In this post, I am remembering the battle of Albuera, on 16th May, 1811 – as I do every year, ever since I visited the battlefield and learnt what happened on that ‘Field of Grief‘ as Lord Byron put it, 208 years ago.

The battle of Albuera in 1811 and the storming of Badajoz in 1812 were among the bloodiest engagements of the Spanish Peninsular War (1808-1813). Almost forgotten today, the battles fought between the British, under Wellington, and their Portuguese and Spanish allies, against the might of the Napoleon’s army were once household names.

The town’s own memorial to the Battle of Albuera

Some of us know Charles Wolfe’s poem, The Burial of Sir John Moore at Corunna beginning, ‘Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note’. Those of us who enjoy Georgette Heyer’s books, will know about Brigade Major Harry Smith’s experience of the Peninsular War and his unconventional marriage to the fourteen-year-old Donna Juana Los Dolores de León after the battle of Badajoz. But generally speaking, the horrors of this most bloody of conflicts have faded almost completely.

Lord Wellington by Robert Home, 1804. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

So what were the British doing in the Iberian Peninsula in the first place? When, in 1808, Napoleon established his brother Joseph as King of Spain, the British army under Lord Wellington seized the excuse of Portugal being Britain’s oldest ally to go to her aid and secure a British foothold in Europe. His army landed near Lisbon.

It took Wellington and his allies five long and bloody years to drive the French back over the Pyrenees, but, in the process, he tied down 300,000 French troops, which, in turn, affected Napoleon’s imperial ambitions in eastern Europe and Russia.

Albuera: looking towards the bridge over the river

In 1811, Badajoz was in French hands and lay, crucially, on the major southern route to Lisbon, essential for Wellington’s supplies and ammunition. He had already failed to take it twice. When he learnt that Maréchal Soult was marching towards Badajoz with 24,000 men, he saw at once that it was a potential disaster and ordered General Beresford to stop Soult at the village of Albuera.

The Fatal Hill, Albuera

Unfortunately, Beresford miscalculated Soult’s probable route and the French took the British and Portuguese forces by surprise. The resulting carnage was appalling: in places, the British forces were outnumbered three to one. Nevertheless, they held their nerve and, after a four hour blood-bath, the French retreated. 4000 Allied soldiers and 7000 French were killed. The battlefield was christened the Fatal Hill. Later, Soult told Napoleon, ‘The day was mine yet they did not know it and would not run.’ A tribute indeed.

When Wellington arrived five days later, it was to find one famous regiment ‘literally lying dead in their ranks as they had stood’. The regiment did not have enough living men to bury the dead.

Lord Byron immortalised the battle in the 1812 narrative poem which made his name: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

O Albuera, glorious field of grief!

As o’er thy plain the pilgrim pricked his steed,

Who could foresee thee, in a space so brief,

A scene where mingling foes should boast, and bleed!

Peace to the perished! May the warrior’s mead

And tears of triumph their reward prolong!

Till others fall where other chieftains lead,

Thy name shall circle round the gaping throng,

And shine in worthless lays, the theme of transient song.

His hero, Childe Harold, visited Spain, just as Byron himself had done back in 1809. The war was in its early stages then and, as Byron noted, it was still possible to travel around. Harold’s adventures in Spain were amorous rather than military but Byron responded to the news of the bloodbath of the battle of Albuera and incorporated it into his poem. Childe Harold was published in 1812, and it’s possible that he included the lines about the battle just before it went to press.

The Chapel of St Joao, Wellington’s military hospital in 1811

In the 19th century, medical provision for those wounded in battle was primitive in the extreme. The nearest military hospital to Albuera was the tiny chapel of S. Joao in the strategically important fortress of Elvas which Wellington used as a base, but it was over twenty miles away. The hospital was woefully inadequate. The doctors did what they could but there were few means of getting the wounded there and scanty medical supplies. If their wounds did not kill them, then gangrene, dysentery and enteric fever probably would.

Albuera: looking towards the French advance. Concealed dips in the ground made it difficult to see the enemy.

We have become used to seeing neat rows of military graves, like the war graves in Northern France from the First World War. In the 19th century, the war dead were stripped naked and buried in huge pits on the battlefield. Their clothes were auctioned off. At Albuera, there were simply not enough men left standing to dig the burial pits deep enough. When Lieut. William Bragge visited the battle site the following year, he noted that the ground was white with bones – the wolves and kites had had their fill.

