The story of Judith and Holofernes from the Old Testament inspired a number of Renaissance artists, Cristofano Allori and Artemisia Gentileschi among them, to paint the beautiful Jewish heroine, Judith, chopping off the head of Holofernes, the Assyrian General who had been sent by King Nebuchadnezzar to conquer Palestine. Sex and violence, as ever, proved to be a popular mix – and very sellable.

I’m starting with a brief resumé of the story. Judith, a beautiful Jewish widow from Bethulia hatches a plan to kill Holofernes whose army is pitched nearby. She takes a lot of trouble to look beautiful: she removes her widow’s weeds, takes a perfumed bath, and adorns her hair. She dresses in rich and beautiful clothes, and wears expensive earrings, necklace, rings and bracelets to emphasize her status. (She is definitely not a whore.) Her slave gets together enough food and drink to last them both long enough for her plan to come to fruition. All the food is prepared according to the Jewish tradition. (She doesn’t want to be poisoned.)

Her pitch is that she had been told by God that Holofernes will triumph because the Jews have offended Him by breaking His laws. She and her slave will sleep in the Assyrian army’s camp at night but, during the day, she will go out into the valley and pray to God who will tell her when the time is ripe for Holofernes to attack.

We can see how beautiful Judith is in the picture by Cristofarno Allori below.

Judith and Holofernes by Cristofarno Allori, 1613

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Judith and her slave woman leave Bethulia and are soon discovered by an Assyrian patrol. Impressed by Judith’s beauty and obvious status, they promise her safe-conduct and take her to Holofernes, who is equally struck by her beauty. Holofernes’ tent has a mosquito net made of purple and gold thread, sprinkled with emeralds and other precious stones. (At this point I thought, ‘Ah! Hello!’) Naturally, he wants to sleep with Judith but decides to bide his time.

Judith follows her plan for three days and the guards become used to letting her out of the camp unquestioned.

On the third evening, Holofernes holds a banquet in her honour – he intends to seduce her – and, we are told, drinks more wine than he has ever done before. Judith, as usual, eats her own food, prepared by her slave according to Jewish dietary requirements. Holofernes falls into a heavy, drunken sleep.

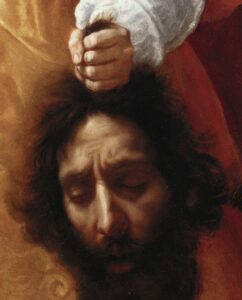

Allori’s Judith holding the sword with which she has just severed Holofernes’s head. We cannot see the sword’s bloody blade, only the hilt.

Judith seizes his sword which is hanging from a bedpost, beheads him quickly and without fuss, and gives the head to her slave to hide in the now empty food bag. Judith also takes the be-jewelled mosquito net – and they both leave the Assyrian camp without a problem.

Once back in Bethulia, Judith is greeted as a heroine; the Jews defeat the Assyrians and everything ends happily – for Judith at any rate.

Another view of Allori’s painting of Judith and Holofernes

I was absolutely spellbound by this painting. It packs a real punch. Judith, is beyond question, a very beautiful woman, magnificently dressed in a golden damask dress and a cloak with a crimson lining. She holds the severed head of Holofernes in her left hand, grasping it by a matted tuft of his hair as if it weighs nothing. In her right hand she holds Holofernes’ sword – the business end of which is out of the frame. Holofernes’s head is a self-portrait of the artist, Allori.

We note that there isn’t a single drop of blood anywhere. If the sword is dripping blood, we don’t see it. Her golden robe isn’t stained, and Judith herself looks calm and poised. If the flare of the crimson lining visible against the black background is a metaphor for the blood from Holofernes’ severed arteries, it’s plainly not something that Judith is worried about. Though I confess that the more I looked at it the more it disturbed me.

Judith herself is a portrait of Allori’s mistress, Maria de Giovanni Mazzafirri, and we can believe that their relationship was tempestuous – and it certainly made Allori very unhappy. She spent his money and constantly made him jealous, and we can see his distress in his deep frown and taut features. Possibly, it was Allori who had paid for Maria’s stunning dress – and it must have cost a packet.

Self portrait of Cristofano Allori, 1606, Museo Capodimonte, Naples

Allori’s dates are 1577-1621, and he was 29 when he painted the picture above. It is undoubtedly the same man, and, in reality, he is quite good-looking. He has thick hair, carefully cut and shaped; his hat looks expensive, and his coat is fur-trimmed. He, too, like his mistress, cares about how he looks and dresses.

The portrait of Judith with the head of Holofernes is seen from the point of view of Holofernes, that is, Allori himself. He is saying: This is how you’ve made me feel. I no longer have a body, or hands to paint with, or blood; you have drained me of everything. I am an empty husk. The more I looked, the more I could feel his distress.

