The sumptuous new exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery, Japan: Courts and Culture which opened on 8th April, 2022 and runs until 12th March, 2023, displays some of the finest works of Japanese art in the western world, and covers items dating back to 1613, when King James I was presented with a magnificent suit of Samurai armour as well as other gifts by the Shogun Tokugawa in the Japanese Emperor’s name. This is the earliest Japanese item in the Royal Collection.

More importantly for the British, the British East India Company was officially permitted to trade with Japan and the 350-year relationship between the Japanese Imperial and the British royal houses began. Sadly, the initial entente cordiale lasted only until the 1630s when Japan closed her borders to the outside world in an attempt to control foreign influence – a state of affairs which lasted for 220 years.

2. These attractive pieces of blue and white porcelain probably came from the collection of Augustus II of Saxony who set up his own porcelain factory once he knew the secret of how it was made

However, once the Stuarts had seen the wonderful Japanese porcelain and lacquer work, neither of which were known in Europe, they set about acquiring examples from European merchants wherever they could. Somehow, between 1639 and 1854, British royalty managed to keep in contact with the Japanese Imperial family, if not in person, then at least through their purchases. And, if Japanese merchants weren’t willing to sell porcelain, this couldn’t be said of the Chinese who swiftly produced a variety of blue and white porcelain aimed specifically at the European market.

3. Two sake bottles 1840-1860. Probably sent to Queen Victoria by Shogun Togugawa Iemochi, 1860

In the early years, the West had difficulty in knowing the difference geographically between India and Japan, and China and Japan. Did that matter so long as they got the luxury goods they coveted? But the trade secrets of porcelain eventually came out and top quality porcelain factories spread throughout Europe.

By the mid-19th century, the Japanese Imperial and British royal families were officially back in touch, and various British princes were sent off to Japan to broaden their minds and forge good relationships with the Japanese Imperial family.

Personally, I love blue and white porcelain, but, the new royal British owners of porcelain items obviously felt that they needed mounts. The moment I saw a vase with mounts, I was instantly taken back to the George IV: Art & Spectacle exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery in 2019 when I first learnt what ‘mounts’ were. As one of the guides explained: ‘it was fashionable during the Regency to add extra bits to art objects to make them even more arty.’ She pointed to two Chinese vases under two small tables. ‘Originally, they would have been plain,’ she said. ‘The Chinese themselves did not go in for over-ornamentation.’

The guide continued: ‘What the Prince Regent wanted was to make the art object even more Chinese than it was already.’ I was staggered. I’d always believed that the gold rims at the top of a vase, or the gold stands at the base were part of the original. This, surely, was what Chinese/Japanese vases were really like.

Apparently not.

4. One of a pair of vases with covers. These vases are Chelsea porcelain dating from 1750-75 which have been given gilt bronze mounts. They were probably bought by George IV who definitely went in for mounts.

In other words, mounts were decorative bits of ornamentation, usually in gilt, gold, or silver-gilt, which transformed the original object into something else entirely.

5. The mounted jar above proves my point. The original porcelain jar has been mounted with gold and gilt bronze for use either as an urn or for pot pourri

George IV bought it in Paris, already mounted, and it ended up in the Brighton Pavilion.

We can see that, by the 18th century, the distinction between Chinese and Japanese porcelain was becoming blurred – let alone the question of the mounts; but we need to remember that, in the 18th century, the Imperial Japanese and the British royal families were no longer directly in touch.

6. I love these porcelain hares – or rabbits? Here, they are a pair of pastille burners.

The hares look as if they are wearing patchwork, perhaps against a chilly night. When they were in the Brighton Pavilion, their garments were described in the inventory as ‘harlequin patches’ Although they come from the Japanese province of Hizen, the hares themselves have been ‘borrowed’ from China, perhaps in recognition of The Year of the Rabbit, the 4th year in the Chinese calendar. But hares have longer ears than rabbits and they don’t have white powder puff tails like rabbits.

An exquisite lacquer box which contains drawers to hold precious objects.

I found myself wondering what the Imperial Japanese visitors thought of what had been done to their porcelain gifts when they visited the United Kingdom and saw them displayed with the added golden glitter of the mounts? Did they think them vulgar, perhaps? Or even ugly?

