What must it have been like to be held in a prison where the gallows was always visible? Suppose that you had been condemned to hang and would soon be climbing those wooden stairs and feel the hangman put the noose around your neck. The very stones of the place must have smelled of misery and hopelessness – the thoughts jostled through my mind when I visited Downpatrick Gaol, now a museum, in County Down, Northern Ireland.

- The gallows in Downpatrick Gaol

The late 18th century was a period of exceptional violence, both in Ireland, as well as in the rest of Europe and in America. It was also a time of reform and, supposedly, the Age of Enlightenment. There were an increasing number of people, in both America and Ireland, who wanted independence from Britain and were prepared to fight for it.

In March 1798, the Belfast Newsletter announced that the County Grand Jury of Down intended to build a new gaol for the County. It was to follow the recommendations of the great 18th century penal reformer, John Howard, who wanted purpose-built prisons built near the courts they served. They must be well lit and ventilated, with running water and sewerage, and have separate sleeping cells for each prisoner as well as day rooms for different classes of prisoners. This was an innovation, prior to that there was an indiscriminate mix of debtors and criminals, male and female, young and old. Howard also wanted properly paid prison wardens, and for the prison to have its own surgeon or apothecary, and a chaplain with no financial interest in their charges – this was important, the prevailing abuses of the system meant that prisoners were forced to pay if they wanted a single room, or decent food, say.

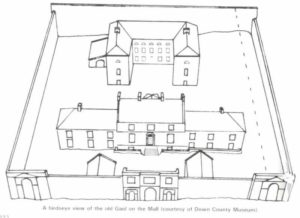

2. Bird’s eye view of the new Downpatrick gaol

County Down obviously agreed and the new Downpatrick gaol opened in 1796. It was hoped that the new building would have none of the overcrowding associated with the old prison system and would be an important tool in the reformation of society. However, the 1790s in Ireland were times of economic and political turmoil and the consequent rise in crime soon led to the gaol becoming overcrowded and increasingly incapable of working efficiently.

Most prisoners were held for very minor offences, for example, petty theft, or being a public nuisance (which could mean practically anything). It was also a convict gaol which held prisoners sentenced to transportation to New South Wales, who often had to wait months, or even several years, before they were actually transported.

3. Downpatrick Gaol. This building housed the prisoners

Thomas Reid, a naval surgeon, wrote a horrific eye-witness account in Travels in Ireland of conditions in Downpatrick Gaol:

‘About ten we arrived in Downpatrick, after breakfast visited the gaol, which is almost as bad as it is possible for a building of that sort to be…. Females of all descriptions, tried and untried, innocent and guilty, debtors and murderers, are all thrown together in one corrupting mass, and kept in a cell not near large enough. Sick or well there they must remain both night and day. There were twenty one thus confined when I saw it, one of whom had been sick for four months; it would not have surprised me had they all been sick….

‘The smell from some of the felon’s cells was intolerably offensive. The prison is insecure; and so wretchedly constructed, that, although room is much wanting, there is one yard of which no use is made; it is covered with weeds and long grass.’

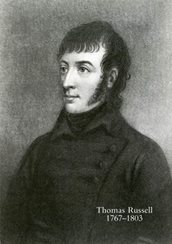

4. The handsome Thomas Russell (1767-1803) Note his fashionable sideburns – a military touch.

It also held prisoners who fought for Irish independence from Britain in the 1798 rebellion, some of whom were hanged on the Downpatrick Gaol gallows. The most notable gallows’ victim was Thomas Russell, friend of the staunch Irish republican, Wolfe Tone. Russell met Tone in Paris during the French Revolution, together with another Irish revolutionary, Robert Emmet. Russell, Tone and Emmet all suffered violent deaths for their beliefs.

I saw the condemned cell in Downpatrick Gaol. It was tiny, dank, dark and had bare stone walls.

