My late 19th century copy of Manners and Rules of Good Society by ‘A Member of the Aristocracy’ deals with everything a novelist or reader could possibly want to know about how Society operated and, as far as I can tell, the same rules applied in the Regency period. This week, I want to look at the knotty question of how one introduces somebody to someone else with regard to Jane Austen’s novels, or, indeed, any Historical novel set before the First World War.

‘Manners and Rules of Good Society’ by a Member of the Aristocracy. My copy is an 18th edition which dates from 1892

A proper introduction to a young man was vital to a heroine’s social acceptability and the basic rules are simple: a gentleman is always introduced to the lady, not the other way about, no matter what his rank. This allows the young lady to say, ‘Mama would not wish me to be introduced to Lord Wildblood’, thus avoiding an acquaintance which might damage her reputation.

For example, in 1814, Lord Byron sought an introduction to Lady Charlotte Leverson-Gower from a mutual friend – and his reputation as a rake who was, as Lady Caroline Lamb put it, ‘Mad, bad and dangerous to know’, was well known. Fortunately, the friend was eager to oblige. Lord Byron wrote in his diary, ‘I stopped him and said he had better ask her first, and in the mean time, to give her entire option, I walked away to another part of the room.’ Byron’s good manners paid off; Lady Charlotte agreed to the introduction – though one does wonder what her Mama had to say to her afterwards.

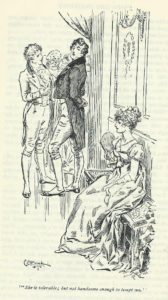

Elizabeth Bennet in ‘Pride and Prejudice’ is in a humiliating position at the Meryton Assembly. The illustrator, Charles E. Brock, shows her looking fixedly ahead, her fan raised to hide her face.

However, this rule could cause problems for young ladies. The Season (between May and June) was her opportunity to find a husband and there were not too many years to do it in – she would be considered on the shelf by twenty-five. She couldn’t introduce herself to an unattached gentleman, so she needed somebody to introduce her, which meant that the gentleman concerned would then ask her to dance. We see this at the Meryton Assembly in Pride and Prejudice where Bingley offers to get Darcy an introduction to Elizabeth: ‘Do let me ask my partner (Jane, Elizabeth’s sister) to introduce you’. Note Bingley’s assumption that Elizabeth would not refuse.

Darcy declines to be introduced: ‘She is tolerable but not handsome enough to tempt me, and I am in no humour at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men.’ We see at once how highly Darcy rates himself. If he condescends to ask Elizabeth to dance, it would raise her consequence in the eyes of other men – men who have already chosen not to ask her to dance. In practice, it is Darcy who has the power, not Elizabeth who has been forced to sit out because of the shortage of men. And, as she is known to be a local beauty, we can guess that sitting out is a humiliation she is not used to; Charles. E. Brock’s illustration captures this perfectly.

Beaded reticule, lined with velvet

Fortunately for Catherine in Northanger Abbey, Mr James King, the Bath Master of Ceremonies is there to introduce her to the hero, Mr Tilney. It is part of Mr King’s job to know who has recently arrived in Bath, what their social status is, and to whom it would appropriate to introduce them. We also note that Catherine’s host, Mr Allen, ‘had early in the evening taken pains to know who her partner was, and had been assured of Mr Tilney’s being a clergyman, and of a very respectable family in Gloucestershire.’ Both Mr Allen and Mr King are aware that a young lady’s reputation is at stake.

It is obvious that the rules apply almost solely to ladies and, from a 21st century perspective, they seem to be designed as a way of keeping women in their place. In theory, the rules give ladies the right to decline an introduction but, in reality, this is little more than a sop. The real power remains with the men.

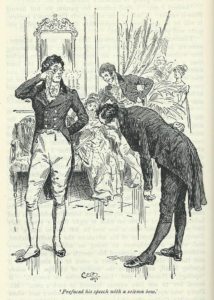

Mr Collins introduces himself to Mr Darcy at the Netherfield Ball

Turning to the rules for gentlemen meeting other gentlemen: ‘The host seldom introduces gentlemen to each other as they address each other as a matter of course.’ We note that considerations of reputation do not apply here. However, rank still matters, as we see in the episode where Mr Collins thrusts himself into Mr Darcy’s notice at the Netherfield Ball.

Elizabeth is horrified, she ‘tried hard to dissuade him from such a scheme, assuring him that Mr Darcy would consider his addressing him without introduction as an impertinent freedom …’ She is only too aware of Darcy’s pride in his rank.

