This is Mariana – and she has a problem. She was betrothed to Angelo, a man she was passionately in love with, but, when her dowry was lost in a shipwreck, the rat Angelo repudiated her. She now lives a lonely life in a moated grange. But things are about to change…

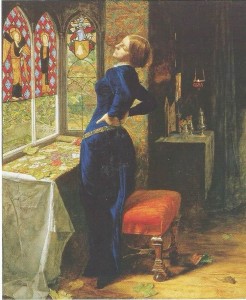

Millais’s painting ‘Mariana’

In 1851, the Pre-Raphaelite, J. E. Millais exhibited the Mariana above at the Royal Academy. The catalogue had a quote from Tennyson’s poem of the same name.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

‘She said, ‘I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead.’

Both painting and poem feature the same character, Mariana in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. But the two Marianas and moated granges are very different. According to Tennyson, the moated grange is a lonely building with ‘ancient thatch’, ‘gusty shadows’, ‘thick moted sunbeams’ and a mouse who, ‘behind the mouldering wainscot shrieked’. And we can see a good illustration of both in Millais’s later engraving for Tennyson’s poems in 1857 below.

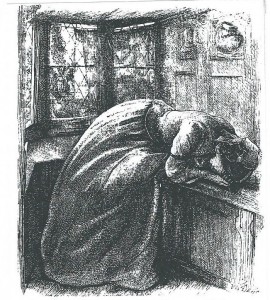

Millais’s engraving of Tennyson’s poem, ‘Mariana’,1857

It echoes Tennyson’s description of a dusty empty panelled room with cobwebs across the leaded windows. Mariana herself lies crumpled on the window seat, weeping. If a bubble came out of her head, it would say: ‘I would that I were dead.’

However, the ‘moated grange’ in the oil painting at the top of this post is plainly not Tennyson’s moated grange. There is no ‘mouldering wainscot’. By contrast, this is a bright, well-furnished room. The stained glass windows are clean and shining. True, there is a mouse, but it’s an ordinary mouse – hardly the doom-laden one of Tennyson’s poem. And this Mariana is not overwhelmed with grief. She looks bored and frustrated, but not suicidal.

An ordinary mouse

In my view, Millais’ painting refers to Shakespeare’s Mariana in Measure for Measure, not to Tennyson’s pathetic heroine, and the quotation from his poem Mariana in the R.A. catalogue is misleading. Tennyson had just been made Poet Laureate, so, possibly, Millais felt that the quotation would help sales.

We know that the Pre-Raphaelites worshipped Shakespeare and always celebrated his birthday. His Measure for Measure, though, was considered a ‘problem play’. The poet and theatre critic, Coleridge, said of it: ‘the comic and tragic parts equally border on the odious, the one disgusting, the other horrible.’ But, there was a rare opportunity to see the play in the actor-manager Samuel Phelps’ production at Sadler’s Wells in 1849 – he specialized in putting on well-crafted productions of Shakespeare in the original, unusual for the time.

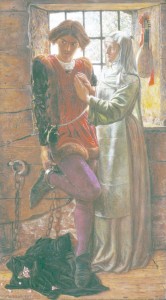

Holman Hunt’s companion painting from ‘Measure for Measure’: ‘Claudio and Isabella’

We know that Millais loved going to the theatre and was friends with James Wallack, an actor who’d acted with Phelps and greatly admired him. Furthermore, Millais and Holman Hunt, another member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, both subsequently painted characters from this obscure play and they often discussed their work in progress. The evidence is circumstantial but I cannot help thinking that they saw Phelps’ production.

In the play, Mariana does something shocking. To understand what and why, we need a brief summary of the plot.

The setting: Vienna. Duke Vincentio makes the saintly Angelo his deputy with instructions to enforce long-neglected laws against unchastity, and pretends to leave the city. Secretly, he stays in Vienna, disguised as a friar. Young Claudio falls foul of the new regime and Angelo sentences him to death for getting his fiancée pregnant. Claudio begs his sister Isabella, a postulant nun, to appeal to Angelo. Angelo falls for Isabella and promises that Claudio shall live if she will sleep with him. Isabella is outraged and refuses.

The Duke (the friar) tells Isabella to say ‘Yes’ to Angelo but, instead of going herself, Mariana, Angelo’s cruelly jilted betrothed, will take her place. Thus Isabella’s virginity will be saved and Mariana’s betrothal to Angelo will be consummated.

Mariana’s embroidery

The Mariana pictured at the top now begins to look much more proactive. No weeping in a dusty old room for her! She will shortly leave the moated grange for the first time in five years, go to Angelo’s ‘garden house’ in the middle of the night and sleep with him. It is a huge risk. I doubt that Tennyson’s Mariana would do it. But Shakespeare’s Mariana is made of sterner stuff.

Mariana’s pose

She is standing in what I think is arguably one of the most genuinely provocative poses in Victorian painting. Much of its power comes from the fact that she is unaware of the viewer. She has been working on her embroidery and has stood up to stretch; her hands, thumbs forward, are on the back of her waist, easing her spine. Her neck is up and her breasts are thrust forward. The resulting curves emphasises her femininity.

