Recently, I re-visited Westminster Abbey; I hadn’t been there for years – the last time I went, there were few visitors and you were allowed to go wherever you wanted. What I remembered was the soaring Gothic architecture and the wonderful fan vaulting of the ceiling. I loved St Edward’s shrine and the various chapels of the early English kings and queens; and I was able to wander round and enjoy the peaceful atmosphere of 800 years of prayer, largely uninterrupted.

St Edward’s the Confessor’s shrine.

My visit this time was a very different experience. I arrived early but the abbey was already full. It wasn’t exactly noisy, for everyone had audio guides, but that aura of peace had disappeared. It was impossible to stand back and look at something properly because people kept interrupting my view. And in Poets’ Corner, I couldn’t find the stone commemorating the poet I was looking for because someone was standing on it.

The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior

Fortunately, the tomb of the unknown warrior is still as moving as it always was. There’s something about the simplicity of the words engraved on it which, unlike many of the other funeral monuments in the abbey, deliberately emphasise the man’s anonymity. Neither his rank nor his status is important; he is, as we all are, just a human being, and, therefore, he can represent Everyman.

BENEATH THIS STONE RESTS THE BODY

OF A BRITISH WARRIOR

UNKNOWN BY NAME OR RANK

BROUGHT FROM FRANCE TO LIE AMONG

THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS OF THE LAND

AND BURIED HERE ON ARMISTICE DAY

11 NOV: 1920, IN THE PRESENCE OF

HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE V

HIS MINISTERS OF STATE

THE CHIEFS OF HIS FORCES

AND A VAST CONCOURSE OF THE NATION

This visit, though, it wasn’t the architecture that caught my eye, it was the huge number of grandiose marble monuments thrusting themselves forward along the aisles and transepts and down the nave. No modesty for them! Here putti and angels recline on clouds; the goddess Minerva looks up at a dead hero; four armoured knights kneel around a tomb; Classical muses mourn (whatever are they doing in an abbey?); and there are yards of marble drapery everywhere. It is ostentatious to a degree.

Monument to Joseph Gascoigne and Lady Elizabeth Nightingale by L-F Roubiliac in St Michael’s Chapel, 1761

Having said that, I make an exception for the above monument which has to be one of the most dramatic in the Abbey; The skeletal figure of Death is aiming a lance at Lady Elizabeth which her husband gallantly tries to intercept. It might well be described as way over the top but its sheer chutzpah redeems it. I like it.

However, in general, I agree with Nikolaus Pevsner’s comment: ‘It is sheer perversity to deny that the monuments lessen the impact of the architecture.’ Not only is the abbey’s architecture dwarfed by the volume and size of the marble figures but, frequently, the background of the sculptures crawls up the wall and cuts out the light from the windows.

The high altar

The other thing which struck me was how obscure most of the subjects of all this ostentatious mourning are to a 21st century viewer. Doubtless the various earls and dukes were important in their day, but now, I couldn’t help feeling, they were surely superfluous to requirements. And the small, obscure memorial to Jane Austen, tucked away in Poet’s Corner, only emphasizes the topsy-turvy values of the majority of the abbey’s memorials, where status and size is of overarching importance.

However, this visit, what I’d really come to see was the new Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries, and I was glad to escape from the bustle of the ground floor and take the lift up seven storeys to the 13th century Triforium. And I have to say these new galleries are wonderful.

Windows in the Triforium. In the centre are the maquettes for the statues of the modern Christian Martyrs from the Abbey West Front.

There is an atmosphere of peace and calm here and it isn’t over-crowded. The new galleries’ space is beautifully designed to allow in natural light but, at the same time, shield the often delicate objects from harmful direct sunlight.

There is a stupendous view looking down a vertiginous 52 feet to the sanctuary, quire and the nave. I am a Cosmati fan (I discovered the Cosmati brothers’ work when I was in Italy) and I loved being able to look down on part of the Cosmati floor and the dramatic black and white lozenge tiles in the quire from above.

Detail of the Cosmati pavement.

I particularly wanted to see the funeral effigies, mainly of English kings and queens, from the early 14th century to the seventeenth. Originally, the effigy of the deceased monarch, wearing his (or her) clothes, with perhaps his sword or helmet, was placed on top of the coffin and carried in the funeral procession.

