I’ve always loved Victorian magic shows with their sleights of hand and appearances that trick the eye. To my delight, this year’s exhibition, Queen Victoria’s Palace, at the Summer Opening of the Buckingham Palace State Rooms, offers a genuinely Victorian touch of magic with an optical illusion known as Pepper’s Ghost. I couldn’t wait.

But first, a bit of background…

It’s 1837 and the 18-year-old Queen Victoria has just ascended the throne. She is not going to stay in stuffy old Kensington Palace while Parliament dithers about the cost of renovating Buckingham Palace, which has been empty since the death of George IV seven years before. Six weeks into her reign, and against her ministers’ advice, she insists on moving in. (One suspects that wants to get away from her over-controlling mother, the Duchess of Kent, and start her new life as soon as possible.) Parliament continues to dither.

In 1840, Victoria marries her first cousin, the handsome Prince Albert. By 1845, they already have four children and it’s clear that they are outgrowing their accommodation. The Queen decides that the dithering must stop and writes a terse letter to her Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel concerning, ‘the urgent necessity of doing something to Buckingham Palace’ and ‘the total want of accommodation for our growing little family’.

There are other reasons, too. She needs a palace with suitable rooms for all the functions she has to host as Queen: the concerts, balls, investitures, etc. As it stands, the rooms in the palace are too small. Furthermore, the general offices and servants’ rooms are basic, to say the least.

In 1847, the architect Edward Blore was commissioned by Parliament to extend and modernize Buckingham Palace. The Palace was U-shaped, so Blore added an east wing along the front (which included the famous balcony) facing the Mall, giving the Palace a central courtyard. On the first floor of the west side he created a number of State Rooms with various smaller rooms like the Ante Room, the Silk Tapestry Room, and the Guard Room. All the rooms are corridor rooms, that is, you can walk through from one to the next. Many of them are designed to be multi-purpose. The Palace has hosted banquets in the Picture Gallery, the Ballroom and the State Dining Room, for example, and the exhibitions accompanying the annual Summer Opening of the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace take over a couple of the rooms and the curators adapt them as necessary and move furniture and paintings about.

The red and gold supertunica, the ceremonial robe made for Queen Victoria’s coronation

This year, the Ball Supper Room sets the scene for the Queen Victoria’s Palace exhibition, displaying items from Victoria’s youth, for example, her specially made red and gold supertunica, the ceremonial coronation robe.

Queen Victoria’s dress for the Stuart themed ball in 1851

Victoria and Albert held three magnificent themed balls in their newly upgraded home, which included a magnificent Ballroom by the architect, James Pennethorne, and the Queen encouraged her guests to commission elaborate costumes from the silk weavers in Spitalfields whose business was in sharp decline, thanks to machine-made lace being so much cheaper.

Victoria own sumptuous dress for the Stuart Ball in 1851, harking back to King Charles II’s Restoration court, was designed by the artist Eugene Lami, and its bodice and full skirt are grey moiré trimmed with gold lace with an underskirt of gold and silver brocade

The watercolour above by Louis Hague is the only record we have of how the ballroom originally looked. The décor is inspired by the Italian Renaissance and devised by Prince Albert’s artistic mentor, Ludwig Gruner.

Nowadays, its walls and ceiling are white and gold. This year it’s been transformed into the ballroom for the Crimean Ball of 1856, which was held in this very room, and given to mark the end of the Crimean War and to honour the returning soldiers.

Digital projections have magically taken the visitor back in time and transformed the Edwardian white and gold décor into Louis Haghe’s 1850s Italian Renaissance Ballroom

The historian and biographer, Dr Amanda Foreman, and the Assistant Curator of Paintings, Lucy Peter, have together curated the Queen Victoria’s Palace exhibition and they have come up with some unusual solutions in order to give the visitor a feel for how it might have looked on 17th June, 1856. First, they digitally projected the original Louis Haghe designs onto the walls and ceiling.

Four ghostly couples dance

Second, and this is where the Pepper’s Ghost illusion comes in, the first thing the visitor sees are four life-size couples dancing the opening waltz in Verdi’s La Traviata, the very piece of music which opened the Crimean Ball back in 1856. There is no film projector, the couples are just there. Behind and above you, thanks to the digital projections, the walls, ceiling and gas-lit chandeliers glow with the jewel-like colours the guests would have seen.

The effect is magical and slightly eerie.

