Jane Austen’s niece, Anna Austen Lefroy (1793-1872) was, as far as we know, her only relation who was also a novelist – though, in her case, an aspiring one. When she was nineteen, Anna asked her aunt various questions regarding her own novel Which is the Heroine? For example: does Dawlish have a decent library? Jane’s answer was that it was ‘pitiful and wretched’. What I found interesting was that Jane understood her niece’s concern to get things right. Both wrote contemporary novels and they both knew that accuracy was important.

For example, in a letter to her sister Cassandra in January 1813, Jane asks her if she ‘could discover if Northamptonshire is a country of Hedgerows.’ This seems a very minor point but she was writing Mansfield Park at the time and wanted to make sure that her depiction of the countryside around it was convincing.

Later that year, Jane learnt ‘from Sir J. Carr that there is no Government House at Gibraltar’ and that, therefore, she ‘must alter it to “the Commissioner’s’”. It gets a tiny mention by William Price when he comes to visit Fanny at Mansfield Park, but fellow writers will give Jane Austen a tick for her attention to detail. We all know how mortifying it is to be picked up on some small point we have got wrong. Readers, then as now, rightly expect authors to have done their research properly.

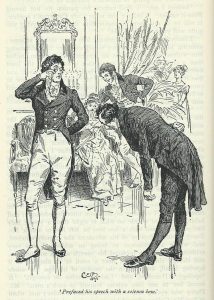

Mr Collins introduces himself to Mr Darcy

Jane then picks up on a social point in Anna’s novel: ‘I have also scratched out the Introduction between Lord P. and his Brother, and Mr Griffin. A Country Surgeon (don’t tell Mr C. Lydford) would not be introduced to Men of their rank.’ It reminded me of Elizabeth Bennet’s acute embarrassment when Mr Collins insists on introducing himself to Mr Darcy at the Netherfield Ball: ‘Elizabeth tried hard to dissuade him from such a scheme; assuring him that Mr Darcy would consider his addressing him without introduction as an impertinent freedom…’ a moment nicely captured in Charles E. Brock’s illustration above.

Later in the same letter, Jane has some further advice for Anna: ‘We (she and her sister, Cassandra) think you had better not leave England. Let the Portmans go to Ireland. But as you know nothing of the Manners there, you had better not go with them. You will be in danger of giving false representations. Stick to Bath … There you will be quite at home.’

We note that Jane Austen follows her own advice in Emma. She does not follow Colonel and Mrs Campbell and Jane Fairfax to Ireland to see the Campbell’s newly married daughter, Mrs Dixon; instead, she has Miss Fairfax insist on visiting Mrs and Miss Bates, her grandmother and aunt in Highbury, which is where we meet her. Later, the reader realizes that Miss Fairfax is doing that dangerous thing for a Regency lady – being proactive – and, when Mr Frank Churchill ‘coincidentally’ arrives, it precipitates a very tangled web of deceit indeed.

Promenade dress, 1808

We know that Jane Austen had a holiday in Lyme from her letter to her sister Cassandra in 1804. She mentions sea bathing, presumably from a bathing machine, something she really enjoyed; she attends a public ball; and walks for an hour or so on the Cobb. We have only the one letter from Lyme, but she must have taken the opportunity to note what it had to offer and used it in Persuasion many years later. (I’d have loved a scene with Anne Elliot sea-bathing!)

Jane wrote to Anna again in September 1814 with some more interesting plot advice: ‘We are not satisfied with Mrs F’s setting herself as Tenant & near Neighbour to such a Man as Sir T.H. without having some other inducement to go there. A woman, going with just two girls growing up, into a Neighbourhood where she knows nobody but one Man, of not very good character, is an awkwardness which so prudent a woman as Mrs F. would not be likely to fall into. Remember, she is very prudent, you must not let her act inconsistently.’

Reading lady from ‘The Ladies’ Pocket Magazine’

She suggests: ‘Give her a friend, & let that friend be invited to meet her at the Priory and we shall have no objection to her dining there; as she does; but otherwise a woman in her situation would hardly go there, before she had been visited by other Families.’

This refers to the custom of leaving calling cards. On moving to a new home, Mrs F. must make sure that she leaves a calling card for any lady with whom she wishes to be acquainted – presumably those introduced by her friend, or possibly, by the vicar after church on Sunday. Her calls should be returned within a week which would signify that they are happy to know her socially. But Mrs F. could not possibly dine at the Priory before this has happened.

In all of Jane Austen’s novels, her heroines need to be properly introduced to establish their social credentials. Emma’s friendship with Harriet Smith is important in giving Harriet an entrée into Highbury society – something which Harriet, a mere parlour border with a dubious pedigree, could never have done on her own.

From ‘The Ladies Pocket Magazine’

Anne Elliot is entirely dependent on the Musgroves to re-introduce her to Captain Wentworth; to include her in the outing to Lyme; and on Lady Russell to take her to Bath. Lady Russell can travel where she likes, but then, she’s the widow of a well-to-do knight and has her own private carriage. Unmarried ladies, like Anne, have very little opportunity to be proactive.

Lastly, Jane’s other piece of advice to her niece is well-known but worth repeating: You are now collecting your people delightfully, getting them exactly into such a spot as is the delight of my life; 3 or 4 Families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on… I hope when you have written a great deal more you will be equal to scratching out some of the past. The scene with Mrs Mellish, I should condemn; it is prosy & nothing to the purpose.’

Frontispiece from ‘Correspondence between a Mother and Daughter’ by Ann Taylor, 1817

How many of us write scenes which we realize, in the cold light of morning, are ‘prosy & nothing to the purpose’. Another earlier comment is: ‘till the heroine grows up, the fun must be imperfect.’ This is a trifle odd, considering that she wrote this in 1814, the year Mansfield Park came out. On this occasion, she does not follow her own advice; Mansfield Park is the only novel where Jane Austen shows us her heroine, Fanny, as a child.

Sadly, Anna did not fulfil her literary ambitions – apart from a couple of short stories and a novella published in the 1840s. A few months after this exchange of letters with her aunt, she married the Reverend Benjamin Lefroy. He died in 1829 leaving her with seven children and very little money. It may explain why she abandoned Which is the Heroine? and later burnt it.

But we owe her a debt of gratitude for giving us a glimpse into how Jane Austen constructed her novels and what she thought was important.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...