The Strand Magazine of June 1891 took its readers to The Home for Lost Dogs which had been started some 30 years before in Miss Mary Tealby’s scullery in Holloway. Miss Tealby’s charity soon outgrew its humble beginnings and, by 1891, the Battersea Dogs’ Home was established and popular enough for Mr George Newnes, The Strand’s editor, to send one of his reporters to write about it, and the artist Mabel D. Hardy accompanied him as illustrator.

‘To the Home for Lost Dogs’ by Mabel Hardy (1868-1937)

Miss Hardy and the Strand reporter were shown round by the secretary, Mr Matthais Colam, who began by giving them the statistics. In 1890, The Battersea Dogs’ Home had offered temporary accommodation for over 21,593 lost dogs: homes were found for 3,388; 1771 were restored to their owners; and 1617 dogs had new owners once the Home had checked that the dog would be properly looked after. That still leaves an awful lot of dogs … of which more in a moment.

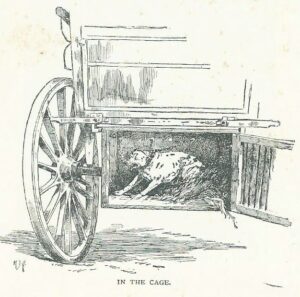

The cage for unmanageable dogs in the van which brought lost dogs to the Battersea Dogs Home, by Mabel Hardy

Miss Hardy and the Strand reporter were due to begin their tour in the Receiving House, but they were held up at Battersea’s red gates when one of the Home’s special collecting vans with about 30 dogs inside arrived. Miss Hardy got out her sketch pad. The van was custom-made with two floors, the bigger dogs went below with the smaller dogs occupying the top floor. There were iron rings and chains around the sides to attach the animals; and, at the bottom of the van, between the two back wheels there was a cage for a seriously troublesome dog, or even a mad one – rabies was not uncommon.

Of course the public also brought in dogs – sometimes as many as 500 a day. There were dogs of all sorts: from a pampered King Charles spaniel which had probably escaped from a drawing-room in Belgravia, to a ferocious bulldog which suggested ‘pugilism and Whitechapel’ to the reporter. We will see later that Whitechapel was an area of London with a notorious reputation.

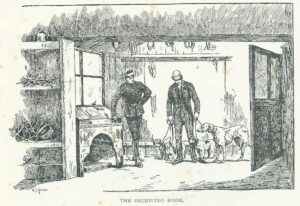

The Receiving Room. Each dog must be registered and examined by the vet, by Mabel Hardy.

The Receiving Room was divided into seven sections named after the days of the week. First, the dogs were divided by sex, and then they were all examined carefully by the veterinary surgeon, Mr S. J .Sewell. Any dog with rabies would be destroyed immediately; other ill dogs were treated kindly and humanely and their ills seen to; those dogs who were incurable went to the ‘condemned cell’ but more of that later.

There were, of course, plenty of stories to be told – some even featuring royal dogs: the Duchess of Teck’s dog was brought in and, of course, restored to its royal owner (the Duchess was the mother of Princess Mary of Teck, the future wife of the future King George V). After a suitable lapse of time, unclaimed dogs could be bought, some of whom went on to win important prizes at dog shows for their new owners. One dog, a boarhound called Bluebeard, became famous for continually getting lost; he was collected by his owner four times but, somehow, always managed to escape and find his way back to Battersea – the last time tapping with his paw at the Battersea entrance to be let in. He then returned to his previous kennel. Eventually, his owner sent Bluebeard into the country where he settled down.

The reporter was told, ‘Even at the Dogs’ Home many a romance might be found.’ Unfortunately, he didn’t share them with us!

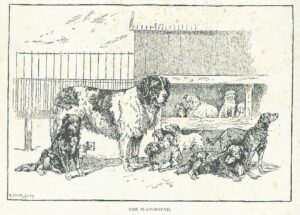

The Playground. Note that some of the dogs at the back are sitting on a ledge in the shade, by Mabel Hardy

Miss Hardy and the reporter then moved on to the kennels: ‘fine, light, airy and well-built places’. There were playgrounds for the bigger dogs (retrievers, Scotch collies, greyhounds, even ‘carriage dogs’) where the dogs frolicked about and enjoyed themselves. The playgrounds had fountains to play in, and wooden shelters from the sun in summer, or from ‘inclement weather’. There were smaller playgrounds for the smaller dogs.

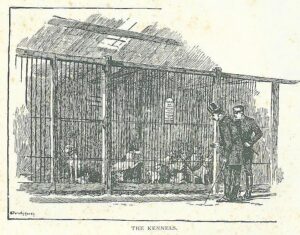

The Kennels. A hopeful visitor looks for his lost pet, by Mabel Hardy

There were certain rules about collecting a lost dog. The owner who recognized his or her dog had to go with the keeper to the playground or kennels where the dog was. The dog was then chained to the railings and the keeper watched the meeting between dog and owner. Usually, there were usually frantic barks and wagging of tails from the dog and cries of joy from the owner. But that wasn’t enough.

Dog stealing was a lucrative crime and keepers had to be aware of the various scams they employed. For example, a thief might have his eye on a dog with an expensive collar – a dog could be held for ransom (the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog Flush was kidnapped for ransom). A canny keeper with suspicions could exchange an expensive collar for a more ordinary one before showing the dog to the ‘owner’. The would-be thief’s bluff would then be called and he’d be lucky to make his escape. (Note that the reporter suspected the thief came from Whitechapel.)