Wooden effigy of Catherine de Valois, 1437, wife of Henry V

The funeral effigy of Catherine de Valois, queen of Henry V, dating from 1437, is one of the earliest It is made of painted wood. Originally, it would have been dressed in her clothes, and given a wig and possibly a crown. This is the nearest we can get to what she looked like: small, and with a thin face.

Interestingly, the gallery also has some of the funeral achievements belonging to her husband, Henry V: his helmet, and the saddle he may have used at the battle of Agincourt in 1415. Usually, the pieces of armour would then be hung up above their owner’s tomb, as the Black Prince’s helmet and chain mail used to hang over his tomb in Canterbury Cathedral.

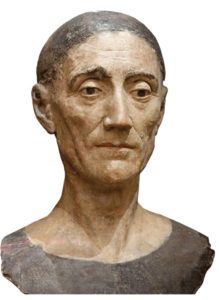

Effigy of Henry VII by Pietro Torrigiano

The effigy which is undoubtedly the most life-like is that of King Henry VII, dating from 1509, which may be modelled on Henry’s death mask. The Florentine sculptor, Pietro Torrigiano, was invited to England to make the magnificent tomb of Henry VII and his queen, Elizabeth of York. The effigy is obviously of the same man.

Effigies of Catherine, Duchess of Buckingham and her son

Two of the most interesting effigies are those of Catherine Sheffield, Duchess of Buckingham who was the illegitimate daughter of King James II, and thus half-sister to Queen Mary II and Queen Anne; and her three-year-old son, Robert, dating from 1735. The wax features of both mother and child are particularly fine. Their clothes are thought to be their own; Catherine also wears her undergarments as well as her brocaded silk underskirt; and Robert’s silk coat and velvet robe have little slits at the back for leading reins, a poignant reminder of how young he was.

Wax effigy of Lord Nelson

There are also effigies of national heroes, such as Lord Nelson, and the effigy above was made by Catherine Andras, a well-known wax modeller. He, too, wears some of his own clothes, such as his coat. Nelson’s mistress, Emma Hamilton, declared it to be an excellent likeness – or it would be ‘if a certain lock of hair was disposed in the way his lordship always wore it.’ She was allowed to make the alteration. His hat (genuine) is displayed beside him.

Replicas of the regalia

I was also interested to see the replicas of all the regalia used at the coronation. They were made for the coronation of King George VI, to be used for rehearsals, and then kept for display. They comprise a lot of objects, including two crowns – St Edward’s crown which has 444 semi-precious stones in a solid gold frame and is extremely heavy which is worn only for the actual crowning; the other crown, the Imperial State Crown is lighter, and it worn for the procession out of the abbey. Naturally, the stones etc. in the replicas are not real, but the weight is the same as the real objects. Then there is the sceptre, the orb and ampulla (small containers for the holy oil), the staff, spurs and armills (sort of bracelets). Some of these were worn or carried by nobles to represent kingship and royal dignity.

I can quite understand that a coronation needs a rehearsal with proper replica regalia so that the new monarch knows what to hold in which hand and how heavy or unwieldy it is. It wouldn’t do to drop the orb.

I particularly liked the sense of space in the Triforium galleries. The objects were well chosen and well-displayed. For example, there were some interesting books and documents which, alas, don’t photograph well for a blog as the detail is too small.

I can see that Westminster Abbey needs all the income it can get from visitors; a building of that age must be always be in need of expensive maintenance, but, for me, alas, the visit to the ground floor of the abbey was not a particularly pleasurable experience. However, the visit to the Diamond Jubilee Galleries was well worth the extra cost and I heartily recommend it.

Photos: Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

This is fascinating. I have been thinking about visiting those galleries since they opened. I really must go now. Thank you for the added incentive I needed.

I’m sure you’ll enjoy them, Janet. There’s also a splendid effigy of Charles II – a man who rather floats my boat. I thought I wouldn’t mention that in the post – decorum and all that – but, on reflection I doubt very much that he’d have objected to some female admiration, even 350 years after his death.

