In every film or television adaptation of Pride and Prejudice I’ve seen (and I’ve seen many) Mr Bennet comes across as a sympathetic character; a man we could like. We enjoy his irony with regard to the oleaginous Mr Collins: ‘It is happy for you that you possess the talent of flattering with delicacy. May I ask whether these pleasing attentions proceed from the impulse of the moment, or are the result of previous study?’

He finds Mr Collins ‘as absurd as he had hoped; and he listened to him with the keenest enjoyment, maintaining at the same time the most resolute composure of countenance…’ And we laugh with him.

But there is a less admirable side to Mr Bennet, one which leads to a great deal of unhappiness for his elder daughters, Jane and Elizabeth, and near disaster for the flighty Lydia who runs off with the caddish (though handsome) Wickham.

19th century reticule

At the end of Chapter 1, Jane Austen sums up Mr Bennet’s character. He was an ‘odd mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humour, reserve and caprice…’ He enjoys winding people up. He allows his wife to think that he has no intention of paying that essential courtesy call on the newly-arrived Mr Bingley, a young, unmarried man with £5000 a year, without which Mrs Bennet will not be able to introduce her attractive daughters to him. He leaves her in ignorance until he’s extracted the maximum enjoyment from her agitation before telling her that he has paid the call.

He can be unkind, too. At the Netherfield ball, his middle daughter Mary eagerly sits down at the piano and begins to sing. ‘Mary’s powers were by no means fitted for such a display; her voice was weak and her manner affected.’ Elizabeth is in agonies of embarrassment and ‘looks at her father to entreat his interference.’

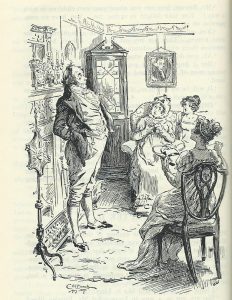

Mr Bennet tells his wife and daughters that he has called on Mr Bingley by Charles E. Brock

He picks up her hint and says, after Mary’s second song, ‘That will do extremely well, child. You have delighted us long enough. Let other young ladies have time to exhibit.’ Elizabeth must have heard the irony in his tone for she felt ‘sorry for (Mary), and sorry for her father’s speech.’ He could have done it more kindly.

But Mr Bennet is not a kind man. When Mr Bingley suddenly leaves Netherfield without having made the expected offer to Jane – and it’s obvious to Elizabeth that Jane and Bingley are very much in love – Jane is deeply upset, and Elizabeth and Mrs Bennet are full of sympathy.

Regency man

Mr Bennet’s reaction is quite different. He says to Elizabeth: ‘So, Lizzy, your sister is crossed in love, I find. I congratulate her. Next to being married, a girl likes to be crossed in love a little now and then. It is something to think of and gives her a sort of distinction among her companions.’ He suggests that Elizabeth will not want to be outdone by Jane, and recommends Wickham for the role: ‘He is a pleasant fellow, and would jilt you creditably.’

It is callous, inappropriate, and he completely ignores Jane’s very real distress.

The tone of Elizabeth’s response is interesting: ‘Thank you, sir, but a less agreeable man would satisfy me. We must not all expect Jane’s good fortune.’ On the surface, it sounds as though she is content to echo her father’s irony, but I wonder? She doesn’t call her father ‘Papa’ she calls him ‘sir’, as if distancing herself, a reaction further emphasized by her use of ‘We’ rather than ‘I’. The reader suspects that Elizabeth is hurt by her father’s reaction and that this conversation will not be passed on to Jane.

Mr Bennet in his library about to be harangued by Mrs Bennet on Elizabeth’s refusal to accept Mr Collins’ proposal, by Charles E. Brock

Then there’s the question of the Bennet girls’ education. When Lady Catherine de Bourgh cross-questions Elizabeth about her and her sisters’ education, she discovers that they grew up without a governess; and that, although Elizabeth and Mary are both musical, they never went up to London to be properly taught.

‘My mother would have had no objection, but my father hates London,’ Elizabeth tells her.

Lady Catherine might be nosy but she asks questions to which the readers, too, would like answers. ‘Why did you not all learn? You ought all to have learnt. The Miss Webbs all play, and their father has not so good an income as yours.’

Later she says: ‘No governess? How was that possible? Your mother must have been quite a slave to your education.’

These are pertinent questions; and surely it is Mr Bennet’s duty as a parent to see that his daughters have a decent education, especially considering that they might have to work for a living if they don’t find husbands. We also learn from Lady Catherine that Mr Bennet’s income could well support proper music teachers.

Of course, the reader knows that it is extremely unlikely that Mrs Bennet would have taught her daughters. So how were they educated? Possibly they went to a girls’ school in Meriton, to an establishment like Mrs Goddard’s school in Highbury in Emma, where ‘a reasonable quantity of accomplishments were sold at a reasonable price.’

The Bennet girls can all read and write and are numerate. They would have been taught to sew (Lydia pulls apart a newly-bought hat prior to redesigning it) and they had obviously had dancing lessons – they are all good dancers. We know that Mary and Elizabeth were taught the piano by somebody (even if not a London professional) and they had singing lessons.

Two Girls at School. 1817

The sisters would have learnt a modicum of British History, even if only through Miss Mangnall’s Historical and Miscellaneous Questions for the Use of Young People (1798). They know various card games. Jane, at least, can ride.

