Margaret Llewelyn Davies (1861-1944) was, from the 1890s to the 1930s, an inspirational campaigner for women’s causes who has, quite undeservedly, been allowed to slip almost into oblivion. Fortunately, a new book, Margaret Llewelyn Davies: with Women for a New World by Ruth Cohen, has just been published which sets the record straight. So what did Margaret do that we should remember her?

Margaret as a young woman: attractive, energetic, persuasive and with a great deal of charm; her friend Virginia Woolf remarked that she could ‘compel a steamroller to dance.’

Margaret was born into an educated upper-middle class family with many links to the intelligentsia of her day. Her aunt, Emily Davies, for example, was a passionate believer in education for women and founded Girton College, Cambridge. Her parents knew J.S. Mill, Carlyle, Ruskin, and the pioneering doctor Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. It was seen as not only normal, but expected, that the Llewelyn Davis children (six sons and one daughter) should play their part in doing something worthwhile with their lives.

In 1889, Margaret became the general secretary of the Women’s Co-operative Guild (WCG), a post she held for 32 years and through this respectable organization began an astonishing programme for radical change in the lives of working-class women.

What I particularly admire about Margaret is that she wasn’t an interfering middle-class ‘Lady Bountiful’; far from it, she actively encouraged the Guild’s working-class women members to become visible, to speak in public, an innovation which entailed standing up to the men in the Co-operative movement for whom, generally speaking, issues affecting women were of minor concern. Indeed, some of them were actively hostile, not only to their wives speaking in public but even about them attending their local Co-operative Guild meetings. As one man put it; his wife should ‘stay at home and wash my moleskin trousers.’

Encouraged by Margaret, the women of the WCG became formidable fighters in fields such as equal pay; divorce reform; women and children’s health; and women’s suffrage. Women members were encouraged to write reports and read them out loud to others in their local branch; to take an active part in discussions; and finally, to talk in public – seen as a shocking innovation by some: respectable women were meant to lead private lives.

Take the redoubtable Mrs Bury from Darwen in Lancashire, a woman who started half-time mill work aged seven, and educated herself at night school, whose story shows how far an intelligent working-class woman could go, given half a chance. In the late 1890s having helped to set up her local branch, Mrs Bury found herself at the Annual Meeting:

‘… here was the very opportunity I had always been seeking, but never put into words … At the close of the meeting I felt as I imagine a war horse must feel when he hears the beat of the drum…’

Working class women realized that they didn’t need an educated lady to speak for them, or a male member of the Co-operative Society who might not see female concerns (like equal pay) as of major importance; women themselves could write reports and speak and become, as one women put it, ‘As brave as a lion.’. WCG women came to see that, if they were united and held firm, eventually, (though it could take years) they could change things.

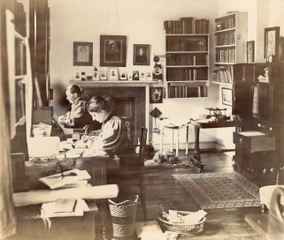

Margaret’s office in the vicarage at Kirby Lonsdale where her father look a living in 1889. She had to uproot herself from her work in London and start again, but it brought her closer to the industrial north-west, the centre of the co-operative movement

One of the Women’s Co-operative Guild’s most harrowing and hard won struggles was to get Parliament to pay maternity benefit to mothers, rather than to fathers who, Margaret felt, might not pass it on. Moving on to look at the need for other kinds of help with maternity, Margaret decided to ask 600 or so current or past WCG officers, mostly mothers themselves, to write to her privately and tell their stories. The 386 replies revealed just how shocking poverty and the resulting suffering could be. The writers did not pull their punches:

‘For fifteen years I was in a very poor state of health owing to continual pregnancy. As soon as I was over one trouble, it was all started over again. In one instance, I was unable to go further than the top of the street the whole time, owing to bladder trouble, constant flow of water… I have had four children and ten miscarriages.’

Medical treatment was inadequate or just not available, and, in any case, many women could not afford a midwife. There was no access to contraception – which was frowned upon anyway. And belief in a husband’s ‘conjugal rights’ was strong: … ‘within a few days of the birth … she is tortured again. If a women does not feel well, she must not say so; as a man has such a lot of ways of punishing a woman if she does not give in to him.’

In 1915, Margaret compiled and published a selection of the letters in Maternity: Letters from Working Women. It is a deeply moving book and it had a considerable impact on public opinion (it was republished by Virago in 1978). Eventually, Parliament passed the 1918 Maternity and Child Welfare Act but, amid all the privations of the First World War, little was actually done. But it was, at least, on the Government’s agenda, and it can be argued that Margaret and the Guild’s campaign influenced future national and local policy in this area.

Medallion presented to Margaret by the Women’s Co-operative Guild in 1922, after her retirement, in appreciation of her work there. It depicts an angel dressed in blue (her favourite colour) holding a marguerite, which has visibly strong roots. The legend reads: OF WHOLE HEART COMETH HOPE

Between 1904-1914, the Women’s Co-operative Guild was deeply involved in the struggle to get women the vote. The third Reform Act in 1884 had enfranchised all men – but only if they fulfilled a property qualification which, in practice, only 60% of them did. When, in 1904, Parliament was preparing to consider allowing all men the vote, and dropping the property qualification, Margaret was determined that women’s right to vote should also be on the agenda.

The next ten years were tumultuous ones for the votes for women campaign as they argued which were the best tactics to adopt. Should they agree to throw all their energies behind getting the men the vote first and hope that they could follow, holding onto the men’s coattails, as it were. Should they support the Suffragettes violent tactics? These were hotly argued questions – and it became obvious that, in spite of some supportive-sounding words, many politicians were, at best, lukewarm, and, at worst, determined that women should not get the vote.

