In the 19th century, screens were very popular and many well-to-do day homes had one. They comprised three wooden frames hinged together, with hessian stretched across each frame and painted to create a base for illustrations. The owners would decorate the screen themselves. They could buy a whole range of painted decorations – often flowers, birds or animals – and customize the screen to suit their own tastes. Looking at the oval photographs of Princess Beatrice (Queen Victoria’s youngest child) and Prince Henry of Battenburg which probably celebrates their wedding in 1886, I’m guessing that my screen dates from the late 1880s, and I suspect that the original owner was female, romantic and about thirteen. I’ve named her Muriel after my great-grandmother.

One of the pictures is interestingly misleading.

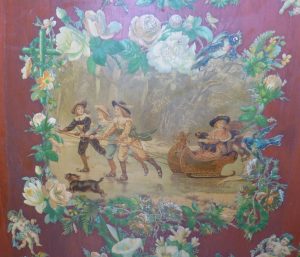

Three boys pulling girl in sleigh on the ice

What interests me about this picture is that it’s not quite what it appears. At first glance, it looks like we are in the 17th century. There is a wood with a frozen lake in the foreground. Three young Cavaliers are pulling an ornate gold sleigh with a pretty little girl and her dog sitting in it across the ice. The prow is carved with a gilded cupid shooting an arrow at one of the boys – perhaps the one who is glancing over his shoulder at the girl.

Why the interest in the 17th century? Captain Marryatt’s The Children of the New Forest (1847) was a popular adventure story about four Cavalier children: Edward, Humphrey, Alice and Edith Beverley, whose home was destroyed by dastardly Roundheads. They fled to the New Forest where an ancient forester taught them forest ways and how to be self-sufficient. It swiftly became a children’s classic and I’m sure that Muriel would have read it. Could this best-seller be the source for the screen picture?

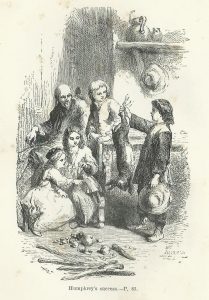

Sir John Gilbert’s illustration for ‘The Children of the New Forest’: Humphrey traps a hare for dinner

I think not. One feels that the three boys would be perfectly useless at trapping a hare, as Humphrey does. I think the screen picture is more about how Victorians viewed Cavaliers: ‘Right and Wromantic?’. There’s no hint of any struggle between a king who believed in Divine Right and a Parliament who believed they had a right to have a say in how the country was governed.

To put it crudely: it’s sentimental pap – but pretty. (Muriel has edged it with entwining dog roses and birds.) The boys wear velvet suits with knee breeches and lace collars. Each boy has a coloured sash around his waist whose ends fly in the wind. Their brimmed hats sport a jaunty feather and, naturally, they have long flowing hair. The girl, too, has a brimmed hat and wears a rose-coloured cape edged with white fur.

But then I thought: am I barking up the wrong tree? Perhaps the screen picture isn’t meant to be 17th century at all. Could it represent the influence of Frances Hodgson-Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886) on boys’ fashion?

The Little Lord Fauntleroy suit, 1886

The illustration is taken from The Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century by C. W. and P. Cunnington. The suit ‘comprised a velvet tunic, extremely short-skirted, tight knickerbockers with a wide sash round the waist with hanging ends on one side. At the neck was a white lace collar falling over the shoulders. The hair was long.’

Initially, it was a party suit but, soon, doting mothers in both America and Britain made their sons wear it every day. Not unnaturally, many boys absolutely hated it; Frances Hodgson-Burnett’s son, Vivian, for one. He was the unwilling model for the illustrations of the book’s eponymous hero. The poor lad found it ‘a lifelong embarrassment’. Even though his mother relented and let him have his hair cut, he still had to wear the suit.

I think you will agree that the three skating boys are more Little Lord Fauntleroy, than 17th century children. And that Muriel obviously has a taste for the Little Lord Fauntleroy look. Perhaps she also enjoys imagining herself with three boys in thrall – literally – as they pull her across the ice. I wonder if she grew up to write romantic novels?

A very Happy Christmas to you all.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth Hawksley, Victorian screen, 19th century children’s costume, Little Lord Fauntleroy

Please share this page...

Completely agree with you. It looks much more like Little Lord Fauntleroy than anything else. I didn’t know about her son being the model, etc. Oh, Lord, that poor boy! How embarrassing for him! You’d never get away with that sort of sickly sentimentality in a children’s story today.

Friends of my father’s sent their son to a school where the uniform was crimson knickerbockers! I always thought the poor boy must have loathed it, along with his mates. Ghastly in this day and age.

Glad you enjoyed it, Elizabeth. The American writer, Stephen Crane, felt so sorry for two boys who hated their long hair that he gave them money to go to a barber’s to have their curls cut off. One boy’s mother had hysterics, the other fainted! Compton Mackenzie, author of ‘Whiskey Galore’ was another victim, as was A. A. Milne!