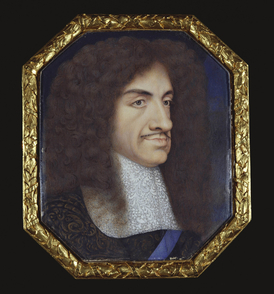

I’ve always had a soft spot for Charles II (1630-1680). I know he is often thought of as a lascivious, extravagant king, always short of money and having running battles with Parliament. I see him rather differently. Partly because, I confess, I find him a very attractive man; I know this shouldn’t affect a rational view of him 337 years on, but there we are.

- Charles II by John Michael at his coronation. He wears King Edward’s crown and holds the newly made orb and sceptre.

Charles may have had a gilded childhood but his life changed drastically when Civil War broke out in 1642. At thirteen, he was with his father at the battle of Edghill. For the next couple of years he fought with the Royalist army before fleeing into exile. He was in The Hague when he learnt of his father’s execution on January 30th, 1649. He was eighteen.

- Charger with picture of Charles hiding in the Boscobel oak. This is dated 1680, the year of Charles’s death commemorates the famous incident. The three crowns represent England, Scotland and Ireland.

In 1651 Charles invaded England at the head of a Scottish army – a venture which ended with Cromwell’s decisive victory at the battle of Worcester in September 1651. Charles fled the battlefield and, with a price of £1000 on his head, had a number of hair-raising escapes, including hiding in an oak tree whilst Cromwell’s soldiers prowled about underneath. He learnt to rely on ordinary people, like the yeoman, Richard Penderell, who, with his four brothers, was instrumental in getting him across England and safely on board ship to France.

- Nell Gwyn as Venus, mezzotint after Corregio’s ‘School of Love’.

Charles’s adolescence must have been traumatic. He fought in the Civil War at fourteen; he had to cope with the knowledge that his father had been publically beheaded; then, during the second Civil War, he was forced to accept the Scots’ stern Presbyterian Covenant before they would crown him; when he fled after the battle of Worcester he was under the constant threat of betrayal and the anxiety of finding a safe ship to take him to France. There was no royal protocol to cushion him; he had to rely on his wits and the support of strangers, few of whom he would ever have met in his old life. He must have learnt a lot – like getting on with ordinary people. Maybe this was part of Nell Gwyn’s attraction– she began her career selling oranges (and herself) in the theatre before becoming an actress.

- ‘Windsor Beauty’, Elizabeth Hamilton, Countess of Gramont as St Catherine, 1663 by Sir Peter Lely (1618 -1680)

The fascinating, newly-opened exhibition Charles II: Art and Power at The Queen’s Gallery looks at how Charles II set about renewing the monarchy, on his restoration to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 29th May 1660. The answer is, with a great deal of care and thought. Charles, in my view, was more politically savvy than his father. He might fill the Restoration court with pictures illustrating the glory of kingship, or portraits of court Beauties, but he was well aware that, compared with his first cousin, Louis XIV, the Sun King of France, the splendour he offered was largely an illusion. Parliament had the final say.

5. Miniature of Charles II, 1667. British School.

I’ve included the above miniature because…

The restoration of the monarchy was a time of general rejoicing – the diarist, Samuel Pepys, for example, records seeing people drink the King’s health in March, 1660, at first discreetly and then with increasing openness. People, generally, were fed up with the sobriety, the closure of the theatres, the banishing of Christmas as a time for feasting and jollity, the banning of maypoles and other traditional games. Cromwell’s Commonwealth was fairer but a lot more restrictive and a lot less fun.

6. The Garter Collar, part of the new royal regalia, as worn by James II at his coronation.

6. The Garter Collar, part of the new royal regalia, as worn by James II at his coronation.

Charles’s coronation, which Pepys attended, was spectacular and seems to have gone on all day and, from Pepys’s description, sounds enthusiastic but disorganized. The royal regalia had been melted down by Parliament during the Protectorate and had to be remade. Charles, who had spent much of his exile in France (Louis XIV was his first cousin) wanted to match the magnificence of Versailles, and the amount of silver-gilt, together with the silk and velvet costumes of the King, his family and the nobility, deliberately dazzled the eye.