Thomas Russell became a local hero in Downpatrick. He was exceptionally tall and handsome; even the warrant for his arrest in 1803 was complimentary, describing him as ‘a tall, handsome man’ of ‘dark complexion, aquiline nose, large black eyes, with heavy eye-brows, good teeth, full-chested, walking generally fast and upright, and having a military appearance … with a clear distinct voice, and … a good address.’

A lot of interesting people visited Paris during the heady early years of the Revolution. I found myself imagining a dinner party in Revolutionary Paris with Thomas Russell, Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet (sure to be interesting on current affairs); the poet William Wordsworth, (a staunch Republican and he had a way with words) the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, (her views on men and marriage could stir things up a bit) and her American lover, Gilbert Imlay (unreliable – but a charmer). It would have made for a stimulating evening.

5. Downpatrick Gaol. The buildings behind the prisoners block

Russell himself comes across as an unworldly man and somewhat naïve. He was convivial, gracious, and thoughtful towards others but he was also deeply religious and introspective and had high moral principles. He was also, alas, the sort of man who found himself constantly in financial distress and he was dependent on the generosity of a number of friends who shared his political views.

He started his career in the army, but that didn’t suit him; several times, he thought of becoming ordained, and later, of trying his fortune in revolutionary France, of which he was a passionate admirer. He was also one of the very few supporters of an independent Ireland with an interest in Gaelic culture, a genuine sympathy for the local people and a supporter of Catholic emancipation..

6. Downpatrick Gaol, the Governor’s House

Together with Wolfe Tone, Russell was one of the founding members of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen. When war broke out between Britain and revolutionary France in February 1793, the Irish authorities clamped down on societies such as the United Irishmen. Russell believed that, with the help of the new Revolutionary France, a Revolution against the British could be successful. In his 1796 pamphlet A Letter to the People of Ireland on the Present Situation of the Country, he openly proclaimed himself one of the United Irishmen, by then a banned seditious organization. He argued that the ordinary people had been betrayed by the Irish gentry who were backed by England, and he championed the cause of the Catholics. The pamphlet was deemed seditious and, in 1796, a warrant was issued for his arrest. He was held until 1802 and then released.

He went to France to try and drum up support for a rising in Ireland against the British – though he distrusted Bonaparte. But the necessary support fizzled away and Russell was captured in September 1803. He was returned to Downpatrick and tried by special commission on 19 October. He high-mindedly refused to offer any defence, but delivered a speech which spoke of his religious feelings, called on the rich to look after the poor, and declared that many gentlemen of the jury had once shared the beliefs for which he was about to die. Russell was executed at Downpatrick Gaol on 21 October.

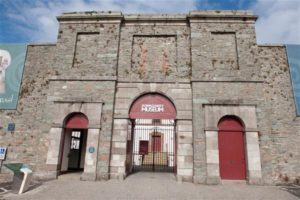

7. The restored entrance to Downpatrick Gaol, now the Museum

Russell’s memory has been kept alive in Downpatrick as a local hero, celebrated in the poem ‘The Man from God Knows where’ by Florence Wilson, which every local schoolchild knows.

It ends thus:

By Downpatrick gaol I was bound to fare

On a day I’ll remember, feth;

For when I came to the prison square

The people were waiting in hundreds there

An’ you wouldn’t hear stir nor breath!

For the sodgers were standing grim an’ tall

Round a scaffold built there foment the wall,

An’ a man stepped out for death!

I was brave and near to the edge of the throng,

Yet I knowed the face again,

An’ I knowed the set and I knowed the walk

An’ the sound of his strange up-country talk

For he spoke out right and plain.

Then he bowed his head to the swinging rope

Whiles I said ‘Please God’ to his dying hope

And ‘Amen’ to his dying prayer

That the wrong would cease and the right prevail

For the man that they hanged at Downpatrick gaol

Was the Man from God knows where.

