A day or so ago I visited the British Museum – the first time for months. Of course, I had to book a timed slot, wear a mask, make sure I used the hand gel and so on; and we were only allowed on the ground floor, so I had a choice of things Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, or Middle-Eastern. I decided to take a look at the Parthenon Frieze. I was particularly interested in the south frieze reliefs depicting a sacred procession with priests leading heifers to be sacrificed. One relief in particular, shown below, is supposed to have inspired the poet, John Keats’ Ode to a Grecian Urn.

The south frieze with the heifer

As the cloakrooms were closed, I couldn’t leave my jacket anywhere and I had to keep hold of my handbag, camera, notepad, pen, and the PVC bag which held my too heavy umbrella. It was a nightmare. I kept dropping my note pad and pen, the PVC bag, held in the crook of my arm, weighed me down and I wasn’t at all happy with my photos which were either grainy, or lop-sided or both.

However, praise be, the photo with the heifer came out well, so I thought I’d start there. So what’s going on? And why is it significant that the heifer (a female cow who has not yet had a calf) is exhibiting signs of distress, stretching her neck and ‘lowing at the skies’. She is one of a number of heifers in the religious procession and she’s not the only one to express her displeasure.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest

Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands dressed?

So wrote John Keats in his Ode on a Grecian Urn. In 1817, Keats published his first book of poems which, alas, went unnoticed by the critics. To cheer him up, his friend, the artist Benjamin Haydon, took him to see the newly-arrived Elgin marbles which had been hung in the temporary Elgin Room in the British Museum.

In the picture by A. Archer below, we can see the great and good of the artistic establishment looking at the marbles. Benjamin Haydon stands on the extreme left, holding a red book. The statues are lying all over the place. The frieze is on the wall at head height but other bits, like the horse’s head belonging to Selene, the moon goddess, are lying on the floor.

The Temporary Elgin Room at the British Museum, 1817, by A. Archer, courtesy of the British Museum.

It was essential that the animal going to be sacrificed consented to its own death; the heifer must walk peacefully and quietly. If the robed priests leading her couldn’t quieten her down, then the sacrifice couldn’t take place.

You will notice that the heifer’s flanks aren’t dressed with garlands; nor was the altar green – that bit was poetic licence on Keats’ part. However, we now know that the frieze would, originally, have been painted.

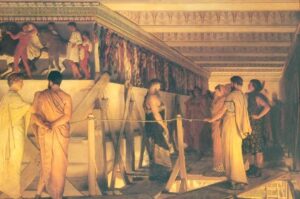

Phidias and the frieze of the Parthenon by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1868 (detail) courtesy of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

The Victorian painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema specialized in depicting the Classical World (he was known for his brilliantly painted marble) and the latest research showed that Classical statuary, including the Parthenon friezes, were originally painted. In the picture above, Phidias: architect, painter and sculptor, became the artistic director of Pericles’s building programme. Here, he is standing on the scaffolding in front of the frieze which is being sculpted, and showing important visitors around.

Pericles, a Roman copy of a Greek original

Phidias, born around 500 BC, was the contemporary of the great Athenian statesman, Pericles, and helped him in his mission to turn Athens into one of the wonders of the Greek World. Phidias, under Pericles, embarked on a massive building programme which included the Parthenon itself, with its colossal (12 m high) statue of its patron goddess, Athene, richly decorated with, gold, ivory and other precious materials and, of course, the friezes.

As you come up to the temple steps, you are met by two lots of columns. The outer row of columns support a pediment with a row of metopes (individual sculptural reliefs) immediately underneath it. Climb a few steps more and you come to a second row of columns which support the friezes I want to talk about. Actually, given their height above the ground, it’s difficult to see how anybody could have had a clear view of them in antiquity. The frieze itself is 99 cm high and 160 metres long and goes round the north, east and west sides of the building.

East frieze: young women taking part in a sacred procession

Here, the girl leading the procession is holding a thymiaterion, a cone-shaped object on the end of a short pole, which is for burning incense. It’s a bit like a joss stick; the maiden lit the perforated cone at the top and the sweet-smelling smoke drifted over the sacrificial proceedings. The girls walk single file, all standing straight and equally spaced – they are obviously used to the ceremony – the delicate folds of their draperies give a feeling of serene but purposeful movement. The girls’ left arms are modestly wrapped inside their drapery folds but, in their right hands, they each hold something: the smouldering thymiaterion on its pole, there to scent the air; a ewer, a jug, a bowl – objects they will need for the ceremony.

What is interesting about the frieze is that quiet scenes, such as the one above, alternate with other scenes indicating urgency.

South Frieze. A group of horsemen riding to the right

The group above shows three horsemen on their galloping horses. Their distinctive manes show up well, almost as if they’ve been given a Mohican haircut. The riders here are three abreast (otherwise the complications of which legs belonged to which horse would be too confusing). The riders are bare-headed but they wear body armour over a short tunic. They are wearing calf-high boots. The horses had bridles – and you can occasionally see holes around the horses’ muzzles which shows where the bronze reins were once attached and there were no saddles or stirrups.

What are they doing? Where are they going? They have no weapons so they can’t be going to war.

North frieze – more space between the horses

Here another group of horsemen are more loosely spaced out and galloping in the opposite direction, to the left. The sculptor is obviously not the same person – you can tell by the chopped horses’ manes, and the horses’ bodies are, perhaps, less detailed. The rider in the centre is sitting back and looking over his shoulder at the man behind him. He is wearing a cloak, you can see its folds rippling in the wind, but he doesn’t seem to be wearing much else. It’s a less frenetic scene, there’s time to lean back and have a word or two with a friend.