I like the sound of the effigies. So interesting to see how they really looked – or as close as you can come. Nelson doesn’t look much like his portraits, I thought, but sculpture is usually more lifelike than a flat painting. I was expecting it to be a bit macabre from what you said, but in fact it’s quite acceptable and interesting.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. The effigies aren’t a bit macabre; they are, as they are meant to be, not just life-like but as they were at their best. There’s none of the memento mori stuff with skeletal cadavers, for example.

I also liked the Coronation Copes on display. Traditionally, the new monarch presents the clergy taking the coronation with a gift of new fabric for the copes. In 1953, the Queen had blue and gold floral silk copes made for her Coronation. However, the Dean chose instead to wear the scarlet cope with gold stars and flowers made for the Coronation of Charles II. It’s a splendid garment but it made him look like Father Christmas!

Thank you for the photographs. I agree with you about the shuffling crowds. It is hard to remember that this is a religious building. Going to a service there is highly recommended if you want to regain a better sense of the real purpose of the abbey. The Triforium Gallery is a wonderful addition and very well laid out and lit. I was pleased to see memorials to Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear in Poets’ Corner. CS Lewis is there too. So obviously humorists and fantasists are permitted. But P G Wodehouse’s stone is still in the pipeline (I asked!) The lovely stone commemorating the War Poets of 1914-18 was new since my last visit decades ago and was a real delight.

Thank you for your comment, Pauline. I agree with you about the First World War poets’ commemorative stone. The script had an elegant simplicity that was absolutely right, I thought. And I liked the way that all the war poets were remembered, not just those who were killed; it acknowledged that Armistice Day didn’t mean that everything suddenly went back to normal. Many of the war poets suffered severe breakdowns after the war.

When my mother and I visited the Abbey, probably back in the 60s, we got talking to a porter who drew us into his cubby-hole and showed us what was reputed to be a door covered in human skin. You could still see bits sticking out from underneath some of the boards.

Gosh, Jane, how revolting – but fascinating. It’s certainly a unique selling point!Thank you for sharing this – I’m sure my readers will enjoy this gruesome titbit!

Just joining in the conversation here, hope you don’t mind. I seem to remember reading some time ago that things like that happened when someone was ‘skinned alive’ and that the practice was then to cover a door with it. Don’t know how that true that was!

Ugh! But in an Abbey? If four reputable knights could hack down Thomas Becket in front of the altar in Canterbury Cathedral, others would probably be capable of flaying a man and covering a door with his skin. There are certainly enough swords and helmets belonging to various kings up in the Triforium to show that they were a bloodthirsty lot.

I was expecting everyone to tell me it was a con, which it probably was. I’ve never heard it mentioned in connection with Westminster Abbey since. On the other hand perhaps they don’t want tourists flocking to see it!

I’ve googled this, Jane. And you are quite right. The door, which dates back to Edward the Confessor’s time, is the oldest door in Britain. It was originally covered in either animal – or human – skin. And here the legends begin. Some say it was covered with a Viking skin; others that it was animal hide – a sort of early insulation?

Thank you for bringing it to my notice. It’s certainly livened up the blog traffic!

Well fancy that! It certainly was a very ancient-looking door.

And I’ve just found this on Wikipedia! ‘In 1303, the Treasury of Westminster Abbey was robbed while holding a large sum of money belonging to King Edward I. After arrest and interrogation of 48 monks, three of them, including the subprior and sacrist, were found guilty of the robbery and flayed. Their skin was attached to three doors as a warning against robbers of Church and State.[4] The Copford church in Essex, England, may have been found to have human skin attached to a door.

I think I may have read about the procedure in one of Ken Follett’s medieval abbey books but I can’t remember which one.

Oh my God! Extraordinary how barbaric people thought it was okay to be.

I’m flabbergasted! You would think is would be one of the Abbey’s USPs – but plainly not.

Once again many thanks for this post. You always take us to some fascinating places, Elizabeth! Places that I am now unlikely to see. I remember going to Westminster Abbey on my first trip to London back in the mid 1950s when it would probably have been as quiet as you remember it. Still a very moving experience.

Thank you for your kind words, Anne. Have a look at Jane Gordon-Summing’s comment. Perhaps the Abbey is not such a quiet place, after all!