One of the most splendid exhibits in the British Museum is undoubtedly the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial and its astonishing treasures, dating from the 7th century A.D. which was excavated 1938-9, as the country prepared itself for war.

The Bronze Helmet – fit for a King?

Under the direction of Mrs Edith Pretty, the owner of the Sutton Hoo estate in Suffolk, the various burial mounds began to be excavated. As expected, most of them had already been plundered but, what became known as Burial Mound I, was miraculously preserved. In 1938, Mrs Pretty ordered Basil Brown, a self-taught archaeologist, geologist, astronomer and much more, and two trusted helpers to begin digging.

Mrs Edith Pretty (I883-1942) One of the British Museum’s greatest benefactors (photo courtesy of the D.N.B.)

Brown was a man of great intelligence, unswervingly loyal to Mrs Pretty, entirely self-educated and discreet. Once he had begun to uncovered the iron rivets which were all that remained of ship’s shape, he recognized at once what they signified and he packed bracken over the exposed surfaces for their protection before turning his attention to exposing the sand stains which represented all that was left of the rising stern of an enormous buried ship. He soon had to widen the excavation as the ship’s full size gradually became clear.

Basil Brown (1888-1977) (Photo courtesy of the D.N.B.)

Bear with me, dear reader; all too often important people in the story – if female and/or the working class – are implicitly viewed as secondary to the main action. But not on my watch.

Photograph of the excavation, 1939, clearly showing the ship’s shape

The ship’s importance soon became clear when Brown reached the site of the burial chamber. The British Museum were called in and took over the excavations. Mrs Pretty insisted that Brown should continue to work on the ship. The uncovered treasures were carried, by Brown, placed carefully under her bed and guarded overnight by her butler and two policemen before being taken to the British Museum. (I assume that she herself slept elsewhere!)

No body was found with the treasures, probably due to the acidic soil. Modern techniques have established that a cremated body was once there.

Ornate gold belt with garnet decoration

The treasures themselves were stored in Aldwych Underground Station for the duration of the war.

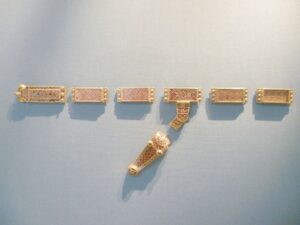

Shoulder clasps – one for each shoulder

These gold shoulder clasps, gently curved to fit the shoulder, are reminiscent of Roman military dress, and were once attached to a thick or padded garment by loops at the back. Each clasp is made in two parts, decorated with cloisonné garnets and patterned millefiori glass. Each has a central animal-headed pin featuring interlacing serpents with blue glass eyes and two interlocking boars (symbols of strength and courage). Setting gems in gold on a curved surface takes immense technical skill.

Replica of the bronze helmet from the side

Much though I love the British Museum, I have to be honest and say that the display of the Sutton Hoo treasure is disappointing – which may be due to the after effects of Covid when normal cleaning or adjustments of the lighting couldn’t be carried out. The photograph of the helmet wasn’t easy because of the intrusive inclusion of bars of blue light and the peculiar scaffolding behind it. Eventually, I managed it but I had to lighten the photograph considerably.

The hanging chain and the cauldron

The dark against dark problem recurred. The picture above was so dark that, when I got home, I could scarcely make out what it was I’d photographed – which turned out to be a replica of the cauldron – the 3.5 metre chain hung from the ceiling beam which obviously suggested that the ceiling of the burial chamber was extremely high. The information board included a small sketch showing how it may have looked. Unfortunately, the cauldron and chain were squashed into a corner and surrounded by scaffolding holding the chain.

I’d have loved a picture, or even a model, of what the 7th century burial chamber originally looked like and where the objects were all found in the burial site. Alas, there is nothing.

Three silver bowls from a pile of ten discovered inside the burial chamber

I also had problems photographing the silver bowls. The way they were lit made it almost impossible to see them clearly. According to the information board, the three bowls’ decoration is of Christian significance. Alas, I couldn’t make it out. Was the smudge I could see a cross? I couldn’t be sure. Wherever I stood, the bowls picked up yellow light beams and flashes of white. It wasn’t my reflection – I was wearing a bright blue coat and I did my best to remove myself from sight.

Is it possible to clean the silver items? They looked very tarnished – but perhaps that, too, was the result of Covid. But, surely, modern technical wizardry could do something about the lighting.

The purse clasp

This clasp once held a leather pouch (the white bit) which would have hung from the waist. Only the gold frame and the catch survive. There are seven plaques of gold cloisonné and millefiori glass beneath the clasp. The top plaques have complex geometrical patterns and those underneath are of strange creatures.

The gold coins once inside the purse survived which enabled the archaeologists to date the burial. The latest coin dates to 625 AD so the burial obviously took place sometime after that. One source I read said that, ‘the riches of the burial as a whole suggest that the dead man was a king of East Anglia, the most likely candidate being Redwald.’

Unfortunately, nowadays you are not allowed even to mention the name Redwald (or even Rædwald) – and the signage doesn’t. Personally, I like the human touch. What’s wrong with suggesting Redwald? Surely he’s part of the story – even if only temporarily.

Aurochs’ drinking horns

These are rather splendid – though the aurochs’ horns are replicas. I wonder how much wine they could hold.

Gold buckle

This elaborately interlaced gold buckle has concealed compartments front and back which may indicate that it was a reliquary of some sort. The intricate pattern of snake-like creatures contrasts beautifully with the overall symmetry of the design.

Finely modelled bronze stag which surmounted an iron standard – a symbol of authority

In August 1939, Mrs Pretty gave the Sutton Hoo treasure to the nation – with enough funding to pay for the conservation of the objects. The donation was described as ‘the most magnificent single gift ever made to the Museum in the lifetime of the donor.’ In 1940, she refused a C.B.E. She hadn’t been well for some time and what energy she had was devoted to organizing accommodation for evacuees. She died in December 1942.

As happens all too often with regard to women’s, (and working class) contributions in fields which have hitherto been considered reserved for educated males, Edith Pretty and Basil Brown’s names and achievements swiftly faded into the background. Their entries in the Dictionary of National Biography date only from 2014 – which is disgracefully late. Both of them had interesting and worthwhile lives and they deserve to be better known.

You can access the Dictionary of National Biography with your library card. If you don’t have one, may I suggest you get one – it’s free!

Elizabeth Hawksley

I’m delighted that my Crossing the Tamar is now out in e-books

Please share this page...

Interesting, but what a shame they aren’t exhibited better.

I agree, Jan. It’s very unlike the British Museum to fall down so badly. Their new Islamic Galleries, for example, are just wonderful. I hope, as they recover from lock down, that the defects will be remedied.

Thank you for an interesting post, Elizabeth. I must admit that I have never been particularly keen on this period of history, but this exhibit does look worth a visit. I usually concentrate on the Greek, Roman and Egyptian collections but I shall definitely have a look at this one the next time I manage to get to the Museum.

Thank you for your comment, Gail. The Sutton Hoo treasures are important as they showed us, for the first time, that the Dark Ages (the 7th century) in early Anglo-Saxon times in South East England weren’t ‘dark’ at all but a sophisticated age which traded with the whole of Europe, and with top quality jewellers, armourers, and goldsmiths whose work, as shown by their grave goods, could equal anything other great civilizations had produced.

I think you should see them for yourself, when you can. You won’t be disappointed.