In 17th century Europe, the secret of the use of lacquer, together with the recipe for porcelain, were unknown. Lacquer comes from the sap of the Toxicodendron verniciflua tree and it has been used in Japan since 4000-3000 BC as a durable finish for luxury wooden objects or temple furniture. It is resistant to water, heat, woodworm, and it can be coloured or sprinkled with metallic powder. It takes a very long time to prepare and execute; each layer must be allowed to dry thoroughly and rubbed smooth before the next layer is added. It is an onerous task and needs an immense amount of skill.

Porcelain is based on crushed granite mixed with china clay which was extremely difficult to work.

8. Cosmetic box decorated with a heron, given to Queen Elizabeth II to commemorate her Coronation in 1953. It is made of wood with black, gold and silver lacquer

This has to be one of the most precious objects in the exhibition. It’s creator, the Imperial Household Artist, Shirayama Shosai (1853-1923), has incorporated miniscule streaks of gold to set off the softness of the silver feathers.

9. Lacquered cabinet with shelves

On the whole, the Japanese do not go in for furniture; shelves, like the one above, were reserved for the very richest families. One shelf might hold cosmetics, another might be for writing implements and books, and the third for incense equipment and small boxes. Queen Victoria was given the above item by the Shogun Tokugawa in 1860 and I was rather amused to note that the British Consul General itemized it somewhat helplessly as ‘1 dioesu (a sort of cabinet)’.

Once the two royal and Imperial families had re-established contact in the 1850s, the exchange of gifts continued more freely; British princes visited Japan and diplomatic and political links were secured. The early 20th century saw reciprocal Imperial and royal attendances at Coronations and the like; they were on each others’ Guest Lists.

10. A group photograph of Edward, Prince of Wales’s visit to Japan. Fortunately, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) and the Japanese Prince Regent were able to converse in French. 1922.

11. I’d now like to look at this late 19th, early 20th century screen which dates from this time and which I think is wonderful.

11. Silk screen: one of the stars of the exhibition

It comprises four panels, each representing a season: the left hand one features cranes and ducks, which represent winter, for example. What astounded me was that, at first I thought it was painted, but it isn’t. It’s exquisitely embroidered; the glossy feathers of the cranes are stitched with flat silk; long and short stitches help to blend the colours and create movement; round knots at the end of flower stamens emphasize the reality of the flowers. Looked at closely, the flowers, trees and birds almost come alive.

12. Inkstand in the form of a pheasant

Another object which really caught my attention was this silver, gold, enamel and ivory inkstand in the form of a pheasant, dating from 1868-1912. A pheasant’s plumage is iridescent and the enamelling brings this out beautifully. According to the label, it was probably acquired by King Edward VII – that enthusiastic shooter of game – it fits. Apparently, an inkwell is cleverly concealed somewhere – possibly under the wing but I couldn’t see it myself.

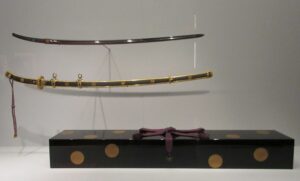

And I cannot omit to mention the splendid array of swords and armour, so important to the Japanese. I like the stories which accompany the chosen objects, and this sword was particularly appealing for the venerable age of its creator.

13. Field Marshal’s sword, scabbard and storage box made of gold, silver and leather (1918)

The note tells us that the blade is signed and inscribed: Gassan Sadakasu, Imperial Household Artisan, respectfully made this at age 83. It was presented to King George V by Prince Higashi-Yorihito on behalf of the Emperor Taisho, 29 October, 1918.

It is beautifully made and I’m delighted that I was able to photograph it successfully myself.

Finale:

Artistic exchange: Coloured woodcut: Buckingham Palace London, seen across Green Park (c. 1911) by Yoshio Markino (1869-1956)

The influence that Japanese and Chinese art had on artists in the west, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards in well-known, what is less well-known is what Japanese artists took from Western art. First, perhaps, was the art of painting perspective but there is more. Here, in this exhibition, we see how Yoshio Markino reacted to London’s mists and fog – seeing Buckingham Palace through a London fog as ‘ghostly allure’ rather than using a ‘pea-souper’ soubriquet most coughing and wheezing Londoners might prefer. In reality, London’s smoke and fog clogged up the lungs. Where Markino sees the beauty of the rosy glow of the gaslights in front of Buckingham Palace; a Londoner would smell the gas from the gas lamps and note how dirty his clothes got.

Japan, Courts and Culture is a once in a lifetime exhibition, and well worth seeing. Get your ticket stamped as you go out and get in free until March 12th , 2023.

© Elizabeth Hawksley

Acknowledgements:

Photographs 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11 and 14

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Photographs 2, 4, 5, 9, 12 and 13 © Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...