2020 is the 25th anniversary of the passing of the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, an act set up to create a level playing field to enable all, no matter what their disability, to live a full life with the same opportunities as everyone else. The fight has been a long one, and it’s not over yet.

Dr Francis Campbell top left, the Royal Normal College for the Blind on the right

Today I’m jumping back over a hundred years to 1891 to look at an article by Edward Salmon, illustrated by John Gülich from The Strand Magazine called How the Blind are Educated about the remarkable Royal Normal College for the Blind set up by two philanthropists, Dr Armitage, and his friend, the remarkable Dr Francis Campbell in 1872.

Dr Campbell (1832-1914), an American who lost his sight in an accident as a small boy, was a passionate believer in the value of a well-educated mind in a healthy body. (When he developed consumption, he defied medical advice to lead a quiet life, and set out to climb Mont Blanc – becoming the first blind man to do so.) He was determined to set up a College for the Blind, open to both sexes and all ranks for those whom he felt would benefit from the College’s training which aimed to create self-confident and self-supporting adults.

It is obvious that Mr Salmon was given a thorough briefing by the energetic Dr Campbell, who told him: ‘The determination to conquer obstacles is the only thing which will make a two-legged creature a (grown up) man or woman … determination is only possible to a vigorous and healthy mind (which) can only come from a vigorous and healthy body.’

Mr Salmon was obviously impressed: ‘The outcome of the adoption of such ideas is that the boys and girls at the Normal College, like Dr Campbell himself, are self-reliant, cheerful and healthy and, seen trotting about the beautiful grounds of the College, no-one would ever think they are sightless.’

In 1872, The Royal Normal College for the Blind was set up in Upper Norwood in south London, near Crystal Palace. (‘Normal’ is the American term for a teacher training course.)

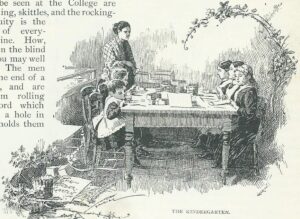

The Kindergarten

Mr Salmon was shown the kindergarten for boys and girls from 5 to 13 with a group of girls interweaving slit paper to be used as decoration for baskets and other things. The teachers are American – and sighted. Nearby is a glass case containing clay models of various natural objects: pea-pods, buttercups and even a dog, all made by the pupils themselves. What interested me was that the children are noticeably expressionless, as Sheila Hocken pointed out in her delightful book Emma and I about her guide dog, and what happened when an operation gave her back her sight. People blind from birth, or blinded very young, tend not to have much facial expression. Expression comes with sight – babies imitate their parents and other people. The artist, John Gülich, has obviously noticed this, too.

At 14, the children moved up to a proper school where they learned music, mathematics, geography, and so on. The physical training continued.

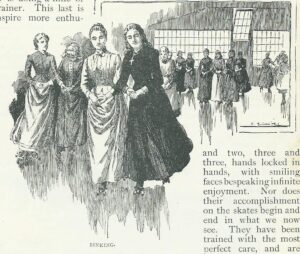

Roller skating

Mr Salmon was impressed by seeing a dozen girls roller-skating in a largish room, 24 x 18 feet. ‘Here are a dozen or more girls moving rapidly round and round on the tiny wheels. They touch neither the wall nor the seats by the wall, whilst the immunity from collisions induces one to exclaim: “Surely we are not in the presence of the totally blind…” We are indeed. But how is it those sightless young ladies move so rapidly, and yet with a safety and precision which might make their seeing sisters envious of their skill? Solely by instinct and practice.’

And, he noticed, they were smiling. They were obviously enjoying themselves. Note the long skirts worn by the young ladies; girls under seventeen would have worn calf-length skirts.

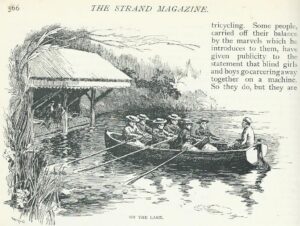

On the lake

And the girls don’t only skate – they can row, too. Dr Campbell had a boat constructed which held eight rowers and a sighted teacher on the stern seat. The oars are long and evenly spaced – the girls have obviously been properly taught. I like their jaunty boaters. Mr Salmon doesn’t tell us but I bet the girls can swim, too.