Portrait of Abra, the mother of Maria Mazzafirri as Judith’s maid

And what about the older woman standing behind Judith, who is she? She is Abra, Maria Mazzafirri’s mother. Apparently, Allori blamed Abra for her part in souring his relationship with her daughter, but that is not what I get from Abra’s face, as she peers over Judith’s shoulder. She looks grieved and deeply concerned. I find it difficult to believe that the Maria in the picture took any notice of her mother at all – or, indeed, anybody else.

Judith and Holofernes (1612-1613) by Artemisia Gentileschi. The Uffizi Gallery, Florence

I want to move on now to another portrait of Judith and Holofernes, this time by Artemisia Gentileschi which, interestingly, takes the opposite point of view from Allori.

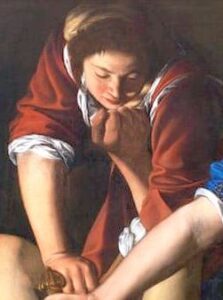

Judith and Holofernes (1612-1613) by Artemisia Gentileschi. We can see Judith’s concentration as she sets to work.

It’s the same story, and the same moment within the story, but what a difference! This time, we are not seeing Holofernes’ death from his own point of view, but from Judith’s. Unlike Maria Mazzaferri’s Judith, where she has no trouble at all in killing Holofernes, Artemisia’s Judith has a real struggle on her hands. She’s got his head twisted to the exact angle she needs and she’s just plunged Holofernes’ own sword into his neck. Her other hand is grasping Holofernes’ hair to hold him in place. We can see blood spurting everywhere. She’s leaning back, partly to see what she’s doing, but also, perhaps, to protect her dress but it’s no use. We can see flecks of blood everywhere –not only at the top of her bodice but also on the flesh of her neck.

Judith’s maid is equally determined to play her part.

Her maid, too, plays her part by preventing Holofernes’ arms from pushing Judith away. Both women’s muscles are straining and we notice that they both rolled up their sleeves before starting the job. From their determined expressions, we can see tell they mean business. Holofernes is a strong man, they will need every ounce of strength they possess to overcome him.

Holofernes’ eyes are open – he is alive and knows what’s happening – which heightens the horror.

We know that Artemisia was raped, age 17, by Agostino Tassi, an artist friend of her father, Orazio Gentileschi, who himself taught Artemisia to paint. She managed to wound Tassi during her struggle against the rape. During the resulting trial, Artemisia herself was tortured – to test whether she was telling the truth – but she held firm and yelled out her outrage at the way Tassi had treated her.

What stands out about this painting is that both Judith and her maid are proactive. You can see from their grim tightened lips that they are strong women.

Allori’s painting says to his mistress: this is what you have done to me. Artemisia’s painting says: this is how it feels to be helpless, but I, Artemisia, am not helpless and here is the proof. No-one will forget my painting.

Both paintings are equally rewarding for viewers, but in entire different ways. And, at the moment, they are both on display in London – or they would be if we were not in lockdown; Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith and Holofernes is in the National Gallery’s exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi, and Cristofano Allori’s Judith and Holofernes is at the Queen’s Gallery in the wonderful Masterpieces from Buckingham Palace exhibition. You can look at both paintings on the National Gallery and The Queen’s Gallery’s respective websites.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Judith and Holofernes by Cristofarno Allori

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

https://www.kobo.com/gb/en/ebook/frost-fair

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/1056557

(Frost Fair)

Please share this page...

This is so fascinating, Elizabeth. Thank you.

I have always wondered what in her past drove Judith and also how she would have felt afterwards. I overmuch doubt whether either of these Judiths would have suffered agonies of remorse.

I agree, Sophie. We must not forget that both Artemisia and Maria must have been, in different ways, subject to constant reminders of the lack of respect for their sex. Maria made her living by being the mistress of a rich artist, but what other options did she have? We can see that she had an excellent dress sense – but she could never have become an independent 17th century Coco Chanel.

We know that Tassi was convicted of the rape of Artemisia; and fined and exiled – which sounds like a victory- but he never paid the fine, nor did he leave Rome. It was Artemisia who was hastily married off and sent to Florence – admittedly she did very well there, but that’s not the point. The status of women remained the same.

I find it interesting that one painting barely shows any trace of the violence and the other shows just about every possible part of it.

This story seems to have attracted the attention of two very different yet similarly tortured artists.

I absolutely agree, Huon – it’s what made me think that a compare and contrast look at two completely different paintings of the Judith and Holofernes story might make an interesting blog! And I think it has.