Room 61, in the British Museum’s Egyptian Galleries, which showcases the wonderful Tomb of Nebamun, is one of my favourite rooms. The display is created around eleven frescoes from the tomb of Nebamun, who lived in the city of Thebes (present-day Luxor) on the River Nile, around 1325 B.C. He was a middle-ranking official scribe and grain counter working at the nearby temple complex; and an important man. The frescoes were acquired by the museum in the 1820s.

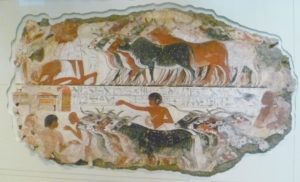

The herdsman and peasant farmers herd Nebamun’s cattle to be counted. (Photo courtesy of the British Museum)

The fresco above is a lively scene which gets across both movement and how many well-fed, quality cattle Nebamun has. At the front of the queue on the top left, several peasant farmers are kneeling, which emphasises Nebamun’s status.

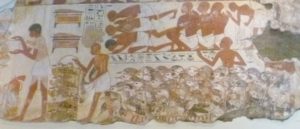

Servants herd Nebamun’s geese towards the left, where a scribe is noting everything down. Photo courtesy of the British Museum.

Notice that the peasants are prostrating themselves on the ground at the top of the fresco; they are small and darker skinned than the scribe who is holding a scroll with the results of his survey at the bottom. Everything is done to emphasise Nebamun’s importance compared with the submissive peasants.

The hieroglyphs give us the conversation, ‘move on … Don’t speak in the presence of the praised one… Pass on quietly and in order.’

Hollow glass fish bottle, possibly for perfume

As well as the frescoes themselves, Room 61 displays a number of everyday objects in the British Museum Egyptian collection which cast light on Nebamun’s life: a wooden stool, with a rush seat, and a beautifully carved back rest inlaid with ivory; a glass fish bottle, a gold necklace Nebamun’s wife might have worn, an ivory box which held cosmetics, and so on.

Ivory cosmetic box with hinged lid, depicting duck and ducklings. This might have contained mascara.

A well-to-do and important man like Nebamun would want his tomb to depict the sort of life he hoped to lead in the Afterlife, and he and his wife, Hatshepsut, took, as grave goods, the domestic objects – or small replicas of them – they would both need.

Gold necklace with lotus buds

His wife would, naturally, want her cosmetics and jewellery.

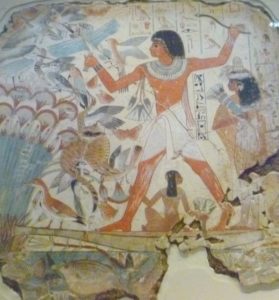

Nebamun goes hunting in the marshes

The tomb frescoes depict scenes of Nebamun’s life in the Afterlife; here he and Hatshepsut are forever young and beautiful and we can see him standing on a reed boat with Hatshepsut and their daughter standing behind on the stern. The hieroglyph tells us that he is, ‘Enjoying himself and seeing beauty.’ The fresco depicts dozens of different sorts of marsh birds; a tabby cat sits in the branches of a bush with a newly-captured bird in her claw. There is an abundance of lotus flowers and plain tiger butterflies.

Terracotta model of a poor man’s home

However, the curators of Room 61 do not let us forget what the lives of the poor were like; no pleasure trips to the marshes for them. A farmer’s home was made of mud-bricks, wood and reeds, easily washed away. In the model above, the yard is full of food – aspirational food, one assumes, rather like Nebamun’s teeming marsh. There are also some pottery vessels and a mould for making bread. We note that the pottery is unpolished, undecorated and of poor quality.

Working hand plough

A peasant farmer’s life passed in back-breaking toil as we can see from the hand plough above. The case also contains a sickle, and some very basic reed shoes, just a sole and a strap between the big toe and the next toe with and a loop round the ankle. It won’t be of much use in a muddy field.