So, what were contemporary reactions to the painting? The Pre-Raphaelite William Michael Rossetti (brother of Gabriel) made a revealing comment in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Journal on May 2, 1851, shortly after the R.A.Exhibition opened: ‘Mariana’ appeared to be a great favourite with women, one of whom said it was the best thing in the exhibition. Why, one wonders. Perhaps women saw an aspect of themselves which was usually denied – their sexuality. This, after all, was the age where the eminent Dr William Acton pronounced: ‘As a general rule, a modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself.’

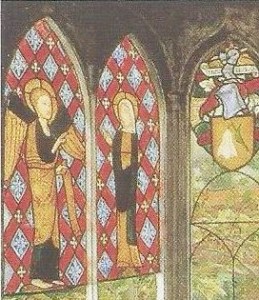

Millais’ ‘painted window’

It is interesting that the reviews fail to discuss Mariana’s seductive prose. The eminent art critic, John Ruskin, concentrated on what he saw as Millais’ ‘Romanist and Tractarian tendencies’. In a letter to The Times in May, 1851, he says: ‘I am glad to see that Mr Millais’ lady in blue is heartily tired of her painted window and idolatrous toilet table’. And, surely, it is not an ‘idolatrous toilet table’, it is Mariana’s small altar for her private devotions. And Ruskin, champion of all things Gothic, knew that perfectly well.

The ‘idolatrous toilet table’

Instead, he goes on about the draperies: ‘There is not a single study of drapery in the whole academy… which for perfect truth, power and finish could be compared for an instant with …the white draperies in Mr Millais’ Mariana.’

There is no mention of Mariana’s pose. In psychological terms, this is surely transference on a massive scale and we may well ask what Ruskin was avoiding in his determined concentration on the draperies. The answer was sex: Ruskin had married Effie Gray in 1848, but their marriage was still unconsummated when he wrote his letter to The Times in 1851. Mariana’s seductive curves may have been just too near the bone for comfort.

The broken snowdrop signifying consolation

The more one looks at the painting, the more interesting it becomes. If you Google Millais’ Mariana, you will find endless comments on the significance of the embroidery, the broken snowdrop on the shield, the stained glass depicting the Annunciation and even the mouse. But the Mariana they all seem to be discussing is Tennyson’s Mariana, not Shakespeare’s.

I’ve always loved this painting and I hope I’ve convinced you that’s it’s worthy of your attention. If you want to see it for yourself, it’s in Tate Britain.

Photos: Holman Hunt’s ‘Claudio and Isabella’ from the Chantry Bequest, courtesy of the Tate Collection; J. E. Millais’ ‘Mariana’, courtesy of the Tate Collection; other photos by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Thank you so much for this! We ‘did’ Mariana of the Moated Grange for O Level, and I remember thinking then Prem what a wimp she seemed. Sometimes when I’m feeling tired, I will recite, undr my breath and quite cheerfully, ‘I am aweary, aweary, I would that I were dead’

I had no idea it related to Measure for Measure (which I’ve never seen); Mariana now strikes me as feisty rather than feeble – far more the strong, decisive woman depicted in Millais’ painting, than the abject little weeping heap of the engraving.

Hurray! Thank you, Prem. It’s good to know that I’ve successfully made my point. But what a dreary poem to do for A Level; it’s very early Tennyson. You’d have been better off with one of the Idylls of the King, like The Passing of Arthur. He’s very good at conjuring up a feeling of drama and emotion, particularly in his later poems.

I just love your analyses, Elizabeth. What a terrific post. It reminds me that Measure for Measure, while I don’t much like it as a story, was responsible for my sudden enlightenment to Shakespeare. I’d enjoyed it for years – the poetry and the rhythms – even in my youth. But Angelo’s speech “Aye, but to die and go we know not where” hit me with an extraordinary force. All at once I “got” Shakespeare, realised how brilliantly he put things, how his innate understanding of the human condition was reflected in almost everything he wrote. I’ve loved Shakespeare ever since and worked with many of his plays as well as seeing them. It was one of my great pleasures, endeavouring to pass along that appreciation to my drama A Level students. Difficult, but ensuring they understood what they were reading was the first step.

I so agree – about Shakespeare, I mean. Claudio’s line about what happens to his soul: ‘to reside In thrilling region of thick ribb-ed ice’ always sends shivers up my spine. I taught ‘Measure for Measure’ in a crash adult A Level class and every year I saw something new in the play. I’m so thrilled you enjoyed the post.

I don’t see why Tennyson’s Mariana has to be categorised as a wimp. It is indeed a most depressing poem, but it is meant to be depressing. It is very much a description of depression.

Reading it again, I have thought that it could be seen as Mariana gradually building up to final state of rage at her situation. Weeping can often come with anger.

I do wonder about the shrieking mice, exactly why would a mouse shriek? A dust mite?

On a completely different note – the first line of the poem is used in “My Fair Lady’, when Higgins puts the marbles in Eliza’s mouth and requires her to read it.

Thank you for your most interesting comments, Michelle. Re: Mariana. what I was trying to get across was that I felt that Tennyson’s Mariana is more Victorian than Shakespeare’s. She’s doing what Victorian women of sensibility were expected to do – weep.

I absolutely agree with you about the shrieking mouse. A cat in the vicinity, possibly?

Thank you for the interesting Professor Higgins’ reference. I hadn’t noticed it before and I’m grateful to have it pointed out. If it comes from Shaw’s play Pygmalion, too, it’s even more interesting as he is known to have ‘despised Shakespeare’!