But the campaigning came to a full stop when the First World War broke out. One thing the war did, however, was to prove beyond a shadow of doubt that women were quite as capable as men of doing all sorts of jobs on the home front which had previously been seen as exclusively male.

The different campaigns the WCG instigated often overlapped, and the higher wages for women campaign was fought mainly between 1906-1913. There was the question of a minimum wage – women actually working for the Co-operative shops were often paid a pittance – not only much less than the men, but, shockingly, often less than in other occupations. Surely, the Co-operative Movement, of all people, should pay the women it employed a decent wage in keeping with their founding principles?

And why were the women paid so much less than the men, anyway? They worked just as hard and kept the same hours. Some women began to argue for equal pay!

But the campaign which caused the most uproar and division, both within the WCG and in the Co-operative Movement as a whole between 1906-1914, was the campaign to change the divorce laws. This was not just a WCG initiative, Sir John Gorell Barnes, the most senior divorce court judge, had publically stated that the current law was riddled with, ‘inconsistencies, anomalies and inequalities almost amounting to absurdities.’ In 1909, a Royal Commission was set up to look at the whole question of divorce.

From a working-class woman’s point of view, the current divorce laws were a disaster. A man could get a divorce on grounds of adultery alone; a woman had to prove adultery and another offence, such as cruelty, desertion, persistent drunkenness or incurable insanity. And this was not taking into account the cost of divorce which was out of the reach of most ordinary people.

Again, the evidence was hard-hitting. ‘I know of women who always try to bring on an abortion when first they are pregnant … because the husband will grumble and make things unpleasant because there will be another mouth to fill and he may have to deprive himself of something. In one case the man always thrashes his wife and puts her life in danger in his anger on discovering her condition.’

This was a long drawn-out campaign which Margaret and her allies did not win. It was 1969 before the divorce laws finally became fairer and actually workable.

J. M. Barrie by George Charles Beresford, 1902. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Margaret’s personal life, away from the Women’s Co-operative Guild, also had its own ups and downs; and the book examines the two family tragedies which affected Margaret deeply. In 1905, her brilliant thirty-four-year old brother Theodore drowned accidentally in a local pond. It came out of the blue and Margaret was devastated. Then, only two years later, another much-loved brother, Arthur, died of cancer, followed a couple of years after by his wife Sylvia, daughter of the novelist and cartoonist, George du Maurier, leaving five orphaned boys between two and fifteen years old. Margaret did what she could to help but she was in a difficult position.

After her mother’s death, Margaret, as the only daughter of the family, had stepped in to look after her father, now in his eighties – as was considered only proper at the time. And she was continuing to run the WCG which entailed a huge amount of work as she prepared the Guild’s new campaign on Women’s Suffrage.

Margaret was not a natural with children but she did her best. The rich and famous playwright J. M. Barrie was a close friend of Arthur and Sylvia and he helped with the medical costs. He obviously loved both Sylvia and the boys – and ‘Uncle Jim’ became part of their family. After Sylvia’s death, the question arose of who should look after the five boys. Sylvia had been adamant that they should not be separated. Margaret was nearly sixty, and not only did she have her aged father to look after, she had the Guild to run. Her younger brother Maurice, a widower, had three children of his own; he offered to take two of the boys but he couldn’t manage all five. In the end, it was Barrie who took over and brought them up.

The five Llewelyn Davies boys became known to posterity as ‘The Lost Boys’ (after the Lost Boys in Barrie’s famous play, Peter Pan.) Barrie’s involvement was, from a modern point of view, questionable. Barrie’s own childhood was tragic and dysfunctional and he seems to have felt the need to have emotional control over those he most loved; as the writer D. H. Lawrence put it: Barrie has a fatal touch for those he loves. They die. Three of the boys died tragically – two of them committing suicide. Margaret kept in touch with them as they grew up and did her best, visiting them at school, and so on, but she was, inevitably, on the edge of their troubled lives.

I found it impossible to read this episode without tears.

One of the most impressive things about this book is that Ruth Cohen manages to keep her readers both emotionally involved and up to date with the different threads of the various WCG campaigns, without tangling the reins. I found her telling of Margaret Llewelyn Davies’s life both inspiring and a great read.

Margaret Llewelyn Davies: With Women for a New World by Ruth Cohen is published by Merlin Press at £17.99. ISBN 978 0 85036 759 1

All photographs courtesy of Jane Wynne Willson, unless otherwise stated.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Highland Summer is now out in ebooks

www.amazon.co.uk/Highland-Summer-Elizabeth-Hawksley-ebook/dp/B08DCBKV7N/

Please share this page...

This is fascinating. I had never heard of her, and the connection with the “lost boys” is a wonderful find.

I know just what you mean, Elizabeth. I knew about the ‘Lost Boys’ tragic story years before I came across Margaret Llewelyn Davies’s life and work. It was quite a shock to realize that she was the boys’ aunt. She and Sylvia, the boys’ mother, did not get on well; Sylvia found Margaret too intense and emotional; and Margaret thought Sylvia too frivolous. Sylvia was a very private person under her feather-brained exterior, which made things difficult.

I have a birthday coming up and this is going on the list, thank you. I wrote a play about Barrie for Theatre Broad, JMB and M’Connachie, so I did a huge amount of reading about JMB and his life. I didn’t know about Margaret either. anne

Thank you for your comment, Anne. Margaret was a much loved sister in Arthur Llewelyn Davies’s life; they were very close being only 16 months apart and she was absolutely devastated when he died, especially as it was so close to the drowning of their younger brother, Theodore. But I can see, from a playwright’s point of view, that in the cast of must have characters, she comes pretty low down. All the same, she was an important woman in her own right and it shows me how much this new book on MLD is needed!