‘For they were young, and the Thames was old,

And this is the tale that the river told.’ Rudyard Kipling

The current exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands, Secret Rivers, is about the various rivers which once flowed openly into the Thames but which nowadays are largely hidden from view. The visitor follows the stories of, in particular, the Fleet, the Walbrook and the Westbourne, all now channelled underground.

We begin in the Bronze Age; metal-working is well established and people have settled down in tribes. This is a time when rivers are thought to be mysterious places which marked the transition between two elements, land and water, and, perhaps, between life and death. We can see this in the offerings found in the Thames, particularly near where the Walbrook flowed into the Thames.

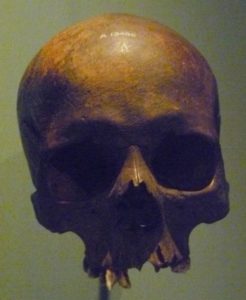

This human skull, 1260-900 BC is one of the oldest objects found in the Thames and it is thought, from its condition, to have been put there deliberately

The Roman philosopher Lucius Annæus Seneca, (c. 4 BC – 65 AD) has this advice, ‘Where a spring or river flows, there should we build altars and offer sacrifices.’

Gilded copper alloy mount, 6th-9th centuries

This small but beautiful mount, possibly made to decorate a harness, is in pristine condition. It is a high-value object and was placed in the river either as a personal offering or, as the label suggests, as an attempt to control the river by divine intervention.

Cow’s skull (The exhibition lighting is kept low to help conserve the objects.)

This animal was deliberately killed by a lethal blow which is very visible. Killing a living animal in this way is not something one does casually; it is predicated on a ritual which would have taken time and trouble to arrange, and people to witness it.

Iron quill or dagger, mid-15th-16th century

The iron quill (meaning, in this context, a sharp object) or dagger was brand new and deliberated bent to ‘kill’ it ritually and render it useless for humankind – but an acceptable offering for the gods. Its date shows that offering sacrifices continued for well over two thousand years.

Statue of a Roman river god found in the Thames

When the Romans arrived, they were used to sacred rivers and they, too, left their mark on the Thames. A large number of lead curses were found in the magnificent Roman baths at Aqua Sulis (Bath), and, recently, evidence of curses have also been discovered on the Thames riverbank.

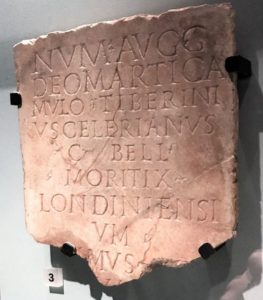

Stone tablet with curse

The stone tablet with a written curse seen above was found in the River Thames by the River Walbrook. It says: Titus Egnatius is cursed and Publius Cicerius is cursed, which sounds pretty drastic; I’d love to know what had they done to warrant such enmity. Still, whoever went to the trouble of having the stone properly carved – not a cheap job, I imagine – obviously thought that the river god would take notice and bring the villains to account.

After the Romans left in the 5th century, Londinium collapsed – the incoming Angles, Saxons and Jutes had no interest in cities and fell into ruin. But once the Normans arrived in 1066, things changed. They understood the importance of docks and city walls, and, once more, various trades developed along the Thames foreshore.

The two rivers most in evidence in the exhibition are the Walbrook which flows into the Thames inside the old city walls – which is why we see so much evidence of ritual activity there – and the notorious River Fleet which starts up in the hills of Hampstead and flows down to the Thames where it marks the boundary of the City of London’s wall.

The spoons and bowls above were bought by the prisoners for their own use

The Fleet was a wide river with two islands at its mouth. It was not long after the Norman arrival that the Fleet Prison was built on the northern island. It was a debtor’s prison and the prisoners had to buy their own food and utensils. Furthermore, you could rent yourself a private room, rather than being thrown into the filthy hold all cell; it all depended on the depth of your pocket.

Glass bottle and J Hurst’s tankard.

There exhibition also has a small but elegant glass bottle and a tankard dating from the 16th-18th centuries. The tankard has its prison owner’s name engraved on it: J Hurst and Fleet Cellar which is where he rented a room (which sounds pretty damp to me). It was not unknown for a prisoner to choose to stay in prison within ‘the Rules’, which allowed you a certain amount of freedom, rather than clearing your debt and leaving.

