This post is about two Arts and Crafts oak chairs with Walter Crane tiles, bought for ten shillings (50p), with an intriguing story to tell. My mother, who loved auctions, got them from Mr Little’s Salerooms in Barnard Castle, an attractive upper Teesdale market town.

The first History chair

They were, she explained, hall chairs, you weren’t meant to sit on them. In fact, they are excruciatingly uncomfortable, not to mention unsafe. I wouldn’t trust the front right leg of one of them (see photo above) and the other creaks ominously. But I like them, and I’m a fan of Walter Crane (1845-1915), an eminent artist who collaborated with William Morris. The tiles say a lot about late Victorian England and what people thought was important about English history. (And it’s definitely English history, as opposed to British.)

Julius Caesar tile by Walter Crane

Each chair has two tiles. The earliest, historically speaking (54 B.C.), is Julius Caesar stepping proudly down from a Roman ship – looking amazingly unruffled, considering that his fleet has only just survived a ferocious storm. Behind him, a standard bearer holds the Roman standard saying SPQR, (Senatus Populusque Romanus: The Senate and the People of Rome) the symbol of the Roman republic and its democratic rule by all its citizens – at least, in theory, and providing they were male, and free.

The Victorians approved of the Romans; they saw the British Empire as inheriting the Roman Imperial mantle. From the 19th century point of view, the Romans came to civilize the barbarian Britons. What is conveniently glossed over is that the Romans, having, with difficulty, defeated Cassivellaunus, the powerful king of the Catuvellani tribe, took a few hostages, demanded an annual tribute, and left, not to return for ninety years. So not much imperial authority in evidence there!

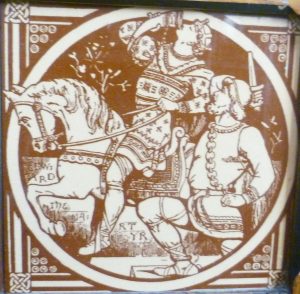

St Augustine preaching to King Ethelbert by Walter Crane

The second tile shows St Augustine preaching Christianity to a scowling King Ethelbert of Kent and his approving Frankish wife, Bertha in 597 A.D. Pope Gregory the Great had sent Augustine to convert the English to Christianity (though, in fact, a number of Christians had already been converted by Irish priests in Roman times). Ethelbert’s influence spread as far north as the Humber, so he was a fish Pope Gregory wanted to land; and he was after control as much as conversion.

King Ethelbert hedged his bets and continued to worship Thor and Odin as well as allowing Augustine to preach Christianity and build churches. There were no forced conversions and he himself only converted on his deathbed.

The second History chair

Spreading Christianity was also something the Victorians approved of; it gave the British Empire a sort of moral legitimacy in their eyes. So we can see that, in theory, the tiles commemorate important historical episodes; but they are also suggesting, subliminally perhaps, that English history has been guided by Divine approval.

King Edward the Martyr by Walter Crane

The second chair continues the English history lessons chronologically. The next tile shows the death of the Anglo-Saxon king, Edward the Martyr, who became king when he was fifteen. His claim to the throne was disputed by his step-mother, on behalf of her son, Ethelred, who was only ten (Edward may have been illegitimate). The succession was decided in Ethelred’s favour. Edward went to Corfe to visit his half-brother and step-mother, where he was dragged from his horse and murdered.

The tile shows Edward, head thrown back, draining the drinking horn he has been offered in welcome, while a dastardly retainer is about to plunge a dagger into his back. When Ethelred grew up, he enthusiastically promoted his dead brother as a saint and martyr, ‘who, drenched with his own blood, the Lord has seen fit to magnify in our time through many miracles.’ Having a brother as a saint undoubtedly promoted Ethelred’s own status – and he needed it; he was to become notorious in English history as ‘Ethelred the Unready.’

A tile showing Edward the Martyr is a curious choice to modern eyes but it confirms, I think, the importance to Victorians of cementing the Christian faith with royal, if somewhat dubious, martyr’s blood, if necessary.

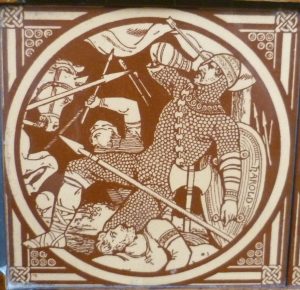

The Death of Harold by Walter Crane

The last tile shows a scene which is more familiar to us; the death of King Harold in 1066. Crane shows him clad in chain mail, falling to the ground, his hand clutching the arrow in his right eye. Nowadays, we are more ambivalent about the Norman Conquest than the Victorians were. For them it was a Good Thing, and Harold’s perjury in swearing an oath on holy relics to support William becoming king when Edward the Confessor died, and then reneging, proved that he was a villain. Being killed by an arrow through your eye was a sign that you were a perjurer.

Again, the tile has a Christian lesson: Harold died a perjurer’s death and William was rightful king of England. And, by extension, the English, and later, the British, ruled ‘by Heaven’s command.’

I’m not sure what tiles I’d go for, if I had the choice. I’d have to think carefully about what line I wanted to take. If I wanted to emphasize Britain’s democracy, for example, I might start with King John signing Magna Carta at Runnymede. And I’d certainly want to include Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish hisdtory.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Great post Elizabeth – interesting how the episodes are selected, as you say. Fabulous tiles – with the figures reaching beyond their frames to emphasise their importance. It’s hard to mistake the message, even if you aren’t sure of who the figures are.

If you’re looking for more uncomfortable chairs, have you visited the metal chairs erected on Runnymede? They are a recent attempt to answer your question of what a modern history-lesson chair might depict.

Thank you for bringing the Runnymede chairs to my attention, John. I must check them out. I, too, like the way a hand, a foot, or even a horse’s ear protrude out from the circles which frame Walter Crane’s tiles. It makes St Augustine’s gesture even more meaningful; and Julius Caesar looks as though he’s about to leap out of the boat.

Fascinating. Love the reference to 1066 and All That. Must read it again. It’s so interesting how generations skew history to suit themselves, like our modern day spin doctors. Wonderful chairs, by the way.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. I’m glad you enjoyed my ‘1066 and All That’ reference. I was very tempted to quote it on Ethelred the Unready as being a ‘Weak King’, never ready to fight when the Danes were. I’m pleased to like my chairs. I love them but I have to say that, as chairs, they are pretty useless!

This is a really interesting analysis. History, as shaped by the spin-doctors.

Thank you for your intelligent comment, Jan. I hadn’t thought of it like that, and you are right. It’s just a different spin from what we are used to in the 21st century.