Nebamun’s Garden in the West. Photo courtesy of the British Museum

Nebamun’s garden fresco also echoes the garden a wealthy person would have had. It has a pool teeming with fish, birds and waterlilies, and edged with sycomore figs, date palms, and dom palms, each shown at different stages of development. The sky-goddess Nut leans out of a tree to offer Nebamun a fig, and a sycomore tree speaks and greets Nebamun as the owner of the garden.

Nebamun’s feast: musicians and dancing girls. Photo courtesy of the British Museum

The fresco depicting Nebamun attending a banquet depicts the women’s band sitting on the floor with their instruments facing the viewer. Usually, figures are shown in profile, it is most unusual to see their faces. Why, I are they painted in this way, I wonder? The couple of naked female dancers to their right create a sinuous shape as they dance, and they are, traditionally, shown in profile.

From the interactive display of the inside of Nebamun’s tomb. The photo shows the inner room with the walk-in smaller room for the statuettes and altar

Nebamun’s tomb, now lost, was carved into the hillside on the west side of the Nile at Thebes. It is a long rectangular shape comprising an entrance chamber, a connecting outer room, another connecting small space, and an inner room which has a smaller walk-in space with a plinth at the end on which sit statuettes of Nebamun and his wife.

Statuettes of Nebamun and his wife, Hatshepsut

This is a space for offerings and for visitors to pay their respects. The tomb ceilings are brightly painted and all the walls were frescoed. The walls would have been roughly plastered with a mixture of mud and straw, followed by a thin layer of fine plaster to make a smooth surface to paint on. The artists would then come in to decorate the tomb to a pre-arranged plan.

Painting implements and paints

Brushes were made of twine, reeds and twigs, bound together, and colours came from various natural materials, such as stones, soot and ground minerals.

Offerings of bread, dates and figs

Underneath the last room there is a shaft going down into the rock, leading to Nebamun and Hatshepsut’s burial chamber, containing their mummified bodies and their personal grave goods.

Offerings being brought to the family tomb: servants hold desert hares and a gazelle

The burial chamber itself would have been sealed but the outer rooms were left open so that friends and family could visit and leave offerings on appropriate days. The whereabouts of Nebamun’s actual tomb has been lost but the hill side is full of holes indicating the entrance to tombs. My guess is that there would have been a janitor of sorts to make sure the place was secure, and ready for visitors.

All in all, Room 61 is a wonderful display, beautifully and imaginatively presented. It is, rightly, one of the museum’s ‘must see’ treasures.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

I was most fascinated by the paint brushes and paints. Extremely sorry for the peasants. Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose really, if in a different time, place and sphere. The gap between rich and poor never seems to close, but rather widen, if anything.

I agree with you about the paint brushes, Elizabeth. When I looked at the bundles of reeds labelled ‘paint brushes’ in the museum, they looked far too thick and clumsy to have done such delicate work as butterfly antennae, and so on. I’m rather surprised they didn’t use some sort of animal hair – hair from a horse’s mane might work.

I agree with you about the peasants. Mind you, we only have Nebamun’s word for how things were. He’s obviously going to talk himself up, after all!

It is a long time since I have seen these frescoes. Thanks for reminding me how lovely they are. I do love the BM, but sadly with my foot problems I can’t manage too much walking these days, which makes big museums rather challenging.

I’m so sorry to hear about the foot problems, Gail. The British Museum does have lifts, of course, but, as you say, such a huge place can still make visiting a challenge.

Incredible! I find it’s always worthwhile to step out of one’s daily routine from time to time and step into the magnificent world of antiquity.

Though it isn’t always a pleasant experience, I find it often gives one perspective on one’s own existence.

Thank you for your comment, Huon. In some ways, though, it’s a question of, ‘Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.’ (Apologies for missing accents.) Nebamun wants his Afterlife to be one up on his life in this world – I get the feeling that he wasn’t, perhaps, quite as important as the frescoes made out. He was, in a sense, trading up in his fantasies of what was to come.