My copy of this famous book belonged to my grandfather and dates from the late 19th century. It’s based on a French translation by Antoine Galland, who heard it in oral form from a Middle Eastern story teller in Aleppo, sometime in the early 17th century. Galland’s translation appeared in 1704-8 and became an instant hit. James Mason, who edited this English version, wrote: ‘Few works have been translated into so many languages, or given such wide-spread delight.’

He felt that it was particularly well adapted ‘for putting into the hands of the young, to stimulate their growing faculties, to cultivate their imagination, and to assist, by healthy exercise, the expansion of their mental powers.’ We know that Charles Dickens loved the stories since childhood. As my grandfather’s copy was acquired when he was well into his forties, I would argue that it’s a wonderful book for all ages.

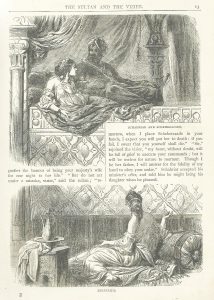

The Sultan Schahriah and Scheherazade (above) and her sister Dinarzade (below)

I do not know who is responsible for the illustrations; the frontispiece says only ‘With numerous illustrations.’

We all know the story of the sultan whose wife betrayed him and who, thereafter, decided that all women were faithless and that, although he would take a new wife every day, he would have her killed the following morning by his vizier. So when the vizier’s elder daughter, Scheherazade, declared that she was willing to marry the sultan, he refused his permission. Eventually, he gave way. Scheherazade devised a plan; in the morning, her sister, Dinarzade, would beg her for a last story. Scheherazade would tell the story (with the sultan listening) – but she stopped at a cliff-hanger. The sultan allowed her to live one more day to complete the story.

The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments is a series of stories within stories, each one stopping at a crucial point, while another story took over.

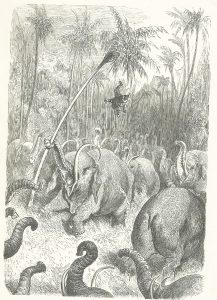

Sinbad and the elephants

One of the most famous is the story of Sinbad the Sailor and his seven voyages. Every conceivable adventure befalls him: the dramatic illustration shows an elephant uprooting the tree in which Sinbad is hiding (he has been shooting them for their ivory) whilst the other furious elephants mill around, expressing their displeasure.

As the Scheherazade’s stories go on, it’s impossible not to detect traces of Greek legends stories as if somewhere, lost in the mists of time, there are legends of huge birds, like the Roc; or cannibal giants, like Polyphemus; who have common ancestors.

The Enchanted Horse whose possession allowed a villain to abduct a princess of Bengal, and, later, enabled her lover, Prince Firouz Schah, to rescue her.

I particularly like the flying horse, which reminds me of Pegasus, the Greek god Apollo’s flying horse whom Perseus rode when he rescued Andromeda from the dragon. There are flying horses in legends from across the world. For example, Helios, the Greek sun god, drove the horses of the chariot of the sun every day from east to west; and there are flying horses in Scandinavian legends as well.

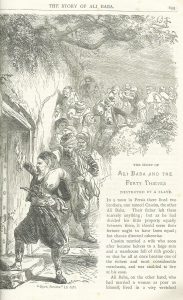

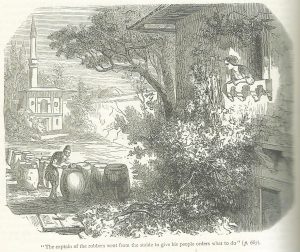

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves; the bandit chief shouts ‘Open, Sesame’ to open the door to the cave of treasure.

Another favourite story is that of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and I love this illustration. I like the way the bandits come in a great rush down the stairs and the story starts in the bottom right hand corner. The bandit chief, bristling with weapons and arm upraised, is a striking figure.

The bandits hiding in the jars, whilst Morgiana watches secretly

The second Ali Baba illustration shows the jars of oil – forty of which hold the hiding robbers, the others hold oil. The bandit chief leans over one of the jars, reminding the occupant what the robbery plan is. Unseen by him, the clever and brave slave girl, Morgiana, is listening.

