Mary Crawford’s harp is more than just a fashionable early 19th century musical instrument, it has a number of important jobs to do in the unfolding of the Mansfield Park plot, not least in allowing the readers to see Mary’s character for themselves.

Young Lady Playing the Harp by James Northcote, 1816

The harp has come by carrier from London to Northampton, and Mary is astonished that no farmer will hire out his cart to bring it to Mansfield Park parsonage, where she is staying with her sister, Mrs Grant. ‘I thought that it would only be ask and have… Guess my surprise when I found that I had been asking the most unreasonable, the most impossible thing in the world!’

Edmund explains that farmers are ‘in the middle of a very late hay harvest’ but it is obvious that Mary doesn’t understand the importance of this. She thinks that her convenience should come first and that ‘everything is to be got with money.’

Frost Fair on the Thames, aquatint, February 1814

Jane Austen completed Mansfield Park in 1814, a year which had had one of the coldest winters on record; for most of January and February, the temperature in London was well below freezing. Even by midsummer’s day, icy patches still lingered in the countryside and 1814 became known as ‘the year without a summer’. The rising cost of fuel led to great hardship amongst the poor and a late and patchy harvest meant that the cost of bread rose. Starvation beckoned. Edmund is well aware of this. Mary chooses to ignore it. Jane Austen’s original readers would have chalked up Mary’s self-centredness.

This little episode reminds us that Jane Austen was a contemporary writer, not an historical one. She wrote about the here and now of her time and her readers would have picked up her references.

However, Mary’s brother Henry has offered to collect the harp in his barouche. ‘Will it not be honourably conveyed?’ asks Mary, brightly. Edmund ignores this as he will ignore other clues about Mary’s character. Instead, he says that the harp is his favourite instrument and begs to be allowed to hear her play.

Lovers: The Ladies Pocket Magazine

At this stage, Mary is more interested in Tom, Edmund’s brother, and heir to the baronetcy. But Tom has gone off to the races. Mary tries to lure him back. ‘Now, Mr Bertram, if you write to your brother, I entreat you to tell him that my harp is come, he heard so much of my misery without it… I shall prepare my most plaintive airs against his return, in compassion to his feelings, as I know his horse will lose.’ Does Edmund recognize her little game? If he does, it’s unconscious. He fails to take the hint and states that he has no occasion to write to his brother. In affairs of the heart, Edmund is worryingly naïve.

But we learn something else, too; that Mary sees her skill with the harp as part of her sexual armoury. An elegant woman, sitting at an elegant instrument, allowing her bare arms to show (sleeves would risk getting caught in the strings) as she plays, has a very seductive instrument in her hands. And by Chapter 7, she’s in a fair way to capturing Edmund’s heart with its aid.

Lady with a Harp, Eliza Ridgely by Thomas Sully, 1818

Once her harp is in the parsonage, it has to stay put and, if Edmund wants to hear her play, he must visit her there. As Jane Austen put it: ‘A young woman, pretty, lively, with a harp as elegant as herself …. was enough to catch any man’s heart. The season, the scene, the air, were all favourable to tenderness and sentiment. Mrs Grant and her tambour (embroidery) frame were not without their use (Mary needs a chaperone) it was all in harmony.

Mary knows exactly how useful the harp is for a young woman who needs to be chaperoned when with a young man. It provides the perfect excuse, and every morning’s playing ‘secured an invitation for the next.’ The spider has the perfect cobweb to lure her prey.

It is interesting that Edmund’s daily visits to the parsonage go unnoticed by the rest of his family – apart from Fanny. But he’s a man – he doesn’t need to be chaperoned.

Fanny can’t go uninvited to the parsonage, and we can see the skill with which Jane Austen keeps us – and Fanny – on tenterhooks. Part of Fanny wants to hear the harp for herself, and another part of her, surely, wants to keep an eye on what is going on between Mary and Edmund – however painful it might be.

Two Regency Ladies at the Pianoforte

It is not until Chapter 22, that Fanny is at last invited to the parsonage. Edmund is away from Mansfield being ordained, and Maria, now married to Mr Rushworth is on her honeymoon, accompanied by Julia – an odd custom, but one which was common at the time. If Mary wants some young company, Fanny is the only person available.

Fanny expresses a wish to hear the harp and Mary is very obliging and laps up Fanny’s wonder and admiration at her playing. She insists that Fanny stays: ‘I want to play something more to you – a very pretty piece – and your cousin Edmund’s prime favourite. You must stay and hear your cousin’s favourite.’ I can’t help wondering if Mary has, perhaps unconsciously, picked up Fanny’s interest in Edmund and wants to demonstrate her own hold over him by a bit of flaunting.