Conditions in the prison after Thomas Russell’s death continued to deteriorate and the gaol was eventually demolished in 1830, and a new gaol built on a different site. Some of the site buildings became military barracks, and a temporary cholera hospital. The South Down Militia used it during the late nineteenth century. By 1980 what had once been Downpatrick Gaol was almost derelict and a decision was taken to restore the early prison, as far as was possible, to what it had once been and turn the old Dowmpatrick Gaol into a museum to showcase Downpatrick’s rich history (St Patrick is buried just outside the cathedral) and it aimed to attract both children from local schools, and visitors interested in history.

8. Sean Bean in ‘The Frankenstein Chronicles.’

The museum’s Heritage Manager, Mike King, told us how the gallows returned to the museum. In 2015, the director of The Frankenstein Chronicles (starring Sean Bean) asked to film there – and they wanted to build an exact replica of the scaffold and gallows in its original position in the prison yard – and in a state of readiness. With great presence of mind, Mike offered to waive the fee if the museum could keep it once the filming had ended. A lot of secondary school groups visited the museum and he thought they’d love it. He was right.

Gruesome or not, it’s a very visible reminder of the terror such a construction must have once inspired.

Photos: 1, 3 and 5 by Elizabeth Hawksley; 2, 4, 6, and 7 courtesy of Downpatrick Museum; 8, courtesy of Frankenstein Chronicles.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

What a mine of information you are, Elizabeth – who else would tell the world about such a sad, sordid, yet fascinating subject! Poor Thomas Russell, I’m glad his memory is kept green.

Thank you for your comment, Prem. I’m sure that Thomas Russell’s story is better known in Ireland – and rightly so. His death seems to me to have been such a waste. He was a man of undoubted integrity and intelligence but he seemed to have lacked basic horse sense.

Thanks for an interesting post, Elizabeth. My husband’s ancestors were Irish on both sides of his family and several of them were involved in fighting for freedom. One of them was Michael Dwyer who was transported to Australia after evading capture for some months after the 1798 rebellion. He is quite a well known figure – his birthplace is a mini-museum which we visited several years ago – and I wouldn’t be surprised if he knew Thomas Russell.

How fascinating, Gail. I’m sure that most of the rebels knew each other, or at least had heard of each other. Thomas Russell seems to have got about quite a bit: he wasn’t known as ‘The Man from God Knows Where’ for nothing!

It doesn’t seem as if the new gaol was any better than the old one! I’ve read up about these old institutions too since they figure occasionally in my mysteries. They were pretty grim. One of the best descriptions for me comes in Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge. I didn’t think I’d enjoy it, but it turned out to be a fascinating piece of history (the Gordon riots) and very much in Dickens’ dramatic style, though convoluted. But there’s much about prisons, which was both interesting and useful for me.

I have to say that having the gallows in the corner all the time is pretty heinous. But they were a barbaric lot in the 18th Century, no getting away from that.

Thank you for your interesting comment, Elizabeth. The gallows, as you can see from the photo, is pretty large. You couldn’t take it down in between hangings. I suppose they regarded its presence as a deterrent.

I think the main problem was there there were far too many petty crimes which were seen to warrant gaol, many of which were caused by the wretched poverty most ordinary people had to live in.

Isn’t it interesting how a seemingly unimportant place like Downpatrick can be a nexus for the telling of so many intertwined stories?

So much suffering must have been endured within those for walls. It’s good to be reminded periodically of how fortunate we are in comparison to those poor souls.

I wonder how history might have been different if Thomas Russell had been punished by being sent to the colonies instead of being sent to the end of the noose.

Thank you for your comment, Huon, but I must take issue with you about the ‘seeming unimportance’ of Downpatrick. I assure you that, in Ireland, Downpatrick is well known. It is the County town of Co. Down, and St Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, is buried just outside Downpatrick Cathedral!

But you are quite right about the importance of remembering just how awful prison life – and death – could be 200 years ago. It would indeed have been interesting if Thomas Russell had been sent to Australia – which, after Britain lost America, was the colony of choice for transportation – I think that he might well have become well known, in a good way.