James Henry Leigh Hunt, to give Hunt his full name, was one of those people who everyone who was anyone in either politics or the arts knew, or at least knew of. In 1808, aged only 24, he, together with his older brother John, set up The Examiner, a weekly political paper which prided itself on its political independence; it was liberal and reformist in its opinions and it attacked, ferociously, whatever Hunt felt deserved it.

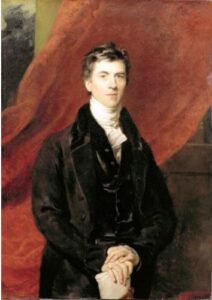

Leigh Hunt by Benjamin Haydon, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery

The Examiner’s circulation was tiny but it was popular and widely read – so much so that the Government kept an eye on what it said – and on the Hunt brothers. One of its early articles in 1811 was an attack on the brutal flogging then prevalent in the army and the government promptly prosecuted. The Lord Chancellor, Lord Brougham, a trained Scottish advocate, and a firm supporter of the anti-slavery movement, defended them brilliantly, and the brothers were acquitted.

They were less fortunate in 1812 when, at the annual political dinner of the progressives, they deliberately omitted the traditional toast to the Prince Regent; an omission which the staunchly Tory Morning Post criticized – publishing their own toast: You are the glory of the people – You are the Maescenas of the Age –Wherever you appear you conquer all hearts, wipe away tears, excite desire and love and win beauty towards you – You breathe eloquence, you inspire the Graces – you are an Adonis in loveliness . . .’

Leigh Hunt couldn’t resist. Ten days later The Examiner hit back: ‘This Adonis in loveliness was a corpulent gentleman of fifty! In short, that this delightful, blissful, wise, pleasurable, honourable, virtuous, true and immortal PRINCE was a violator of his work, a libertine over head and ears in debt and disgrace, a despiser of domestic ties, the companion of gamblers and demireps, a man who has just closed half a century without one single claim on the gratitude of his country or the respect of posterity.’

Lord Brougham by Sir Thomas Lawrence, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

As I typed all this, I realized that I was grinning from ear to ear! A man who could write this well, wasn’t afraid if being hard-hitting, and made his readers laugh was not going to have any trouble in selling whatever he chose to print.

This time, both brothers were heavily fined and given two year prison sentences – in different prisons. However, Surrey County Gaol, which took Leigh Hunt, wasn’t the harsh sentence it might have been. Hunt was given a pleasant room, which he had ‘papered with a trellis of roses, the ceiling painted with sky and clouds, the windows furnished with Venetian blinds, and an unfailing supply of flowers.’ His friends, who by now included, Lord Byron, Thomas Moore, Lord Brougham and Charles Lamb, paid for Hunt’s meals and comforts. When the writer, Jeremy Bentham, visited, he discovered Hunt playing battledore. And Hunt continued to edit The Examiner from prison.

John Keats, sketch by Benjamin Haydon, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

But Leigh Hunt had another circle of friends – a literary group who lived around Hampstead, which included Keats and Shelley, and his friendship with them helped both poets: Hunt wrote an article on ‘Young Poets’ and published it in The Examiner in 1816, and made their genius known to the public. Both recorded their gratitude, and Shelley helped Hunt financially.

Hunt had the gift of being able to write essays on a huge variety of subjects with a breadth of knowledge and a soundness of judgement; and he managed to do it with a light touch.

Let me give you an example, this time about women’s underwear!

Leigh Hunt wrote in 1830, ‘so rapid are the changes that take place in notions of what is decorous that not only has the word “smock” been displaced by the word “shift” but even that harmless expression has been set aside for the French word “chemise”, and at length not even this word, it seems, is to be mentioned nor the garment itself alluded to, by any decent writer.’ Leigh Hunt, no prude himself, obviously found the excessive primness ridiculous.

The tone is intimate – he writes as if he’s talking to a friend – probably, in this case, male – and he expects the reader to laugh with him at the absurdities he’s highlighting.

Hunt had many difficulties in his life, health and money troubles, principally, but, as one friend wrote: ‘his cheerful courage, imperturbable sweetness of temper, and unfailing love and power of forgiveness never deserted him.’

Jane Welsh Carlyle, 1856, by Mrs Paulet, courtesy of the National Trust, Carlyle’s House

He also had a gift for light verse which illuminated a precious moment: Here is one of his most famous, written after paying a visit to the historian Thomas Carlyle and his wife Jane.

Jenny kiss’d me when we met,

Jumping from the chair she sat in;

Time, you thief, who love to get

Sweets into your list, put that in!

Say I’m weary, say I’m sad,

Say that health and wealth have miss’d me,

Say I’m growing old, but add,

Jenny kiss’d me.

This, incidentally, is one of the poems I find myself saying whilst washing my hands – it takes 20 seconds to recite. ‘Jenny’, of course, is Jane Carlyle. It was Jane who wrote perceptively to Thomas Carlyle before their marriage, ‘I am not at all the sort of person you and I took me for.’ It wasn’t an easy marriage; there were money troubles; and Jane suffered from ill health and groundless jealousy, but she was valued as a friend by many, including Leigh Hunt.

Percy Bysshe Shelley by Amelia Curran, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Hunt enjoyed setting up sonnet competitions between his poet friends: a subject would be chosen and the competing poets would submit their poems to The Examiner. The 1818 competition was on ‘Ozymandias’ the colossal statue which was (if it survived the journey) coming to the British Museum. Shelley’s poem of that name won. (And you can read all about it in my blog: Shelley, ‘Ozymandias’ and Ramesses II : category: poets.)