Young Lady at the Pianoforte, 1808

Poor Fanny. Part of her is pleased to hear Edmund’s favourite air but another part of her is desperate to get away from the parsonage, and Mary. Instead, she finds herself going over every few days. ‘It seemed a kind of fascination; she could not be easy without going, and yet it was without loving her, without ever thinking like her, without any sense of obligation for being sought after now when nobody else was to be had; and deriving no higher pleasure from her conversation than occasional amusement; and that often at the expense of her judgement…’ This is deep stuff and we realize that Fanny’s responses to Mary show a growing confidence in her own judgement of Mary’s character, even if, emotionally, she, too, is trapped by Mary’s web.

But Fanny is learning fast. She successfully fends off Mary’s probes about what Edmund thinks of the Miss Owens with whose family he is staying after his ordination. Mary also tries to extract an assurance from Fanny that Edmund will miss her once she returns to London, as she soon must, but Fanny refuses to oblige.

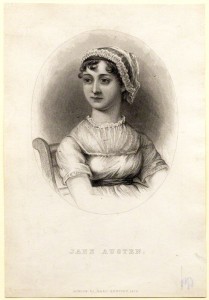

Jane Austen, after Cassandra Austen, stipple engraving, 1870, National Portrait Gallery

The harp has now done its work of enticing Edmund and we hear no more of it. From now on it will be Mary’s own behaviour which determines whether Edmund proposes to her or not. As for Fanny, the harp has also played its part in her own development. Each time she hears it played at the parsonage, she returns more and more convinced of Mary’s lack of a moral compass.

It may seem that Mary’s harp has a very minor role in Mansfield Park, but, imagine the plot without it, and one soon realizes that its role is pivotal. It is more than just a harp, it is a means by which Mary’s character – and Edmund’s gullibility – can be demonstrated to discerning readers; and, indirectly, it provides Fanny with an opportunity to grow in understanding.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

This is a very interesting post and I agree with all of it. I have also always thought the mere fact of Mary having a harp at all emphasises how completeley from another world she is. The point about it being a lure to her ‘home ground’ at the parsonage is one I don’t think I’d consciously picked up on.

(Edmund’s naivety in affairs of the heart – while charming in a probationary vicar – irritates me SO MUCH)

Thank you for your comments, Jan, which made me smile. I agree about Edmund. He’s not my favourite Austen hero; I’d like him more if he had a few faults. On the other hand, he’s the only one who notices that poor little Fanny is desperately unhappy when she first arrives at Mansfield Park, and does something about it. He’s kind – a virtue I appreciate more and more the older I get. He may be naïve but he knows how to love, and that’s important.

Oh yes, I love Edmund for his kindness and his wrestles-with-concience. I just wish he’d wake up so much earlier.

I agree. His real problem is that he was born two hundred years ago into an ultra respectable baronet’s family. Fast forward him two hundred years and he’d wise up pretty fast!

Insightful and interesting. Thank you.

Thank you, Catherine. Much appreciated.

What an insight! I love the interplay of the harp you’ve seen here. I’ve read Mansfield Park so little that it doesn’t ring a bell with me, but you’ve actually inspired me to have another look at it. I didn’t like it when I read it, so have not repeated the experiment. But from a more mature age, I might well find more to like about it.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. I read a comment on the internet from a woman who’d always loved Mansfield Park because, as a small and, she felt, unwanted child, she’d identified 100% with the timid and frightened Fanny preferring to stay unnoticed. It’s a very un-21st century stance but I could understand where she was coming from. Mansfield Park is about the damage that people with an unreliable moral compass can do; and, in order to appreciate the book, you need to find a way to be on Fanny’s side – again, not easy nowadays.

But, if you can do that, it’s a very rewarding book. I’d be interested to know how you got on.

An interesting post. Mansfield Park is well down the list of my favourite Austen novels, but I’m inspired to give it another go.

I’m thrilled that my post has inspired you to give Mansfield Park another go, April. It’s the only Austen novel where the heroine is a child when we meet her – and one, moreover, from a very disadvantaged background. She’s an outsider, and that makes her particularly interesting, I think. She never, not even as a child, rates Maria, Julia and Mrs Norris as they rate themselves.

I never had a problem with Fanny and have always had a soft spot for her, since she reveals the Hampshire woman in Jane Austen. It was a bit of shock, though, to discover just how different Fanny’s home life was from that at Mansfield Park. It was also very difficult to believe that Mrs Price was sister to Lady Bertram and Mrs Norris, since her circumstances are so different. A real warning about not marrying beneath oneself.

It is Edmund who is the weakness in the novel. It’s all very well that he is the only one who is kind to Fanny, but he takes forever to appreciate her and he gives unworldliness a bad name.

I fear you’re probably right about Edmund, April. I agree that his virtuous behaviour can be very trying. All I can say in his defence is that he’s still young, about twenty-four, by the end of the book. You may not agree, of course, but, in my experience, young men of twenty-four are often still wet behind the ears. They think they are grown up but, actually, there’s often an awful lot they don’t know. By about twenty-six, though, all has changed and they are fully adult.