Mr Collins ignores her advice. He insists that, ‘the clerical office as equal in point of dignity as the highest rank in the kingdom – provided that a proper humility of behaviour is at the same time maintained.’ Charles E. Brock’s illustration shows Mr Collins’ obsequious bow.

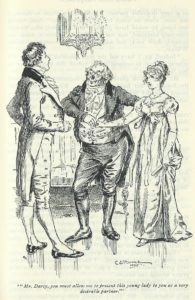

‘Mr Darcy, you must allow me to present this young lady to you as a very desirable partner.’

Later, at the Meryton Assembly, Mr Darcy, now better acquainted with Elizabeth, has discovered, rather against his will, that she is a very attractive woman, and he has no objection to Sir William Lucas wishing to introduce him to Elizabeth as a desirable dance partner.

In Charles E. Brock’s illustration, we can see Elizabeth drawing back slightly as she declines, ‘I have not the least intention of dancing. I entreat you not to suppose that I moved this way in order to beg for a partner.’ It is obvious to the reader that Mr Darcy’s rudeness at the Netherfield Ball still rankles.

Far from being insulted, Mr Darcy approves of her reticence and finds her even more attractive.

The Member of the Aristocracy has yet more advice, this time on introducing ladies to each other. She says, ‘A hostess should always give the lady of higher rank the opportunity of declining the introduction’. If she agrees to it, then the lady of lower rank is introduced to her thus: Miss Sniggs – Lady de Lisle. The first named lady is the one being introduced, making it clear who stands where in the pecking order. For example, when Lady Catherine de Bourgh visits Longbourn, she doesn’t speak directly to Mrs Bennet. Instead, she says to Elizabeth, ‘That lady, I suppose, is your mother?’ As far as Lady Catherine is concerned, there is no introduction and she doesn’t know her.

‘

‘

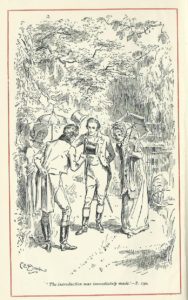

In the grounds at Pemberley. ‘The introduction was immediately made.’ Mr Darcy asks Elizabeth if she will introduce her friends (the Gardiners).

Once we understand the rules, we can fully appreciate the irony of Mr Darcy begging for an introduction to Elizabeth’s aunt and uncle, the Gardiners. Mr Gardiner is in trade, and he is the very person Mr Darcy, in his first proposal, revolted against accepting as an acquaintance. Elizabeth half-expects to see Mr Darcy decamp as fast as possible from ‘such disgraceful companions’. But he doesn’t; instead, he gets on well with them.

Later, Mr Darcy begs to be allowed ‘to introduce my sister to your acquaintance’ . Georgiana outranks Elizabeth, so it should be Elizabeth who is introduced to Georgiana but, by reversing their respective ranks, Darcy lets Elizabeth know just how highly he values her.

Ebony fan with silver sequins

What about those people whom one knew by sight or exchanged a few commonplace words with? Without a formal introduction, it is only a ‘bowing acquaintance’. In Persuasion, Lady Dalrymple spots Captain Wentworth and says to Sir Walter Elliot, ‘A very fine young man indeed! More air than one often sees in Bath. Irish, I daresay.’

Sir Walter replies, ‘No, I just know his name. A bowing acquaintance – Captain Wentworth of the navy. His sister married my tenant in Somersetshire, the Croft who rents Kellynch.’ The reader realizes that Lady Dalrymple’s opinion is important to him and it is not long before the mere ‘bowing acquaintance’ is invited to the Elliots’ At Home.

For a modern reader, these rules can be irksome but they are important in indicating shifts in status or intimacy. And, in my opinion, knowing the rules allows us to appreciate the subtle changes in the relationship between the hero and heroine, and enhances our enjoyment of Jane Austen’s incomparable novels.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

All beautifully observed, thank you. I have that book too. It’s so helpful in many ways.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. I agree about the book being useful. But it’s all so complicated! I would hate to be a Mama in the 1890s paying calls, and having to remember which card to use and whether the corner should be turned down or not; whether or not you should remove your hat; how long to stay (20 mins. max) who you could call on; what you could talk about; how to address a Dowager Duchess, and so on.

Belated congratulations on an interesting post.

Was quite familiar with that portrait of Lord Byron in days of yore.

Susie

Thank you for dropping by, Susie – it’s good to hear from you. I’m delighted that you enjoyed the post. I love that portrait of Lord Byron – it somehow says it all: he’s good-looking, dashing and obviously a hit with the ladies. He may have had a lot of faults but I’ve always liked the fact that he respected Keats and admired his poetry. Others might snootily call Keats the ‘Cockney poet’ because he spoke with a Cockney accent, but that didn’t worry Byron.