It was so noisy that Pepys couldn’t hear the music and, eventually, had to slip out because ‘I had a great list to pisse.’ Plainly, in spite of almost universal rejoicing, the practicalities of hosting such a ceremony had been overlooked. Going home afterwards, Pepys noted the huge bonfires and he drank the King’s health so often that ‘my head began to turne and I to vomitt, and if ever I was foxed it was now… When I waked I found myself wet with my spewing. Thus did the day end with joy everywhere.’

7. Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, as Minerva, goddess of war and wisdom, c.1665 by Sir Peter Lely. She bore Charles II five children.

The claim of the monarch to have the Divine Right of Kings was not acceptable – Parliament had made that very clear – but Charles was still anxious to establish the legitimacy of the restored monarchy. His reinstatement of traditional royal ceremonies and ensuring that the court setting was as magnificent as possible with top quality furniture and works of art, and teeming with beautiful women (including several of his mistresses),all helped to emphasize royal power and prestige.

8. The Exeter salt by Johann Haas, a Hamburg goldsmith

8. The Exeter salt by Johann Haas, a Hamburg goldsmith

And Charles’s subjects played their part. For example, the city of Exeter, which had been staunchly Parliamentarian during the Civil War, presented him with the Exeter salt, a magnificent silver-gilt, and enamel fantasy castle, decorated with precious and semi-precious stones, with small drawers for holding spices, as an ‘gift of propitiation’, which Charles was graciously pleased to accept. Moreover, he let it be known that it would have a place of honour on his banqueting table; and other of his subjects with dodgy pasts, were encouraged to follow suit.

9. The Massacre of the Innocents by Pieter Brueghel the elder, 1565-7

With the downfall of the monarchy in 1649, the magnificent royal art collection was sold off. The most of the paintings which been bought by English buyers were returned, some donated willingly, others less so. Charles I had had an excellent eye for paintings and his son wanted the collection returned.

But many had been sold abroad, and retrieving them was more difficult. Charles bought a number of paintings from William Frizell, a dealer in Breda, including Pieter Brueghel’s Massacre of the Innocents. He was also given 28 paintings, including 24 Italian Old Masters as a present from the Dutch, in recognition of the connection between the Dutch and English royal courts; William II of Orange was Charles’s brother-in-law, and Charles had spent part of his exile with him.

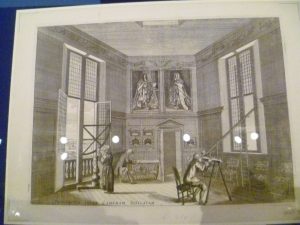

10. The Royal Observatory, 1676. An astronomer is studying the night sky

10. The Royal Observatory, 1676. An astronomer is studying the night sky

Charles had many faults as king but he had the gift of the common touch and ordinary people loved him. As one historian put it: ‘He was naughty but nice.’ At a more practical level, he founded the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, the first state-sponsored scientific establishment; he supported the Royal Society, which encouraged scientific experiment; he was Sir Christopher Wren’s personal patron; and he founded the Royal Chelsea Hospital for old soldiers, not to mention re-establishing the Royal Art Collection. Not a bad legacy.

I loved this exhibition. I loved the variety of objects, the different angles of interest in the galleries, and the intelligence with which it was curated. It runs at The Queen’s Gallery until 13 May, 2018.

Photos 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9 courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust/ © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017

Photos 2, 6, and 10 by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

I’m all for Charles II. What a ghastly dull world it must have been during the Protectorate! No rational enjoyment allowed. Hardly surprising everyone went overboard when Charles came back and gave everyone licence to live a normal life again. Aside from politics, of course, I’m sure the general populace must have been delighted when he returned to the throne.

You are right, Elizabeth, the general populace were delighted – Pepys’s diary is full of comments about the jollifications. It must have been wonderful when the theatres opened again – and with actresses, too, for the first time.

I really enjoyed this post, Elizabeth, and agree with Elizabeth! I’ve always thought Charles was an attractive man and must have had a charismatic personality. He’s one of our most interesting monarchs – wonder what he’d make of William’s and Harry’s lifestyles?

Thank you for joining the conversation, Jill. I suspect that Charles II would find Prince Harry the more sympathetic character; he’s managed to get into a number of scrapes and committed various indiscretions and survived which I think Charles would empathise with.