Cycling – note the milestone in the foreground

Dr Campbell invented the eight-seated bicycle, or, more accurately, four two-seater tricycles locked together, which carried seven sightless riders with a sighted helmsman at the front. The doctor’s determination to ensure that the girls were healthy, competent and knew what they were doing is evident. And, as Mr Salmon continued: ‘this machine may often be seen on the country roads of England carrying its seven sightless riders. They go out for a twenty mile spin, have tea at a country inn, and come back tired and ready for bed.’ It sounds fun – providing the weather is good. And the milestone emphasizes that the young ladies are strong and healthy and quite capable of cycling for twenty miles.

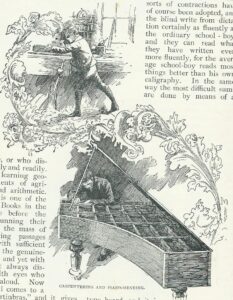

Carpentry and piano-mending

But what are the boys trained in? Dr Campbell was equally resolved that the boys should all be trained to a professional level. He wanted them to be independent and capable of earning their own livings. The double illustration above shows the boy in the top illustration learning carpentry and the boy underneath is learning to repair a piano.

Messrs Broadwood, the piano makers, were very supportive towards the College. They decided to make Dr Campbell a special model piano which could be taken to pieces and put back together so that the pupils could learn how it was constructed and how to repair it. The boys learnt how to tighten a wire, or replace it, and they also learnt to tune pianos. Proof of the boys’ excellent teaching was that one of the employees at Broadwood’s was an old pupil of Dr Campbell’s.

Musica: Lux in Tenebris (Music: Light in Darkness) reads the legend on the banner beneath the lady at the piano

Music, was, of course, one of the principal means of making a living for the blind, whether as a piano tuner, repairer or teacher. And concerts, as the illustration of a concert above shows, was one of the ways the College made an income.

But, alas, there was still plenty of prejudice against offering College pupils proper jobs in the outside world. As Mr Salmon put it, ‘All he asks on behalf of his pupils is a fair field. He wants no favours.’

Here is just one example. When Dr Campbell wanted one of his pupils to compete for the position as organist in a large church, ‘The authorities declared it to be impossible that a blind person should hold the position, and, to make sure it was impossible the candidates would be called upon to play any two tunes in the hymn book which any two people in the congregation might select.’

Dr Campbell got to hear about this underhand move. He got hold of a list of the most popular hymn tunes at the church, translated the scores into Braille, and his pupil learned them by heart.

Let Mr Salmon finish the story: ‘The first hymn called for was played by the blind candidate not merely as it was written, but with variations. The authorities marvelled but said it was chance. The second was called, and still the blind man was ready. “It’s a miracle” was the exclamation, but the blind man won, and holds today, the position competed for.’

I could not but agree with Mr Salmon that Dr Campbell had to fight a mountain of prejudice, ignorance and injustice – far greater than his youthful ascent of Mont Blanc. The Royal National College for the Blind is still going strong and is now in Hereford, where it has been the recipient of many awards. https://www.rnc.ac.uk

Eventually Dr Campbell took British Nationality, and was knighted in 1909 by King Edward VII for his ground-breaking work on behalf of the Blind, and quite right, too.

In my view he ought to be in the Dictionary of National Biography; he certainly deserves it.

The Royal National College for the Blind

© Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

This is a very inspiring and uplifting article Elizabeth. Thank you very much for sharing.

The world could do with a few more Sir Dr Campbells I think. I wholeheartedly agree with the doctor’s views on determination and the relationship between a healthy mind and a healthy body.

I was half expecting to read that the Royal Normal School had shut down in the 70s or something; so I’m delighted to hear that it’s still around.

Thank you for your comment, Huon. I’ve just added the College’s current address and website, and noted that Dr Campbell was knighted by King Edward VII for his ground-breaking work on behalf of the Blind. By the way, a knight becomes Sir plus first name plus surname. Any other titles, such as Doctor, Admiral etc go first. So Dr Campbell became Dr Sir Francis Campbell and would have been addressed as ‘Sir Francis.’

What a splendid, joyful blog! A very brave and determined man who evidently instilled the same qualities in his pupils. How lucky they were to have found him. It would be nice to think that the Strand article generated lots of donations for the school.

I agree, Jane, and that reminds me – I meant to check on the Royal National College for the Blind’s current whereabouts and its website and put them both in the post. Also to include the fact that Dr Campbell was knighted by King Edward VII for his ground-breaking work on behalf of the Blind.

I have just done so.