All the same, as Elizabeth says, ‘We were always encouraged to read, and had all the masters that were necessary. Those who chose to be idle certainly might.’ It is not very satisfactory.

In my view, Mr Bennet should have seen to it that none of his daughters were allowed to be idle. And he certainly failed Mary.

Mary isn’t pretty like her sisters; instead, she tries to be ‘accomplished’. But, although she is obviously intelligent, Mr Bennet doesn’t bother to teach her to think clearly. Her trite observations are allowed to stand and, doubtless, give her father some amusement, but that is, surely, not enough. He could have helped her – he is a thinking man – but he can’t be bothered.

Furthermore, a man of breeding should treat his wife with respect – even if they have very little in common. To do otherwise sets a bad example to their children. Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park, for example, always treats Lady Bertram courteously, even though she does very little apart from lying on her sofa and petting her dog, Pug. The Bertram children are expected to treat their mother with the respect which is her due.

Mr Bennet allows himself to criticize his wife in front of his children. He says of Charlotte Lucas’s engagement to Mr Collins: ‘It gratified him … to discover that Charlotte Lucas, whom he had been used to think tolerably sensible, was as foolish as his wife and more foolish than his daughter!’ And he obviously enjoys Mrs Bennet’s distress about the Lucas-Collins match – and we sympathize – after all, the Netherfield estate is entailed and it is Mr Collins who will inherit it when Mr Bennet dies not Mrs Bennet and her daughters. They will be homeless.

It is not Mr Bennet’s fault that he only has daughters, but it is his responsibility to see that his wife and children are properly provided for after his death. We are told, towards the end of the book, that he had ‘often wished that, instead of spending his whole income, he had laid by an annual sum, for the better provision of his children, and of his wife, if she should survive him.’ It was his duty to have done so, as he eventually recognizes.

Mr Bennet stunned by Lydia’s elopement by Charles E. Brock

His income is £2000 a year. If he’d saved 10% – surely not too difficult – it would have meant that the marriage settlement of £5000 would now be worth well over £9000. Luckily for Mr Bennet, Mr Darcy’s generosity enables Lydia to marry Wickham, and Mr Bennet himself ‘would be scarcely ten pounds a year the loser.’

And it is Mr Bennet’s refusal to listen to Elizabeth’s advice to forbid Lydia to accept Mrs Forster’s invitation to go to Brighton, which precipitates the final catastrophe of Lydia running off with Wickham. Elizabeth’s plea is heartfelt: she points out that she and her sisters’ social acceptance and ‘respectability in the world must be affected by the wild volatility and disdain of all constraint which mark Lydia’s character.’ And she sees Kitty, who follows her sister, being drawn in, too. ‘Vain, ignorant, idle, and absolutely uncontrolled! Oh my dear father, can you suppose it possible that they will not be censured and despised wherever they are known, and that their sisters will not be often involved in their disgrace?’

He listens, and he has an answer to her points which satisfies him, and he gives Lydia permission to go to Brighton. When push comes to shove, he always goes for the option which will cost him the least trouble.

At the end of the book, Mr Bennet has married off three of his five daughters, so money will be less tight. He could, if he so chose, start saving for Kitty, Mary and his wife’s futures. But he doesn’t, ‘he naturally returned to all his former indolence.’ Perhaps he assumes (probably correctly) that his two rich sons-in-law will make sure that his wife and unmarried daughters will be comfortable, financially. It is not an admirable trait.

There are other fathers in Jane Austen’s novels whose characters may be worthy of censure: General Tilney’s bullying, for example, or Sir Walter Elliot’s snobbery and financial fecklessness, but it is Mr Bennet’s disengagement from his daughters’ upbringing which makes him the most blameworthy, in my opinion.

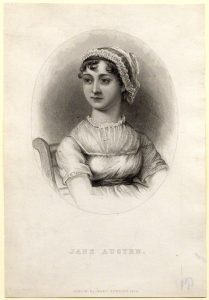

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Excellently argued piece. anne

Thank you. Anne. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I felt that too many readers blame Mrs Bennet and forget Mr Bennet’s sins of omission which, in my view, are pretty serious.

What a good piece, Elizabeth; When I first came across the Bennets, I thought Mrs B was foolish and ridiculous with her harping on about the girls catching husbands; and I loved Mr Bennet’s sardonic wit. Now I look back and feel sorry for Mrs Bennet – she was foolish, but she had wit enough to realise how important it was for her daughters to have comfortable futures with decent husbands. Mr Bennet must have known this too, but he seems to have had no sense of responsibility towards his family – he just hid away with his books, emerging now and then to make unkind remarks about his wife or younger daughters. Jane Austen is so subtle – she allows him his clever remarks, but does not applaud them.

Thank you for your kind words, Prem. While writing the post, various things came up which set me thinking. 1) Lady Catherine de Bourgh points out that Webb girls all have proper music lessons in London, in spite of their father having a smaller income than Mr Bennet’s. And 2) that, as Mrs Bennet tells Mr Collins, they can afford to pay for a good cook. It sounds to me as if Mr Bennet has money enough for his own pleasures (he’s a foodie) but he won’t bestir himself to ensure that his two musical daughters get good London teachers. He himself doesn’t like London – so it doesn’t happen.

In the book, this is only hinted at but I bet readers at the time would have picked it up. It takes modern readers a bit longer.