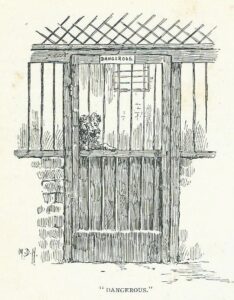

‘Dangerous’. This poor dog may have rabies and his stay will be a short one, by Mabel Hardy.

There was a special shed for puppies born at the Dogs’ Home; and another shed labelled ‘Dangerous’ for a dog which needed to be kept apart from the other dogs.

The dogs ate two tons of biscuits and meal every fortnight. At 6 o’clock they were bedded down for the night with clean straw and sawdust, and, every hour, the night watchman made his rounds to see that all was well.

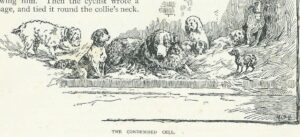

Officially the Infirmary: in practice, the Condemned Cell by Mabel Hardy

Then came the most unpleasant duty of the day, that of killing those dogs who had been condemned by the vet. Those dogs were kept in the Infirmary. The poor dog on the left certainly looks in a bad way.

The reporter wrote: ‘It should be said that a dog is never put to death unless it is past all cure, and, further, that the means employed are as quick and humane as scientists have discovered.’ He continued: ‘the most painless way of causing death was by the use of narcotic vapour.’

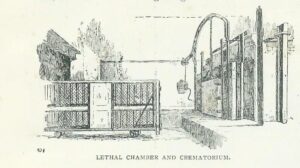

The cage with wheels (the Lethal Chamber) and the Crematorium by Mabel Hardy

What happened was this: The condemned dogs were put into a huge cage on wheels, ten feet long by four feet deep, which was divided into two tiers. When all the dogs were safely inside, they were wheeled into the Lethal Chamber. ‘The door to the lethal apartment is unlocked and opened and the cage is run in and secured. The doors are closed. Here it remains for some six or seven minutes, during which time, the chamber is charged with carbonic acid gas, and a spray of chloroform is pumped in, which the dogs immediately inhale. This process of bringing about all that is needed is not strangulation or suffocation, but is essentially, a death sleep.’

The Dogs Home also had two smaller lethal chambers for use when a dog needed to be destroyed immediately.

The crematorium was immediately opposite the Lethal Chamber – a white brick structure with a 65 ft. high chimney. Five or six hours after the dogs had been killed, their bodies were put into a 10 x 9 ft. space above and quite separate from the crematorium’s coke furnace. By the morning, all that remained were a few charred bones which were put into a dozen or so sacks and sold to soap-makers.

Every week, on average, three hundred dogs were killed.

The reporter and Miss Hardy’s tour ended with a quick look at the ‘Reading Room’ – though he doesn’t say who this was for – the Office which contained rows of immense ledgers with the records of all the dogs who had ‘enjoyed the hospitality of the Institution’, and the Boardroom where there were framed testaments in display from Her Majesty the Queen, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge, all of whom were patrons of the Home. (I wondered if this still applies in the present century.)

A prized letter from Queen Victoria reads: ‘The objects of your association appear to be deserving of the greatest sympathy and commendation; and your solicitude for the welfare of dogs, the friends of man, who have showed so much zeal, fidelity, and affection in the service of mankind, is the fitting complement of the charity which strives to comfort and succour the unfortunate and afflicted members of our own race.’

The Queen was noted for her love of dogs.

Dog collar, muzzle and whip, by Mabel Hardy

The reporter was obviously much impressed – and there is much to praise. I noted, however, that Miss Hardy’s contributions ended with a picture of a dog’s muzzle, a whip, and a large dog collar with a strong chain which was obviously intended to be attached to railings. She may have felt more ambivalent.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Twitter: @Hawksley_E

Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B08VHCFFKD/

Please share this page...

Another interesting post. Thank you.

Thank you, Jan. Part of me applauded the Battersea Dogs Home’s ‘tell it like it is’ approach – they obviously see no need for euphemisms; but I couldn’t help but wince slightly at them selling the dog bone remains to soap-makers. Illogical, I know, but there we are. It must have cost a fortune to feed all the dogs and I’m sure they needed the money.

I read your article with interest because we have just re-homed an adorable puppy from Battersea. My daughter is friends with someone who works there and she kept an eye out for a suitable replacement for our beloved dog who died in March.

My experience is that Battersea is just as meticulous and caring of their animals. Maisie came from a couple who thought that at least one of them would be working from home permanently. When they discovered this not to be the case, they took the difficult decision to re-home her rather than let her go through the distress of being left at home all day.

She was examined by the vet, vaccinated, chipped, groomed and spayed before they would allow her out. They also tested her for her tolerance of other dogs and cats to ensure that she went to the right home.

For most of this year, all their animals have been sent out to foster homes because of potential staffing difficulties, most of the staff taking at least one animal.

The dedication apparent from those early years still lives on in the staff today and I salute them!

Thank you you for your most interesting comment, Penny. I’m very impressed by the dedication and care of those who work at the Battersea Dogs Home both now and back in 1891. And I take my hat off to Maisie’s former owners for their brave decision to re-home their beloved dog. Will Maisie be going back to her original owners, one the pandemic is over?

What also struck me was how thorough the Battersea Dogs Home staff are about dogs coming in being examined by a vet, vaccinated, chipped, groomed and spayed before any decisions are made about the dog’s future.

Your comment has added a huge amount of interesting and important information to my post and I’m very grateful to you for sharing your thoughts.

I’m also very sorry to hear that you lost a much-loved dog last year.