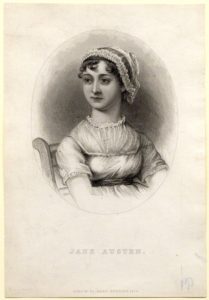

In 2013, Joanna Trollope published Sense & Sensibility, one of the Austen Project books which aimed to re-write Jane Austen’s novels, scene by scene, but in a modern setting. I have only just read it, and I can’t understand how I came to miss it – perhaps because 2013 wasn’t a good year for me. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and she has an interesting take on Margaret Dashwood.

Continue reading Jane Austen: Part II, Margaret Dashwood and ‘Sense & Sensability’

Please share this page...