2016 is the bi-centenary of the birth of Charlotte Brontë and the National Portrait Gallery is celebrating it with a small exhibition which looks at what inspired her writing.

The Brontë Sisters by Bramwell Brontë

It opens with her brother Bramwell’s portrait of his sisters from c. 1834 when Charlotte was about eighteen. Anne, the youngest, is on the left, Emily in the middle and Charlotte on the right. The author Mrs Gaskell, who knew her well and later wrote her biography, called his portrait of Charlotte ‘a striking resemblance.’

Wellington by Robert Home, 1804

The exhibition also includes a youthful portrait of Wellington from 1804; he was not yet famous, but there is enough ‘swagger’ in the portrait, to allow us to see what attracted Charlotte. The Napoleonic Wars were over by the time she was born but they were still very much within living memory, and Wellington was a national hero as well as Charlotte’s.

Much later, in 1850, on a visit to London, Charlotte’s publisher, George Smith, took her to the Chapel Royal where she saw her now eighty-one-year old hero in the flesh: ‘he is a real grand old man’ she reported. It’s good to know that she was not disappointed.

Haworth Parsonage, photo 1857-8

Charlotte and Bramwell were very close and, from childhood, they re-enacted their own battles with Bramwell’s toy soldiers and chronicled the joint adventures and history of a fictitious Duke of Wellington and his two sons in the country of Angria. The stories were written in tiny hand-made notebooks, two of which are in the exhibition.

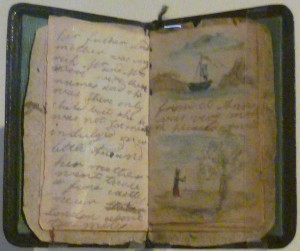

First Little Book c. 1828

What interests me about the above little book, dating from 1828 when Charlotte was twelve, is how carefully it was made. It comprises wallpaper, paper, ink, pencil, water-colour, leather, silk and cotton thread. Someone, and one suspects Charlotte, has carefully cut out the wallpaper, leather, paper and silk to the required size and sewn it together. It was obviously a labour of love.

So what did Charlotte read? The children had free access to their father’s library and he does not seem to have curtailed what they read. There was the Bible, of course; Aesop’s Fables; The Arabian Nights Entertainments: the 1001 nights; Shakespeare; classic British poets like Milton and Thomson and the author Oliver Goldsmith; and the Romantic poets, including Lord Byron. Charlotte also read the monthly Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, which stood for traditional values and the establishment. It was a wide-ranging selection – but almost entirely literature. Their father, the Rev. Patrick Brontë, was obviously not interested in the sciences.

In 1834, Charlotte wrote to her friend Ellen Nussey on What Not to Read. Of Shakespeare and Byron, she says, ‘The finest passages are always the purest, the bad are invariably revolting; you will never wish to read them twice. Omit the comedies of Shakespeare and the “Don Juan” and perhaps the “Cain” of Byron, though the latter is a magnificent poem, and read the rest fearlessly.’

Note that Charlotte was only eighteen when she wrote this, surely rather young to be pontificating about what is good and what isn’t; and she herself has obviously read the ‘revolting’ Don Juan, otherwise how would she know whether it was disgusting or not?

Whatever Charlotte’s high-minded advice to Ellen, there is no doubt that her depiction of Mr Rochester in Jane Eyre was influenced by the devilishly attractive Don Juan who has adventures galore and seduces numerous women. The Oxford Companion to English Literature comments: Byron’s ‘outspoken wit and satire are especially directed at hypocrisy in all its forms, at social and sexual conventions, and at sentimentality.’ Something in Charlotte obviously responded to this, something she wasn’t going to mention to Ellen!

Walter Scott, marble bust by Sir Francis Chantry, 1841

The exhibition also includes a marble bust of Sir Walter Scott, another of Charlotte’s heroes. In 1833, she wrote to Ellen Nussey about Varney, the villain of Scott’s Kenilworth, set in Elizabethan times and telling the tragic story of the Earl of Leicester’s wife, Amy Robsart.

‘Varney is certainly the personification of consummate villainy; and in the delineation of his dark and profoundly artful mind, Scott exhibits a wonderful knowledge of human nature, as well as a surprising skill in embodying his perceptions, so as to enables others to become participants in that knowledge.’

Mrs Gaskell, in her biography of Charlotte, perceptively observed: ‘(Charlotte) knows nothing of the world, both from her youth (she was seventeen) and her isolated position, has yet been so accustomed to hear “human nature” distrusted, as to receive the notion of intense and artful villainy without surprise.’

Charlotte’s ankle boots, probably worn with pattens

My predominant feeling about this exhibition was how well it illuminated just how precocious the young Charlotte was, both in what she read but also the sophistication and depth of her reactions to it. She knew exactly what she felt and she was not afraid to articulate it. It boded well for her future career.

I really enjoyed Celebrating Charlotte Brontë. It’s focused; the signage gives you just the right amount of background information; and it’s free. It is on until 14th August, 2016.

Photos: Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips, R.A., courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, all other photos taken by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Thank you for this post, Elizabeth. Is it true that the portrait of the sisters originally included Branwell, but that he painted himself out of it? Also, does she ever mention having read Jane Austen?

Thank you for your intelligent comments, Prem. Yes, infra-red photography has shown that the pale column between Emily and Charlotte is an erased self-portrait of Bramwell. And yes, Charlotte tried reading Jane Austen’s novels and didn’t care for them. She found them lacking in passion and with too narrow a focus. I wish I could find the quote because it’s a good one. Perhaps another visitor to my post will know. Chalk and cheese, I suppose. It’s odd though, because Charlotte thought all Walter Scott’s novels were ‘marvellous’ and Scott was a huge fan of Jane Austen!