durham’s adventures in early 20th century Albania, that the Albanians had been heavily oppressed by their Turkish overlords and that the country was still in a state of almost Medieval poverty; farms were worked by hand, with oxen. I have a large World Atlas from 1897 and Albania doesn’t yet exist – it is still part of Turkey. There are no railways, and few marked roads.

When it finally came into existence, Albania was the only European country not to have a standard rail service. A few narrow gauge lines were built during the First World War to access the mines and for military purposes, but that was it. Goods were carried by horses or mules. Carts were of limited use as proper road surfaces were non-existent and country roads were full of mud in winter and pot-holes in summer. People travelled on foot or on horseback.

It was Hodja, in 1947, who vowed to build a proper rail network.

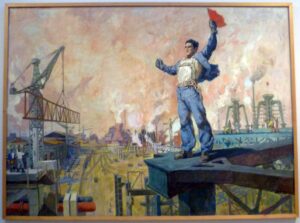

The Assembler by Petro Kokushka, (1979) ‘The worker at the top of everything and this one is waving a red flag’’

If you look carefully, you can see that the young man standing, legs apart, holding the red flag with the black eagle of Albania aloft, is hundreds of feet up on a massive iron frame – part of a building in the process of being erected. He’s wearing a harness but he has no other safety equipment. None of the workers beneath him are wearing hard hats, for example, and scaffolding seems to be unknown.

This is how Hoxha wanted young Albanian men to see themselves. ‘The worker at the top of everything and this one is waving a red flag’ as the caption has it. And he certainly doesn’t suffer from vertigo. It is young men like this whom the Communist Party of Albania is most proud.

To prepare the land for the construction of Collective and State Farms after the Agricultural Reforms of 1969 would also have needed an enormous amount of hard physical labour – as elsewhere.

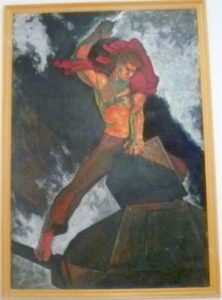

‘Vojo Kushi’ by Sali Shijaku, (1969)

There are some vivid pictures of heroes of the revolution. One of the most famous pictures shows a real-life incident during World War II. Vojo Kushi, a young Partisan, found himself, with two other comrades, in a house in Tirana surrounded by Italian fascists. With incredible bravery, they rushed towards the enemy, and Vojo leapt onto an enemy tank and threw a grenade inside it. He was killed, of course, but, through this painting, his name is immortalized.

Note the angle the artist chooses to depict the scene. We, the observers, crouch on the ground with Vojo Kushi above us. As befits his heroic status, Vojo is bare chested, with bare arms and feet. It packs quite a dramatic punch.

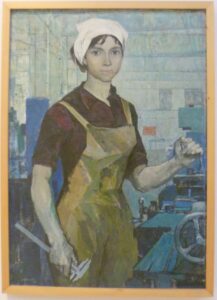

Zef Shoshi ‘The Turner’ (1969)

My final picture is of another female worker in a skilled occupation, this time as a turner in an engineering works. Note that her hair is tucked up out of the way, a safety precaution as well as a cosmetic one.

I doubt whether she earned as much as her male colleagues but after hundreds of years with no legal rights whatsoever (her very life was at the mercy of her male relations), having a paid job, and a vote, even if there was only one Party to vote for, must have felt like luxury indeed. At least for a while.

What is interesting about these Socialist Realist paintings is that most of them are, in fact, historical. They depict an Albania during the second World War and the post-war years at the height of its struggles. This can be no accident. Like it or not, by the late 1970s and without a rich Communist ally, Hoxha needed to face the fact that his ‘Brave New World’ may have turned into something akin to a nightmare – and his championing of this sort of art may be evidence of his ambivalence.

Do I like the art from this era? Actually, no. Having learnt of the horrors of the semi-starvation, the forced labour, Hoxha’s paranoid belief that evil Capitalists were just waiting to invade Albania, and how local communities were expected – as a show of loyalty – to pay for useless gun emplacements and hidden bunkers which they could ill afford, I find it difficult to view the paintings I’ve shown as anything other than a huge lie. They tell splendid stories, no doubt, but, emotionally, compared with Goya’s war paintings, for example, they are hollow.

Photos taken by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...