The ramparts at Badajoz

The situation after the final successful storming of Badajoz the following year was even worse. A surgeon, visiting the main breach the following day, reported: ‘There lay a frightful heap of thirteen to fifteen hundred British soldiers, many dead but still warm, mixed with the desperately wounded, to whom no assistance could yet be given. There lay the burned and blackened corpses of those who had perished by the explosions, stiffening in the gore, body piled upon body…’

Rifleman John Kincaid has another haunting tale from Badajoz. He came across a young officer digging a grave for four of his fallen comrades when ‘an officer of the guards arrived on the spot from a distant division of the army, and demanded tidings of his brother, who was at that moment lying a naked lifeless corpse under his very eyes. The officer had the presence of mind to see that the corpse was not recognized, and, wishing to spare the other’s feelings, told him that his brother was dangerously wounded…’

The British Cemetery at Elvas

In 2000, the Friends of the British Cemetery in Elvas was set up to repair the small neglected war cemetery in a bastion of the fort, together with the tiny adjacent chapel of S. João, once Wellington’s military hospital but which had fallen into serious disrepair. After long negotiations with the Archdiocese of Evora, the Friends were allowed right of usage and took on the responsibility for the chapel’s restoration and maintenance. There are just five marked graves in the cemetery, three from the Peninsular War.

Major General Daniel Hoghton, who was fatally wounded during the battle and died a few hours later, is buried in the cemetery. After his death, his jacket was found to have at least a dozen bullet holes. Hoghton also has a plaque in St Paul’s Cathedral. A stone, laid in 2003, marks the grave of Lieut. Col. Daniel White of the 29th Worcestershire Regiment. Lieut. Col. James Ward Oliver, who served with the 14th Regiment of Portuguese Infantry, also lies in the Elvas Cemetery. And lastly, Major William Nicholas Bull (1801-1850), who served with both Spanish and Portuguese armies in the 1830s is buried there, together with his wife, Caroline.

One corner of the military cemetery, Elvas

According to Charles Oman’s History of the Peninsular War, there may be four other officers who died later from wounds who are also buried there, but their graves are unmarked.

Commemorating the British and Portuguese regiments who fought at Albuera

Nobody knows where the thousands of ordinary soldiers, or indeed, other officers, who died at Albuera and Badajoz are actually buried, but the Friends have placed a line of memorial stones along one wall dedicated to all the regiments that fought at Albuera. Today, it is a peaceful and moving place.

Albuera is immensely proud of its part in that battle and, each May, it hosts a day of commemoration together with the Friends of the British Cemetery in Elvas, to honour those who fought and died there.

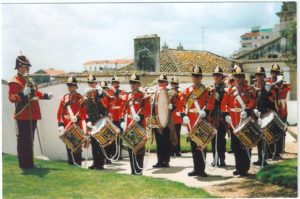

The Corps of Drums, Princess of Wales’ Royal Regiment at the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Albuera, 16th May, 2011

The picture above shows the Corps of Drums – Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, looking splendid in their scarlet uniforms – who took part in the formal ceremony in May 2011 in which the bishop of Evora rededicated the chapel.

Portuguese Infantry Regiment No 8

The picture above shows the Portuguese Infantry Regiment No. 8. They are wearing original 1811 uniforms which were discovered in an old cupboard in the now-disused barracks. Unfortunately, all the uniforms were too small for 21st century Portuguese soldiers, so the ‘soldiers’ in the photograph are, in fact, women.

Sadly, it would take the British Army another 45 years to tackle the inadequacies of the Army medical facilities on another battlefield – the Crimea. Even then it would need the war correspondent for The Times, W.H. Russell’s damning newspaper reports of army incompetence and mismanagement with regard to military supplies and hospital facilities before anything was actually done.

www.british-cemetery-elvas.org

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

What an interesting and touching article, Elizabeth. It is good to know that the sacrifices made in the past by these men are not entirely forgotten.

Thank you for your comment, Penny. I confess to having to swallow a lump in my throat as I wrote it; some of the descriptions of the aftermath of a battle were heartbreaking. Thank God for Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole – even though the army had to wait nearly 50 years for them.

Wow, what a horrifying story. I don’t remember The Spanish Bride well enough to recall this, but it’s tragic how many men died unnecessarily in war at the time, just for lack of medical facilities. A very moving post and the bravery of the troops is heartwarming and poignant.

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. Actually, ‘The Spanish Bride’ opens in 1812, just before the British army tries, for the third time, to take the fortress of Badajoz. The army has just come from Elvas. Juana and he sister are fleeing from the resulting carnage when they meet Harry.

I agree with you that it’s a very poignant story – I felt moved whilst I was writing it and I wanted to do them justice.

I enjoyed reading your post, Elizabeth. I have visited various places associated with the fighting including Elvas and Corunna and found myself quite moved. It’s such a shame that the heroism and sacrifices of the Peninsula War are almost forgotten nowadays: those soldiers were incredibly tough and brave! The Portuguese do seem to remember the conflict rather better. There are lots of memorials and the sites are well looked after.

Lucky you, Gail. I haven’t been to Corunna – though I’ve seen photos of Sir John Moore’s memorial. I’d love to go. Elvas is pretty special, I agree. I suppose it’s reasonable that the Portuguese remember the Peninsular War better than us – it was fought on their soil, after all. I’m sure that bits of bone, bullets, fragments of military equipment etc. must turn pretty frequently in the vineyards around Albuera.