Times change and The Examiner’s sales dropped off. Hunt began to look elsewhere, living abroad was cheaper and, maybe new opportunities would arise there.

In 1817, at the invitation of Lord Byron and Shelley, Hunt and his family joined the two poets in Italy; Byron and Shelley were looking to establish a quarterly liberal magazine. The Hunt family arrived in July 1821 and moved, with Shelley to Pisa. In 1822 Lord Byron wrote to his friend, the poet Thomas Moore: ‘Leigh Hunt is sweating articles for his new journal; and both he and I think it somewhat shabby in you not to contribute. . . I recommend you to think twice before you respond in the negative.’ But the venture was not a success. Byron procrastinated and Hunt found himself in the embarrassing position of being forced to ask him for financial assistance.

On July 8th, 1822, Shelley was accidentally drowned in a storm and Hunt, Byron, and the author and adventurer Edward Trelawny, were present at Shelley’s funeral cremation on the beach.

Shelley’s cremation by Louis Edouard Fournier, 1889, courtesy of Walker Art Gallery

It was Hunt who chose the epitaph for Shelley’s gravestone in the Protestant cemetery in Rome; three lines from Shakespeare’s Tempest.

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange

The relationship between Hunt and Byron faded rapidly. Byron wrote to his publisher, John Murray in November: ‘as to any community of feeling, thought or opinion, between L.H. and me, there is little or none: we meet rarely, hardly ever; but I think him a good, principled and able man . . . . For a while the Hunts lived with the widowed Mary Shelley, then Hunt and his family returned to England in 1825.

Shelley’s tomb in the Protestant cemetery, Rome

Hunt wrote unremittingly, and tried one thing after another but it was becoming an uphill struggle and his health was cause for concern, too. His friends managed to get him various grants and annuities, which helped. This list of his published works is a long one and it includes innumerable essays, a number of fine poems,and a successful play, A Legend of Florence, which Queen Victoria saw several times.

One of his happiest poems is A Song of Fairies Robbing an Orchard, which has a typical Hunt lightness of touch. It’s in three verses, of which I’m giving you the second two:

Stolen sweets are always sweeter,

Stolen kisses much completer,

Stolen looks are nice in chapels,

Stolen, stolen, be your apples.

When to bed the world are bobbing,

Then’s the time for orchard-robbing;

Yet the fruit were scarce worth peeling,

Were it not for stealing, stealing.

I can’t think of another poet who could pull this off. The tone is mischievous and light. The fairies are the kindred of Shakespeare’s Puck, Moth, Mustardseed, Cobweb and Peaseblossom – they might be a nuisance, but they don’t inspire fear.

I’m ending with Hunt’s poem, Abou Ben Adhem, published in 1834; it is one of his most successful and it has often been anthologized.

Abou Ben Adhem (may his tribe increase!)

Awoke one night from a deep dream of peace,

And saw, within the moonlight in his room,

Making it rich, and like a lily in bloom,

An angel writing in a book of gold:—

Exceeding peace had made Ben Adhem bold,

And to the presence in the room he said,

‘What writest thou?’—The vision raised its head,

And with a look made of all sweet accord,

Answered, ‘The names of those who love the Lord.’

‘And is mine one?’ said Abou. ‘Nay, not so,’

Replied the angel. Abou spoke more low,

But cheerly still; and said, ‘I pray thee, then,

Write me as one that loves his fellow men.’

The angel wrote, and vanished. The next night

It came again with a great wakening light,

And showed the names whom love of God had blest,

And lo! Ben Adhem’s name led all the rest.

Leigh Hunt died on 28th August, 1859, and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. Ten years later, his bust by the sculptor Joseph Durham was placed on his grave; engraved underneath was a line from the above poem: Write me as one that loves his fellow men.

It is a fitting epitaph.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Very interesting . What a brave, talented man.

Thank you, Jan. I’m surprised that he’s not better known, save for a few short poems. I enjoy the way he writes.

I love this. Thank you.

Thank you, Lesley. His son said of him, ‘Few men were more attractive in society, whether in a large company or over the fireside. His manner was particularly animated, his conversation varied, ranging over a great field of subjects.’ He’d have been brilliant on TV, hosting a chat show!

Great to learn more about him. I only knew him from his poetry. Had heard of The Examiner, but had not taken in that he was its creator. A poignant history.-

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. There seems to have been a lot of interesting and talented 19th century men whose lives were made infinitely more difficult by a shortage of money and a superfluity of children! Leigh Hunt was one, and Benjamin Haydon another. When Hunt accepted Byron and Shelley’s invitation to join them in Italy, he went – and so did his wife and seven children. I couldn’t help thinking how many writers’ (and their wives’) lives would have been immeasurably improved by contraception! Dickens’, for one – not to mention his poor wife.

I am not usually the sort of person that reads poetry, but that last poem (Abou Ben Adhem) is lovely.

Thank you for sharing it.

I’m delighted that you enjoyed it, Huon. I’m also pleased that you are now a person who occasionally reads poetry – and enjoys it. A good poem gives one pleasure for life!

I enjoyed this a lot. I knew very little about Leigh Hunt except fir his friendship with Shelley so it was very enlightening.

Thank you for your comment, Pauline, especially as it’s not often I manage to tell you something that you don’t already know! Leigh Hunt was one of those behind the scenes figures who, through The Examiner, had a huge influence on the way intelligent people thought.