As you leave the room to go into the narrow West Gallery which leads to the State Dining Room, there is a board explaining how Pepper’s Ghost works – it’s a question of a glass, a mirror, a black curtain and a very carefully calculated angle.

Royal Collection Trust / (c) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019.

The State Dining Room has been set up for the Crimean Ball State Banquet. My first thought was how pretty it looked.

Back in 2015, the banqueting tables were more formally laid for the Summer Opening Exhibition ‘A Royal Banquet’.

The other State Banquet I’d seen set up was for the 2015 Summer Opening exhibition A Royal Banquet, when the curators replicated the banquet for a recent Japanese State Visit. That was, of course, impeccably designed with immense care to give pleasure to their Japanese guests, and it glittered with gold and beautiful Japanese flowers on snowy-white damask tablecloths. Magnificent? Undoubtedly. But pretty?

I decided that dining at a Ball allows a certain degree of informality which would be out of place for a State Visit. Buckingham Palace, of course, has understood this perfectly.

One corner of the banqueting table.

The Crimean Ball banquet’s attractiveness was enhanced by the turquoise, gold and white of the ‘Victoria’ pattern Minton dinner service, which had been bought by the Queen from the Minton stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and which was perfectly set off by the polished mahogany of the table top.

The Alhambra centrepiece

The Alhambra Table Fountain, a silver-gilt and enamel centrepiece, was commissioned by Victoria and Albert from Garrard in the same year. It’s way over the top, but, on the other hand, there’s only one of it and its presence surely ensured that the conversation never flagged.

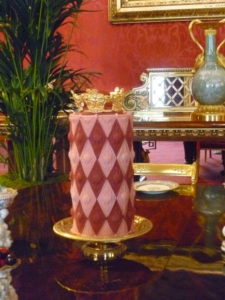

The pink tower dessert designed by Charles Elme Francatelli

There are also two examples of desserts on the table, based on designs by Charles Elme Francatelli, Queen Victoria’s Chief Cook. The pink tower above has sponge cake inside and its outside is coated with marzipan lozenges in pink and red. The crown at the top is gilded. It rests on a silver gilt base.

Charles Elme Francatelli’s tower of crystallized fruit

The other dessert is a tower of crystalized fruit: the frosted sugar which coats the fruit twinkles. The whole concoction looks delicious.

I love the other small Minton items of tableware, too, like the cherub standing between two seashells which hold cherries. Just looking at it gave me a lot of pleasure.

Minton cherub with cherries

Dr Amanda Foreman was in the State Dining Room ready to answer any questions. She had some interesting thoughts on how Victoria tackled being Queen. Britain hadn’t had a queen since Queen Anne died in 1714, and the young Queen had no guidelines as to what her role should be. For well over a hundred years the default position was that of a male ruler; men who were interested predominantly in war, power and status among their peers ruling various kingdoms in Europe. King George II had actually fought, and distinguished himself, at the battle of Oudenarde in 1706; King William IV was a sailor, and he’d worked his way up the ranks and fought in various naval engagements. There was no way that Victoria, a women, could ever offer anything similar.

And she didn’t. Instead she presented herself as a queen who upheld womanly virtues as the important ones, like – well, virtue, for a start. Victoria prided herself on her role as wife and mother. There were no unseemly liaisons going on in her court. Her beloved Albert was a faithful husband and a father who cared about his children – unlike the Hanoverian Kings whose family relationships were notoriously disastrous.

She was also patriotic. She cared deeply about the welfare of the soldiers in the Crimean War and was the first monarch to invite wounded soldiers to Buckingham Palace. Note the Royal Family standing on the new balcony to acknowledge the troops’ cheers in William Simpson’s picture above.

Victoria also instituted the Victoria Cross ‘for valour’; it was open to men of all rank – not just officers – and both services. (The exhibition displays the prototype for the Victoria Cross.) And it was Victoria who first held Garden Parties at Buckingham Palace with a much wider guest list, socially speaking; these were people who she felt deserved to be invited. For Victoria, this much less to do with rank, and more to do with what the invited guests had contributed towards helping their fellow men.

Her chosen path was so successful that she succeeded in changing the narrative, as Dr Foreman put it. Nowadays, the Royal Family are expected to do what they can to help those less fortunate, to set up charities, to hold garden parties for good work done by their humbler subjects, and so on.

It is Queen Victoria we have to thank for that.

All photos by Elizabeth Hawksley, unless otherwise stated.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...