Wooden patterns to keep your feet clear of the dirt; the Fleet has begun its downward slide into filthy ditch

Later, the Knights Templar, a Christian military order, were granted land to the east of the Fleet to set up a mill and they filled in the channel between the southern island and the bank to increase the water flow for the mill. In so doing, the Fleet began its journey from being the River Fleet to being the notoriously unsanitary Fleet Ditch.

Stone mould for small lead alloy roundels

Other trades began to set up here, too, notably metalworking. Dozens of crucibles have been discovered in the lower Fleet valley, they were used to pour lead alloy into the stone moulds, like the one above.

Copper alloy scabbard chape

A number of ‘seconds’ have also been found of scabbard chapes (my word for the week), the metal tip at the end of a scabbard. Note the Christian cross decoration – a reminder that the Knights Templar once owned land nearby.

Wicker fish trap; fish bones bottom left

Somehow, amid all this industry, fish were still being caught in Medieval times.

Mid-12th century oak three seater toilet seat

This fitted over a cess pit behind a mixed commercial and residential building on Ludgate Hill for the use of the shopkeepers and their families. Unfortunately, by this time, the Fleet River was becoming more of a ditch full of dead dogs and cats, as well as human effluent, and less of a flowing river, which could wash away the detritus.

‘The Fleet is a secret ditch, the kingdom of typhoid, a conduit of bad air’

Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens: the Chinese House by T Bowles, 1754

The exhibition ends by moving on a couple of centuries and further upstream to where the Westbourne enters the Thames which, in 1754, provided water for the Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens. The picture above shows a delicate Chinese pavilion which looks as though it’s floating on a canal and there were, we are told, illuminations and music.

It’s a far cry from the stinking Fleet Ditch.

Child’s toy boat, bowls, and fishing tackle

What could the visitor do at Ranelagh? You could sail a toy boat – the one pictured above still has traces of paint of it. You could play a traditional game of bowls. Or you might even go fishing.

However, there were more sophisticated pleasures on offer for those who could afford it.

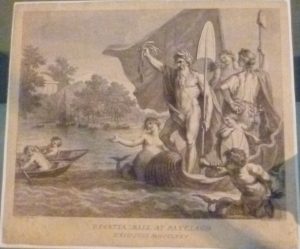

Ticket to the Regatta Ball at Ranelagh, 1775

The Regatta Ball at the Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens was obviously the ‘must do’ event of 1775. The engraved ticket shows Old Father Thames sailing down the Thames on an oyster shell, accompanied by Britannia and Abundance. A mermaid welcomes the guests and a triton blows his horn. The guests will arrive by boat, and supper will be accompanied by music and dancing.

Who could ask for more? I’d love to have been there.

The Museum of London Docklands, No 1 Warehouse, West India Quay.

200 years ago, the museum building was once a sugar warehouse, nowadays it looks at the history of London as a port dealing in trade, commerce and migration.

The Museum of London Docklands ‘Secret Rivers’ exhibition continues until 27th October and is free. It’s well worth seeing.

museumoflondon.org.uk/docklands

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Wonderful! Thanks for the tour around the various objects.

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Jan, though some of the objects are pretty revolting – who wants an ancient three seater toilet, for example? And the cow skull with a massive hole smashed in its forehead – poor thing – is gruesome, to say the least.

Really enjoyed this, thank you. Sadly, i won’t be in London during the exhibition’s duration. anne stenhouse

Thank you for your comment, Anne. It’s a museum well worth visiting at any time. It’s permanent collection is very interesting, and the location, surrounded by old warehouses along West India Quay, is pretty impressive, too.

How fascinating!

Incredible that there should be so many objects that go so far back into London’s history. I often forget about London’s Roman past and each time I am reminded I think about what it might have been like. Indeed some parts of London still look very Roman indeed thanks to the abundance of Neo-Classical architecture, so I suppose that it isn’t that hard to imagine.

I wonder what other secrets the Thames and its tributaries still hold.

Thank you for your comments, Huon, especially your perceptive point about London’s many Classical buildings. I hadn’t thought of that – and you are quite right. The next time you come to London, you must visit Museum of London Docklands and see what else they have for yourself. It goes from mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses, via Bronze Age armour to the Romans, Vikings and all the way through London’s Imperial rise and fall to today. I’m sure that more secrets will emerge from its muddy waters.