North frieze: the riders are heading left

Here the riders are dressing differently again. The rider in the centre with his right arm raised almost as if he’s going to throw something, is wearing nothing except his mantle, but the rider immediately behind him is wearing a distinctive cap with ear flaps, which resembles a Thracian cap. It was not the fashion at the time to depict people as individuals, but rather as types: the ideal youth, say. You can see the holes for the bridles quite clearly at the top of the two front horses’ mouths.

The North frieze; the cavalcade sets off

I’m ending with what is, in fact, also the beginning. What is happening? The horse on the extreme left is half rearing as if anxious to be off, his owner, standing in front of him is raising his left arm as if gesturing them to get the cavalcade going. But, curiously, he himself doesn’t seem to be at all ready – he looks as though he is wearing nothing at all but, on closer examination, there is a cloak round his neck, its folds are flaring out behind him. His left hand may be holding the horse’s bridle – it is very near his horse’s muzzle.

The horse behind is standing stock still; it must be the only horse in the entire frieze with its legs straight! It, too, is standing as if unwilling to move. But the viewer’s attention is, instead, drawn to the man and his servant at the extreme right. The man is fully dressed; he wears a tunic; he has knee-high boots, and he is patiently allowing his young servant to tie a girdle round his waist. The young boy is standing very close to his master, perhaps feeling awkward, as he fumbles with the girdle. It looks as though the entire procession is waiting for the young servant to finished getting his master ready – and then the whole procession can set off.

So what happened to the glorious Parthenon?

It’s a sad story. Some of the statues were destroyed or defaced by fanatical Christians in early Christian times, and the statue of Diana was taken to Constantinople as a museum piece where it was destroyed by fire. The rest of the building, however, survived as a church, which gave it another 1000 years of life since its creation.

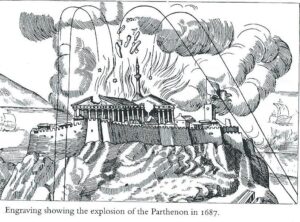

In the 15th century, the Ottoman Turks added Ancient Greece to their empire and the Parthenon became a mosque which kept the Parthenon standing and in good condition. Then, in 1687, the Venetian army laid siege to the Acropolis, the hill on which the Parthenon stands. The Turks decided to store their gunpowder inside the Parthenon, assuming that the Venetians wouldn’t deliberately aim at so admired a monument. Alas, they were wrong. On 26th September, at about 6.30 pm, a Venetian bomb ignited the gunpowder. The picture above shows what happened. The central part of the long sides of the temple were blown out and the east side totally destroyed.

Fortunately for posterity, in 1674, Jacques Carrey, a Flemish artist, drew the Parthenon, both the building and the sculptures which were largely still in situ, so at least we know what was once there and how the figures were placed. Thirteen years later, the Parthenon was largely in ruins.

Elizabeth Hawksley

‘Highland Summer’ is now available as an e-book

Highland Summer

Please share this page...

We visited the British Museum on Friday and had a day of better weather so I was not juggling an umbrella and my pictures came out well. With fewer visitors and a directed walk it is easier to appreciate all of the artifacts on display. We visit some old favourites. I am particularly fond of the horse of Selene from the Parthenon whose head is so well preserved and Bob has a soft spot for the Roman copy of the Crouching Venus. Her beautifully elegant hands must be an C18 repair. Such long slender fingers cannot have survived from antiquity.

When you look at the Parthenon frieze it is so dynamic and the procession seems to unscroll before you like a newsreel or bande-dessinée. It feels like a direct channel to an earlier age.

Thank you for your comments, Pauline. I’m glad you had a good experience – and I daresay it was helped by a more modern camera than my old digital one!

It’s amazing statuary and I’ve never seen the frieze before, especially this close up. However, I have to say that the Elgin Marbles are forever ruined for me as a serious piece of history by the immortal line – which as a fellow Heyer afficionade I am sure you will recognise – “Dash it, they’ve got no heads!”

I loved your Heyer quote – it must be Freddy Standen speaking. I considered quoting Lady Bridlington who says, ‘Arabella, my love, I daresay you are quite tired of staring at all these sadly damaged bits of frieze, or whatever it may be called – not but what I declare I could feast my eyes on it for ever – ‘ but decided against it on the grounds of bathos!

I love the British Museum. Annoying that you had to cart your belongings around with you, Elizabeth and I don’t suppose the cafe was open? It’s been a while since I visited, but going to look at favourite exhibits is always fun. The Elgin Marbles are beautifully carved, but I have to confess they don’t really “do it” for me. I did find the life-size reconstruction they have at the Acropolis Museum in Athens interesting though as it gives you an idea of the impressive scale of the temple decoration, it shows how all the metopes and frieze panels were placed – there are a lot of gaps of course.

Alas, Gail, neither of the cafes nor the restaurant are yet open. The British Museum also has the metopes in the correct order – where they exist; and each section of the frieze is correctly placed and numbered, though, of course, some of it is in Athens, or occasionally in Rome or Vienna.

It is a little sad to think of how many masterpieces from antiquity must have been destroyed over the centuries because of conflict.

On the other hand, conflict drives the story telling that informs the content of the various masterpieces.

If we could restrict violent conflict to the stadium then I think we’d be a lot better off.

You are quite right, Huon – a very thoughtful comment, if I may say so.