I like the way that there are a number of courageous and resourceful women in The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments’, like Scheherazade herself.

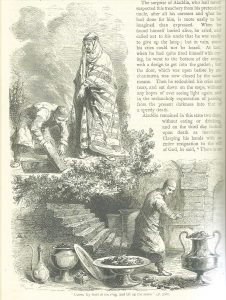

Aladdin, or The Wonderful Lamp

This is another illustration where the words and picture mingle. It’s also a sort of comic strip. At the top left, we see Aladdin’s supposed uncle getting him to open the trap door to the place where the treasure is hidden. We see the stairs going down. Then we see Aladdin again, this time inside the cavern, amazed by the treasure it contains. But he hasn’t come down for treasure, he’s come for the magic lamp which his uncle wants.

Little does he know that his uncle plans to lock him inside the cavern….

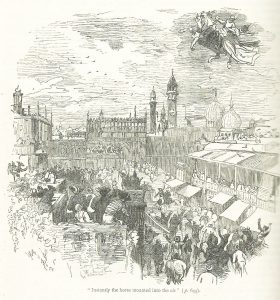

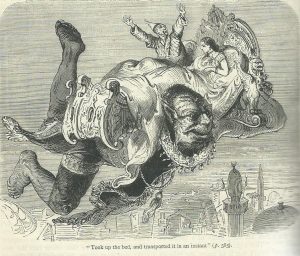

The genie, at Aladdin’s behest, transports the Princess Badroulboudour and the Vizier’s son back to the palace.

The genie, who is horrible to behold, is visible only to Aladdin. I like the ornate sleigh bed the genie is carrying and the way we look down on domes and minarets.

I’ve always enjoyed the Arabian Nights’ tales; I love their endless inventiveness; the surprising things that happen, the way that right triumphs – eventually, but not without a lot of adventures and the testing of mettle first; and I note that, although the women are definitely second, if not third class citizens, nevertheless, they, too, are admired for their cleverness, cunning and bravery as well as their beauty.

It’s no wonder that writers, composers, artists, choreographers and film makers have constantly sort inspiration from these wonderful stories.

Elizabeth Hawksley

Please share this page...

Fabulous illustrations! I have the Richard Francis Burton trans. – in a three volume edition from the 1930s. Lavish boards cover the tomes, but it’s mostly text inside and the illustrations are quite flat compared to yours. Haven’t read these – yet. Have you read the Burton? That is to say, can you offer a comparison betwixt the Galland and the later translation? I have heard the Burton was considered a bit, um, blue back in its day. Is the Galland similarly ribald?

Thank you for your comment, Steve. According to the editor of my version: ‘Many passages in the old versions were extremely objectionable in point of taste and propriety; these have been either altered or expunged.’ I think this answers your question!

If you want to know more about my individual books, please click on any book in the Books page

I had a copy of these tales, in a selection for children from the 1920’s, given to me by MY grandfather. It had full plate colour illustrations, including one of the flying trunk, as well as a terrifying afrit emerging from the bottle and a cover embossed with an extremely corpulent pasha. Sadly, while on sabbatical I rented out our house and this volume had disappeared by the time we returned so I can no longer remember who the illustrator was. I think that the major source of the stories was Persia but there is more than one tributary stream in this rich river of stories.

I’ve dipped into the Sir Richard Burton version and he affects a rather off-putting archaic diction but that might well mirror the story-telling conventions of the Arabic originals.

Thank you for your interesting comments, Pauline. Lucky you, having had a copy of The Arabian Nights with full colour illustrations – they sound fantastic. I’m sure you are right about Burton’s archaic language. The Eastern story-telling tradition does depend on flowery language – it’s there to heighten the emotion.

What wonderful illustrations! I love the Arabian Nights, and as you say, a rich source of all sorts of productions. The racy original stories are available these days, I know. My father gave one set to my nephew, who is an art director for film and TV. What is it with grandfathers and The Arabian Nights, I wonder?

Thank you for your comment, Elizabeth. What is it with grandfathers and The Arabian Nights? Beautiful and intelligent women who do as they are told?